Share post now

Investigation

Switzerland in the dense fog of carbon offsetting

20.11.2024, Climate justice

With the purchase of new cookstoves, Ghana is expected to save more than 3 million tonnes of carbon emissions, thanks mainly to women – as a substitute for emission mitigation in Switzerland. Alliance Sud criticises the project's glaring lack of transparency and highlights controversial details that project owners attempted to hide from public view.

A girl cooks with her mother in her home in Tinguri, Ghana.

© Keystone / Robert Harding / Ben Langdon Photography

Grace Adongo, a farmer from Ghana's Ashanti region, is happy with her new and more efficient cookstove. Instead of cooking on an open fire, she now places the pot on a small stove. She needs appreciably less charcoal, which both saves money and mitigates carbon emissions. This testimonial comes from the latest Annual Report of the Ghana Carbon Market Office and coincides with many others that are reporting on the numerous cookstove projects throughout the global carbon market. These projects supposedly help provide poorer population groups with cookstoves that are more efficient and less harmful to health than traditional stoves or fireplaces, which generate large amounts of smoke. This reduces wood consumption and carbon dioxide emissions (how much is highly controversial – but more on that later).

The principle involved is always similar. The cookstoves are sold cheaply. This entails customers transferring to project owners their rights to the emission mitigation outcomes. The emissions saved by the new stoves are then calculated over the ensuing years and sold internationally by the project owner as carbon certificates. The proceeds from the certificates are needed to subsidise the cookstoves.

From the personal standpoint of people like Mrs. Adongo, what sounds like a good thing is also precisely that. But the system as a whole is much more multilayered and contradictory. The case mentioned at the start, the Transformative Cookstove Activity in Rural Ghana, which Alliance Sud examines in detail in this paper, revolves around the government carbon offset market in which Switzerland imputes the emission mitigation outcomes achieved in Ghana to its own climate goals. A surprising number of venues also come to light in the process, and also warrant critical assessment from the standpoint of climate justice. Switzerland's cooperation with Ghana is also a good example of why the trade in certificates under the Paris Agreement is not conducive to attaining the ambitious climate goals.

Carbon certificates from this and many other projects are being paid for with a 5-centime tax assessed on each litre of fuel at Swiss petrol pumps. Owned by motor fuel importers, the Foundation for Climate Protection and Carbon Offset KliK provides the money for mitigation projects in Switzerland and abroad. Through carbon offsetting abroad, Swiss lawmakers aim to compensate for climate mitigation actions not taken in Switzerland, so that they are still able to meet the climate goals of the Paris Agreement.

Under the 2015 Paris Agreement, Switzerland undertook to halve, by 2030, its greenhouse gas emissions compared to 1990. With the CO2 Act, however, only about 30% of emissions can be mitigated in Switzerland – barely more than before the law was revised in the spring of 2024. The remaining 20% must be offset abroad. Under the Federal Council's savings package announced in September 2024, climate mitigation activities in Switzerland are also expected to diminish. The inevitable consequence is that Switzerland will need more carbon offset certificates if it is still to achieve the climate goals. That is not the meaning of Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, under which the transfer of emission mitigation outcomes to other countries should lead expressly to "higher ambitions". To achieve this, Switzerland will have to ensure that the climate goals of both countries are consistent with the goals of the Paris Agreement. Switzerland has promised net zero by 2050. Because net zero is to be achieved globally by that same year, Switzerland therefore expects other countries also to set their net zero target at 2050. Measured against this yardstick, there are substantial gaps in Ghana's national contribution, up to 2030, towards the realisation of the Paris Agreement. Ghana has announced only a non-binding net zero target for 2060 and excludes oil production from its climate goals. When contacted in that regard, the Federal Office for the Environment (FOEN) writes: "The requirements of the Paris Agreement apply", and points towards the unilaterally set climate goals based on the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capacities. "In the process, climate goals must encompass the highest possible ambition and subsequent goals must be even more ambitious." However, there are no other criteria for the climate goals of a partner country.

