Share post now

global

The Alliance Sud magazine analyses and comments on Switzerland's foreign and development policies. "global" is published four times a year (in german and french) and can be subscribed to free of charge.

Article, Global

27.06.2023,

The next crisis is as certain as the fact that tomorrow a tram will stop at Paradeplatz, the heart of Switzerland‘s financial sector. What no one knows is just when and from where it will originate in the gigantic and complex financial system.

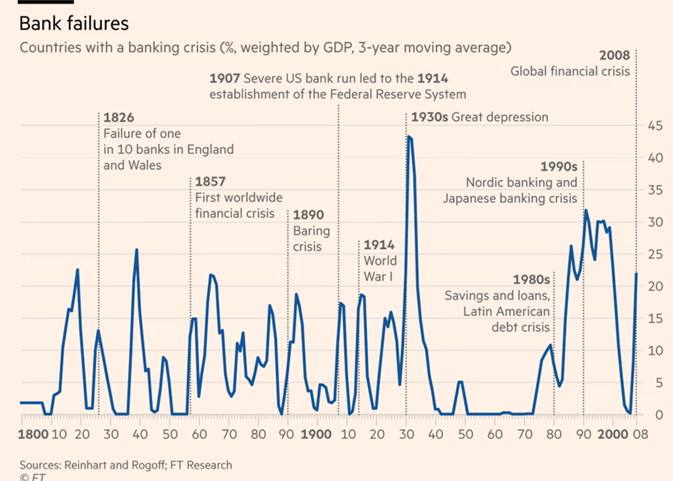

© Reinhart and Rogoff; FT Research

The past 200 years have witnessed just one period that was free of any major financial crisis – from 1945 to 1973. Why was this? During the "Trente Glorieuses", as the 30-year post-war boom is called in France, there was stricter regulation of banks and the import and export of capital, and currencies were not freely convertible. It was also a time with virtually no bank failures, as shown by the chart that follows.

And what is the source of the prediction that, in the wake of the collapse of Credit Suisse into the embrace of UBS, the current crisis is still not over also in Europe? It comes from history, which tells us that many major financial crises in the USA came on the back of sharp interest-rate increases there.

Higher central bank interest rates shift the entire price structure in financial markets. Government bonds issued during periods of low interest rates yield only low returns over their entire lifetime – which may be several decades – owing to the low interest rate. New bond issues, in contrast, have a higher interest rate, which depresses the prices of low-interest bonds, and by extension their value. Financial houses that must value or even dispose of old bonds in their portfolios at current prices, do have a problem.

Rising interest rates are also perilous because borrowing has been so cheap in recent years. The financial market therefore became inflated. In the period from the massive 2008 financial crisis until 2021, the volume of global financial assets more than doubled, while global Gross Domestic Product (GDP) grew by only a third. The upshot is that the financial market is currently more than five-and-a-half times the volume of total worldwide goods and services output (i.e., global GDP).

The low interest rates made it possible to "leverage" yields and, in very simplistic terms, it worked as follows: a hedge fund (an unregulated investment vehicle mainly for very rich clients) has an investment opportunity with a 5-per cent yield. It invests 100 million and makes a profit of 5 million, which it nonetheless considers vastly insufficient. It therefore borrows 1000 million from the banks at 2-per cent interest, which it then invests at a 5-per cent yield. With the 3-per cent interest differential, it garners a further profit of 30 million. The overall return is now 35 million rather than 5 (it must pay the bank 20 million in interest, but at the same time earns 50 million from the reinvested loan – with a difference of 30 in its favour). This – again in grossly oversimplified terms – is the reason why the biggest fortunes have grown exponentially over recent years.

Yet another outcome of low interest rates is that business models or companies that in "normal" circumstances would have gone bankrupt, are able to survive. Even the US Federal Reserve refers to such companies, which in fact are no longer profitable, as "zombie companies". Riskier corporate bonds are "particularly vulnerable" to interest-rate hikes, and "heightened geopolitical risks increase the likelihood of financial vulnerabilities crystallising", warned the Bank of England in late March in its usual carefully couched institutional language. Also regarded as especially risky at present is Commercial Real Estate (CRE), which comprises business properties, mainly in the USA. Besides the fact that cheap money led to overbuilding, there is now also uncertainty as to whether office buildings will all still be needed in an age when more people are working from home.

So, a few companies and real estate funds may well go bust – but who cares? The fact that market analysts and regulatory bodies are addressing the matter is down to mechanisms well-known from the 2008 global financial crisis. CRE debt is not simply held by a few US regional banks (of which some are already teetering precariously on the brink, or have already failed). It was also blended together and packaged into derivatives, i.e., second-tier financial assets that serve as their underlying asset. These were then packaged into "risk tranches" and sold on. It is therefore not clear who is sitting on bad loans and which financial institutions have given credit to those sitting on potential bad loans. The sausage analogy is the best way to visualise this. If one ingredient consisted of rotten meat, you no longer look at individual slices of the sausage to see whether it is affected, but avoid the whole sausage altogether. The last global financial crisis in 2007/2008 triggered such a domino effect, which began with private mortgages. By the end of the crisis, distrust was so rife in financial markets, that banks stopped lending to one another. That could well happen again now.

The role of shadow banks has grown disproportionately since 2008 and, according to the Financial Stability Board, they now make up more than half of the global financial system. They comprise hedge funds, private equity firms and institutional investors that admittedly do some of the same things as banks, though without being regulated and supervised in the same way. They do indeed stay in the shadows and most are resident in tax havens. To calm things down, regulatory authorities no longer speak of the shadow banking system, but of Non-Banking Financial Institutions (NBFIs). NBFIs, however, remain untransparent and opaque; hedge funds, for instance, speculate with their own funds and with large amounts of borrowed funds on everything that moves and promises any kind of return - from falling equity prices, to corporate bankruptcies, to the weather (yes, there are weather derivatives). Private equity funds invest in venture companies and bankroll corporate takeovers. Shadow banks also include financing and investment companies like BlackRock, index funds, money market funds, or "family offices" of the super-rich. Pension funds and insurance groups also use shadow banking.

It is not the case, however, that shadow banks, on the one hand, operate side-by-side with the universally known banking houses on the other; instead, the two are intertwined in many ways through debt and investments. And many players in the shadows, e.g., certain hedge funds, are particularly highly indebted. This is why the shadow banking system is regarded as the first domino likely to fall.

And what does this currently mean for Switzerland? According to the financial markets oversight body, Finma, the new UBS now holds 35,000 billion francs in derivatives and structured products. Martin Wolf, chief economics commentator of the Financial Times and author of a standard work on the global financial crisis, tells the "NZZ am Sonntag": "It is extremely unlikely that management understands the risks facing their bank, regardless of what they say. The situation is also really complex, there are claims against so many counterparties about which not much is known (...)." And he concludes: "If I were Swiss, I would be saying to myself: this new cuckoo, the UBS, is perhaps slightly too big for our nest."

Share post now

global

The Alliance Sud magazine analyses and comments on Switzerland's foreign and development policies. "global" is published four times a year (in german and french) and can be subscribed to free of charge.