A year ago, Ghana announced the expansion of oil production, adducing the lack of financial support for climate protection as the reason. This illustrates the fundamental problem: the countries in the Global South lack the international climate finance that should be forthcoming from the Global North by way of support. The upshot is that they opt for what they see as their second-best solution for raising funds, that of selling the outcomes of their climate mitigation activities as carbon certificates. The difference with climate finance is that Switzerland obtains the "right" to postpone its climate mitigation measures. On balance, ambitions for effective climate mitigation are being lowered, not raised.

Dense fog in February

Ghana and Switzerland approved this cookstove project in February 2024 under the bilateral market mechanism of the Paris Agreement (Art. 6.2). It is being implemented by the Amsterdam-based company ACT Commodities (project owner, see Box 2) and is projected to record a 3-million tonne reduction in carbon emissions by 2030. It is therefore incumbent on both governments to ensure that the project fulfils and maintains high quality requirements, which it promises to do. The Federal Office for the Environment (FOEN) verifies the relevant project documentation and publishes them upon authorization.

The project owner is ACT Commodities, an international conglomerate headquartered in Amsterdam. On its website, the company describes itself as the leading global provider of market-based sustainability solutions that is driving the transition to a sustainable world. ACT is a major player in emissions trading. But the company prefers to avoid too much transparency – its own website fails to mention that the conglomerate also has oil and fuel trading in its portfolio (through its sister company ACT Fuels, which has no website). This comes to light thanks only to a perusal of the Dutch commercial register. Since July 2023, ACT Commodities has also owned a company that supplies marine fuels, the dirtiest of all fuels. The conglomerate is therefore one of a growing group of commodity traders doing business with fossil fuels and simultaneously "greenwashing" themselves as players on the carbon market.

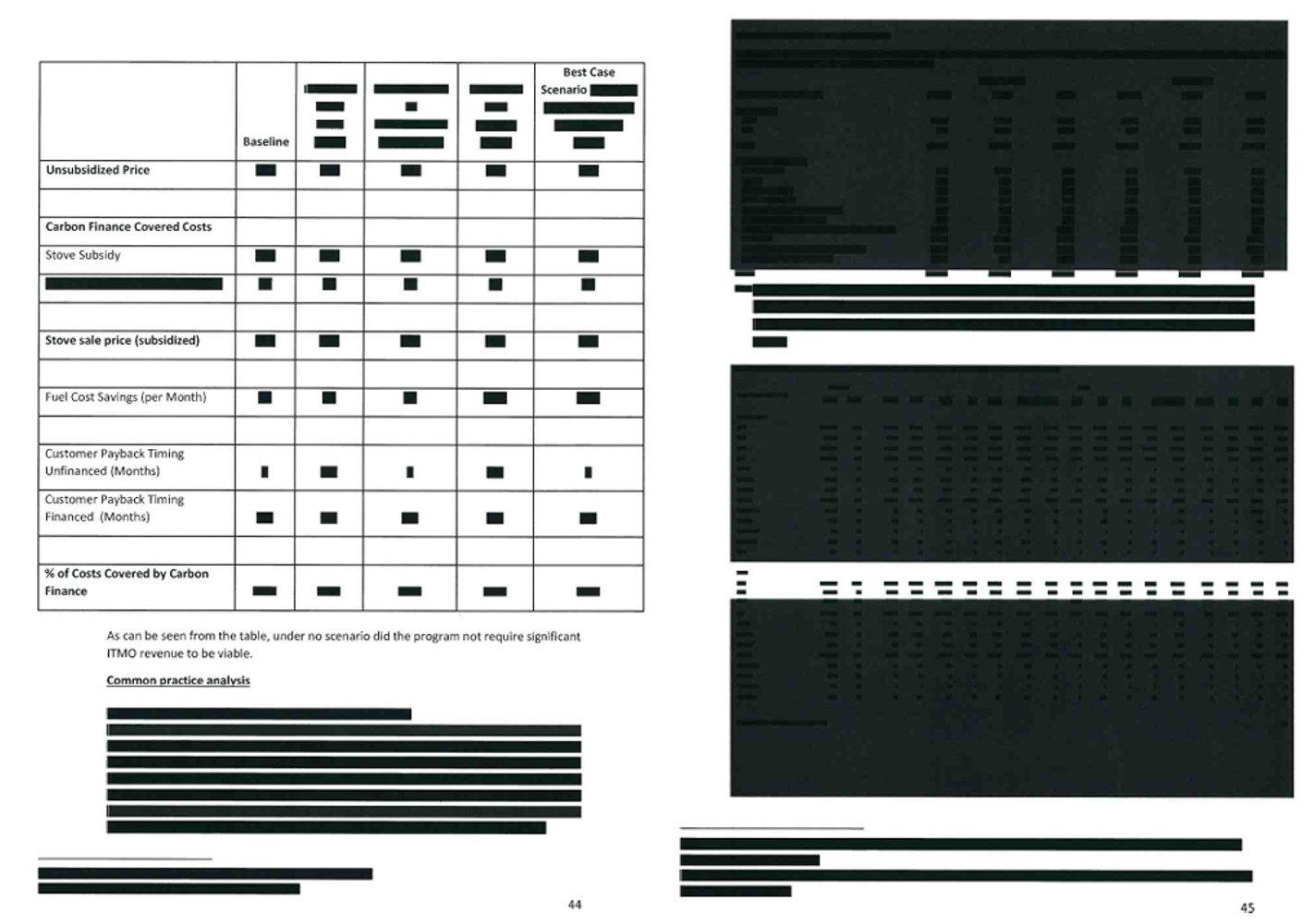

But the very first look at the documents reveals a lack of transparency: the project is as opaque as dense fog. Extensive passages in the project description are redacted, including virtually the entire analysis that is meant to prove that the project will lead to additional emission mitigation (see chart). But many other relevant facts and figures were also concealed. And the document containing the calculations showing why the CO2 reduction should amount to 3.2 million tonnes was not even published in the first place. That is not what transparency looks like.

Alliance Sud requested publication of the unredacted documents and calculations pursuant to the Freedom of Information Act (FoIA) – and had to wait four months owing to the project owner's initial refusal. Much, though not all of the project documentation was released thereafter. The passages that were still redacted were supposedly business secrets. It is now also becoming clear that in the original document, many places had simply been arbitrarily concealed.

Excerpt from the analysis of the project's additionality, originally redacted altogether.

Emission mitigation is being overestimated by up to 79%

The calculation methodology whereby the project in Ghana is expected to save 400,000 tons of carbon emissions annually over eight years is a key piece of information regarding carbon offset projects. Reputable certifiers in the voluntary carbon market require project owners to disclose these calculations. These data must be made available for scientific analysis – especially since a growing number of studies are identifying cases of over-crediting of emission mitigation through carbon certificates, including for cookstove projects.

In this case, however, the project owner is reluctant to do so – an unacceptable lack of transparency. Alliance Sud submitted an FoIA request and obtained a PDF copy of the calculation tables. Without being able to view the integrated Excel formulas, verifiability remains limited.

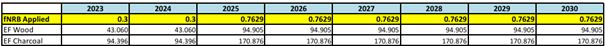

But the figures now available offer surprising revelations. The PDF document containing the calculations shows that for the years 2025-30, emission reductions for the same stoves are being calculated at almost twice as much as for the years 2023-24. The underlying reason is obviously a planned increase of the most key metric, namely, the fraction of non-renewable biomass (fNRB). This is an estimate of the amount of wood biomass by which the harvesting of fuelwood exceeds its natural rate of regeneration. Only reduced use of non-renewable fuelwood can be regarded as a reduction in carbon emissions. The metric is multiplied directly by the other factors and is therefore crucial to calculating emission mitigation. The overstating of the fraction of non-renewable biomass (fNRB) is the main reason for the sometimes-scathing criticism elicited by cookstove projects launched to date for emission mitigation purposes.

For anyone keen on the details, the project documentation showed an fNRB set at 0.3, which is more conservative than for many previous cookstove projects. According to the official UNFCCC reference study dated June 2024, this is an appropriate standard value, as it avoids massively overstating emission mitigation and is also consistent with the country-specific value contained in the study for Ghana, which is 0.33. However, the project now has a clause enabling Ghana and Switzerland bilaterally to adjust the fNRB retrospectively (upwards). The fact that concrete calculations are already being done, from 2025 onwards, on the basis of an fNRB of 0.7629 only comes to light from the PDF document containing the calculations, which was not originally published. The project description fails to mention that plans are already being laid using a higher value, even though it is still to be validated. The value 0.7629 comes from the outdated "CDM tool 30" which is deemed by the FOEN itself to be insufficient as a basis. In the spring of 2024, Ghana invited tenders for an independent study to determine a country-specific fNRB value for Ghana – obviously in the hope that a markedly higher value can be validated. If Switzerland is also to accept it, the study must pass the peer review by UNFCCC bodies. In the light of the aforementioned widely accepted reference study which calculates a country value of 0.33 for Ghana, that is likely to be an uphill task.

A look at the calculation document shows that as of 2025, calculations are to be based on an fNRB – the most important metric – more than two times higher (line in yellow). According to Alliance Sud calculations, this means that between 2025 and 2030, emission mitigation will be overestimated by up to 92%. All told, the overestimation is up to 79% (using the correct calculation for 2023 and 2024).

If a baseline fNRB value more than twice as high is applied, with no basis whatsoever, emission mitigation is being overestimated from the outset. According to Alliance Sud calculations, the project would reduce carbon emissions by 1.8 million tonnes at the most, if the fNRB value is held constant at the more realistic level of 0.3. But the project promises a reduction of 3.2 million tonnes of carbon emissions. It thus overestimates overall mitigation by up to 79%.

Some research lifts the fog…

The absurdity of attempting to describe half of the project documentation as "business secrets" (in the first version of February) is clear from the fact that much of the concealed information is publicly available in other places. If few more minor items of information that had originally been concealed are even available elsewhere in the same document. Further information can be gleaned from Ghanaian Government documents, or can be deduced from other sources.

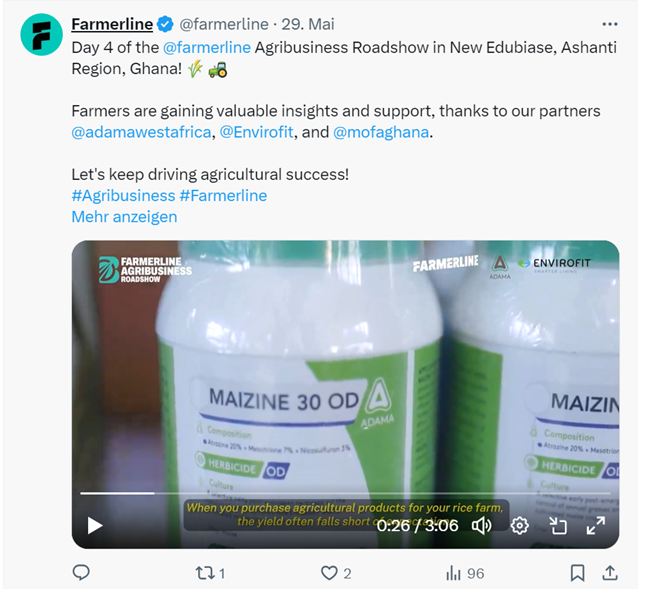

For example, from an online article by the Ghanaian authorities about a visit by the KliK Board of Directors, we learn who is the project's main distributing partner in Ghana – a Ghanaian company called "Farmerline". Farmerline facilitates access for farmers to agricultural inputs, thereby opening up the global agricultural industry to many new clients from Ghana. The project owner also attempted to conceal this connection. Several references to partnerships in the agriculture sector had originally been hidden in the project documentation, and specific cooperation is still redacted. There are reasons, as a closer look will show.

...lingering pesticide spray

In June 2023, Farmerline announced its cooperation with Envirofit, the cookstove producer and the project owner's implementing partner. The project documentation also describes plans to sell 180,000 stoves to rural dwellers within a short space of time, and notes that the stoves will be available at more than 400 businesses for agricultural inputs. But some posts by Farmerline on the "X" platform do arrest the attention of readers. This year, Farmerline conducted an "Agribusiness roadshow" across various regions of Ghana in cooperation with Envirofit – and with the crop protection company Adama, a member of the Syngenta Group. On each day of the roadshow, farmers were presented with the efficient Envirofit cookstoves and Adama pesticides, both being put up for sale. Adama products are identifiable in the Farmerline videos, including three insecticides and one herbicide containing active substances banned in Switzerland and the EU because of their toxicity to the environment and human health. They are atrazine, diazinon, and bifenthrin. Atrazine pollutes groundwater, hampers photosynthesis in plants and is virtually impossible to remove from the environment; it is also classified as a carcinogen. Diazinon attacks not only the pests being targeted but all insects and can also be highly toxic to humans if it comes into contact with the skin. Bifenthrin poses a danger mainly to aquatic animals but should also not be inhaled by humans (see the Pesticide database maintained by Pesticide Action Network).

Sample photo from a Farmerline roadshow video in which the herbicide Maizine 30 OD containing the active substance atrazine – banned in Europe – is also being sold alongside cookstoves.

Furthermore, none of the videos contains a demonstration or the sale of appropriate protective clothing. According to various studies (Demi und Sicchia 2021; Boateng et al 2022; and others), the growing use of pesticides in Ghanaian agriculture is leading to considerable health problems for farmers. In the absence of instructions from dealers, many either do not know how to use the pesticides properly and protect themselves in the process, or they lack sufficient funds to be able to afford protective clothing. Besides, they obtain expert information mostly from their personal circles or from some dealers, but no independent agricultural advice is available. In their study, Imoro et al. 2019 found that 50% used no protective clothing at all and another 40% were not sufficiently protected. Asked whether protective clothing was also being sold at the roadshows, KliK replied that the highest standards of sustainability were of course a prerequisite for their cooperation partners. KliK writes that the issues raised by Alliance Sud with this question lie outside the scope of its discretion.

Thus, attempting to obtain a clear statement regarding the benefits of this offset project for sustainable development is still akin to stumbling around in the dark. Cookstove customers will indeed save money and, as there is less smoke, also hopefully improve their health. Yet, they are simultaneously being urged to spend the money saved on pesticides, the increased use of which is damaging the environment and also creating new health problems in many instances. From this perspective, KliK's assessment of its cooperation partners' "highest standards of sustainability" is erroneous. It is indeed reasonable to strive for synergies with existing players in the agriculture sector in order to reach rural dwellers. But had sustainability been the uppermost concern, a partnership with organisations that promote agroecological approaches would much more likely have suggested itself.

Eye-watering profits for investors

While the new cookstoves enable customers to make financial savings, the project is financially worthwhile for the investors on a much larger scale. It lacks transparency also from a financial standpoint in that the pricing of the stoves is redacted, and the prices of the certificates are a private matter for KliK and its business partners. Moreover, the FOEN is not reviewing a financial plan or anything similar for the project. Yet, from the additional information released following the FoIA request, it is clear that investors are likely to rake in handsome profits. The investors behind this project are invisible, but according to project documentation, can expect an annual return of 19.75% on their investment. A comparison is being drawn with Ghanaian government bonds in order to justify this absurd return. That comparison holds no water whatsoever, as the one thing has nothing to do with the other. The risks associated with investing in a government bond issued by an already highly indebted country are of an entirely different nature – which accounts for the high yields (although it does not legitimise them, as the high interest rates for poor countries are horrific and catastrophic – but again, that is another story).

What this case involves, in contrast, is a project partly financed and secured with quasi-public funds; this could be classified as blended finance, a mix of public and private financing. This is so because fuel importers collect a levy on fuel, by virtue of the CO2 Act. At a purely technical level, should the proceeds of this levy pass through government coffers – as other levies generally do – before being disbursed for carbon offset projects, that would make them taxpayers' money.

That would give rise to a public interest in ensuring that the proceeds from this levy are used efficiently. The funds must go towards climate mitigation and sustainable development in the country concerned, not towards gold-plated returns for investors.

Conclusion

Efficient cookstoves are an inexpensive way of improving the lives of many people while mitigating greenhouse gas emissions. Yet, there are considerable contradictions lurking in the market mechanism under the Paris Agreement when implementing climate mitigation projects in the Global South. It is meant to promote sustainable development locally, but is conceived as potentially lucrative business for investors. And while some emissions are being reduced in the Global South, the mechanism offers a political pretext for postponing climate mitigation activities in a country as rich as Switzerland.

Transparency in the certificate trade is therefore the key to discovering the multilayered and potentially problematic background to carbon offset projects. Switzerland's carbon mitigation project in Ghana is a telling example of this. Neither the overestimation of emission mitigation, the sale of toxic pesticides nor the exorbitant yields could be gleaned from the documents that were published following the authorization of the cookstove project. It was only through an FoIA request and further investigation that Alliance Sud was able to clear the fog of non-transparency shrouding the project documentation: what came to light was the approval of reckless calculation methods, business practices by implementing partners inimical to the environment and to people, and a questionable interpretation of transparency by the main players. However, the possibility of public scrutiny remains crucial to ensuring that carbon mitigation projects do not endanger implementation of the Paris Agreement.

This case is the second carbon offset project by Switzerland under the Paris Agreement to be looked into by Alliance Sud. A year ago, Alliance Sud and Fastenaktion elucidated the reasons why new E-buses in Bangkok are no substitute for climate mitigation activities in Switzerland.

Climate and Taxes

A duo on a world tour

04.10.2024, Climate justice, Finance and tax policy

Without the polluter-pays principle, international climate policy cannot be funded – without tax justice, it is not feasible. A mini-world tour with an unequal but perhaps soon symbiotic duo.

More and more activists and multilateral forums around the world are linking demands for tax and climate justice. Protesters at the Fridays for Future parade in Berlin, 20 September 2024. © Keystone / EPA / Clemens Bilan

It is really immediately clear – to be able to afford transitioning away from fossil fuels without major social dislocations, we must raise the requisite funds from those industries that were the first to enrich themselves from them, namely, the fossil fuels industry. Studies show that more than half of all worldwide emissions since 1988 can be attributed to the exploitation of fossil fuels by just 25 companies. No one has ever paid up for the long-term costs being engendered by these emissions, which are causing climate change. At the same time, the profits and dividends accruing to those trading in these fuels have risen continuously. Thanks to the price increases triggered by Russia's invasion of Ukraine, the 2022 profits of oil and gas companies skyrocketed to four trillion dollars

Make polluters pay

It is therefore no surprise that in the context of the urgent need for climate funding for the Global South, and in keeping with the polluter pays principle, the call is growing louder for additional taxation of these companies. This goal has long been present in international civil society under the slogan "Make polluters pay". A current study by the Heinrich Böll Foundation shows that in this very decade, a CO2 tax on the production of coal, oil and gas, called a Climate Damages Tax, would yield 900 billion dollars in OECD countries for managing the climate crisis.

The call for international CO2 taxes is almost as old as the Framework Convention on Climate Change itself. As early as 2006, the then Swiss Federal President Moritz Leuenberger used the Climate Conference to call for a global CO2 tax. Concrete agreement at the UN never stood a chance, however. But in view of the UN negotiations on a new climate finance target at the COP29 this coming November in Baku, pressure is growing for the available funding to be increased. This has recently prompted a range of players and countries to call for international CO2 taxes or other methods of financing based on the polluter-pays principle. The approaches vary widely, spanning national tax on profits from oil extraction, voluntary contributions from the extraction industry, and legally requiring enterprises to accept climate accountability. All approaches to international taxes will, however, require political will at the national level. Switzerland, too, should levy "polluter-pays" taxes on enterprises that profit from the fossil fuels business, in that way increasing its contributions to international climate finance.

The "gilets jaunes" – or how not to do things

Additional funds could be raised for ecologically restructuring our societies not only by levying additional taxes on fossil fuel producers, but also if governments asked their consumers to pay more. However, if the restructuring is to be not just ecological but also social, caution is advised when deciding on the right type of CO2 consumer tax. France, for example, has unpleasant memories of the violent street clashes between the "gilets jaunes" (yellow vests) and the police about six years ago in the middle of Paris. Those protests were triggered simultaneously by an increase in the fuel tax (eco-tax) that the French President wanted to levy on every litre of diesel being dispensed by that country's petrol pumps. By his reckoning, it would have garnered an additional 15 billion euros in revenue for the State. But this tax would have affected everyone equally: rich and poor, including people racing their Porsche TDI along empty French country roads, as well as those living in far-flung, non-metropolitan parts of France badly served by public transport and dependent on their rickety diesel vehicles in everyday life. The "gilets jaunes" movement was therefore supported not only by climate deniers and automobile enthusiasts, but also by many people whose already tight monthly budgets would have been busted by this diesel tax. This toxic mix constituted political dynamite. The liberal French government backed down and also slowed the pace of its climate policy agenda. At the same time, President Macron further renounced the reintroduction of a "solidarity tax" on high net-worth individuals, which had been introduced in the 1980s by the long-standing socialist President François Mitterrand, and which Macron had abolished as one of his first official acts in power. That would possibly have taken the social policy wind out of the sails of the "gilets jaunes".

No climate justice without tax justice

Today there is a highly progressive wealth tax with a social and environmental dimension, among other places, on the agenda of the G20 countries. In a report published in November 2023, the NGO Oxfam International concludes that a global wealth tax on all millionaires and billionaires would raise 1700 billion dollars annually worldwide. An additional penalty tax on investments in climate-damaging activities could bring in a further 100 billion dollars. Combining these measures with a 60-per cent income tax on the 1 per cent with the highest incomes would generate an additional 6400 billion. Depending on business cycle and price trends, an excess profits tax can also generate massive amounts of additional revenue. According to Oxfam, such a tax would have raised another 941 billion dollars in each of the years 2022 and 2023 when inflation was high. These measures therefore have the potential to garner an additional tax take of at least 9,000 billion in a single year.

The premise of the 2024 report on the funding of sustainable development published by the United Nations Department for Economic and Social Affairs (DESA) is that the funding and investment shortfalls in connection with the UN Sustainable Development Goals of the 2030 Agenda amount to 2500 to 4000 billion US dollars. Using just the tools mentioned above, the 2030 Agenda could therefore be easily funded up to 2030 – to say nothing of reforms in other areas of development finance. Unlike Macron's diesel tax, a global wealth tax would certainly be in line with the polluter-pays principle within the meaning of international climate policy. According to Oxfam, in 2019, the world's richest 1 per cent accounted for 16 per cent of all global CO2 emissions. This meant that they produced as much CO2 as the poorer 66 per cent of the world's population, that is to say 5 billion people.

Climate and tax justice on a world tour: an overview of some global approaches and initiatives

- Washington D.C. – Climate Damages Tax: Current study by the Heinrich Böll Foundation on a CO2 tax on coal, oil and gas production. While some of the proceeds would be earmarked for the UN fund to cover climate-related loss and damage, another portion would go towards managing the climate crisis domestically. Producing countries in the Global South could also introduce the tax and use the proceeds in their own countries. Increasing the tax annually would also create an incentive to phase out fossil fuels. Civil society endorses this concept.

- Nairobi – Africa Climate Summit: Already a year ago, African countries called for global CO2 taxes on the trade in fossil fuels, on marine and air traffic, and also for a global financial transaction tax, in order to boost investment in climate protection.

- Baku – Climate Finance Action Fund: As President of COP29, Azerbaijan is keen to build up a climate fund that is fed by voluntary contributions from coal, oil and gas producers. The fund's Board of Directors would decide on the distribution of the monies raised from the participating production industry. The previous COP host, the United Arab Emirates, proved that this is not a good idea. Climate Home News recently uncovered the fact that resources from their newly founded climate fund were being invested in natural gas projects and airports.

- Paris – Task Force for Global Solidarity Taxes: Last year, France, Barbados and Kenya formed a task force to work together with other interested countries on ideas for global solidarity taxes applicable to the fossil fuels industry, financial transactions, as well as marine and air traffic. Civil society observers in France, however, view this as both international image cultivation by President Macron and a diversion from international negotiations on climate finance or the UN Tax Convention.

- London – Excess profits tax on oil and gas production: Following the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, the United Kingdom introduced an excess profits tax on companies producing oil and gas in the UK, and raised 2.6 billion pounds in the first year. The new Labour Government is planning to further increase the tax rate. The proceeds go into government coffers.

- Pari Island (Indonesia) – Lawsuit against Holcim: Pari Island is being flooded with growing frequency and is being swallowed up by the sea, metre by metre. Four residents have initiated litigation in the Zug Cantonal Court against the Holcim cement company over its climate responsibility, and are demanding that the company reduces its emissions, pay compensation for the climate damage they have suffered, and contribute financially towards adaptation to global warming.

- Rio de Janeiro – Global wealth tax: In late June, G20 finance ministers discussed a model for the global wealth tax devised by the French economist Gabriel Zucman. In principle, it reflects what Oxfam proposes in its report (see text). As President of the G20 this year, Brazil raised the idea in the club of the world's 20 leading economies. After much fanfare in the early stages, the summit's final declaration could only produce fine-sounding rhetoric. The project had reportedly been hampered, among other things, by disagreement among participants over the question of whether the UN or the OECD should be tasked with working out such a tax.

- New York – UN Tax Convention: Negotiations between the 197 UN member governments on the Terms of Reference (ToRs) of a Framework Tax Convention concluded successfully in mid-August. From the very beginning, many countries – especially those in the Global South – had come out in favour of including in the ToRs the creation of more effective climate and environmental taxes as an aim of the Convention in its own right. Despite having been highly controversial, this point is now embodied in the text and promises long-term global progress on climate-related taxes with redistributive effects. Elaborating a global wealth tax with a climate-related dimension would be best placed in the hands of the UN, where the prevailing majority dynamics will ensure that such a taxation model would also reflect the specific interests of the countries in the Global South.

- Berne – Initiative for a Future: The Young Socialists wish to impose a 50-per cent tax on inheritances of more than 50 million francs. The Confederation and cantons would then use the proceeds of the tax to "combat the climate crisis in a socially equitable manner and to fund the complete overhaul of the economy that this would require." This is stated in the text of the initiative. As it is well known that the climate crisis cannot be tackled strictly within the borders of Switzerland, the initiative also provides for additional contributions by Switzerland towards the funding of the UN Sustainable Development Goals worldwide.

COP29 – Climate Conference

In November, UN Member States will negotiate a new collective funding target for supporting the countries in the Global South in dealing with the climate crisis. Funding in accordance with the polluter-pays principle is also a part of this discussion. The funding gap is growing dramatically and financial support is simply a necessity if the countries in the Global South are to continue their development using climate-friendly technologies, and avoid more loss and damage thanks to adaptation measures. The pressure for an ambitious funding target is accordingly great, and rich countries are challenged to increase their contributions significantly in the years ahead.

Share post now

global

The Alliance Sud magazine analyses and comments on Switzerland's foreign and development policies. "global" is published four times a year (in german and french) and can be subscribed to free of charge.

Climate justice

No fossil fuel phase-out without climate finance

21.03.2024, Climate justice

Switzerland is not prepared for the burgeoning expectations regarding its future contribution to international climate finance. New funding sources must be found if additional funds are to be allocated for climate protection and adaptation in the Global South.

Extraction of fossil fuels in Bakersfield, USA. © Simon Townsley / Panos Pictures

Last December at the climate conference in Dubai, puzzled media representatives asked Swiss Environment Minister Albert Rösti whether he was comfortable with promoting the phase-out of fossil fuels by 2050. He reassured them that he was. The world will have phased out coal by 2040, he added, in line with Switzerland's position in the plenary. What he did not say was that phasing out coal, oil and gas will require several hundred billion dollars in climate funding for the Global South – per year. And another comparable amount will be needed to fund adaptation in least developed countries – which, despite having produced almost no greenhouse gases, are being ever more greatly impacted by the consequences of the climate crisis – and for compensating those affected. That will be several times the current financing target of $100 billion per year. The financing shortfall for climate protection measures in the poorest countries is growing constantly. Despite this, the funds being provided by those – like Switzerland – who caused the climate crisis, still fall short of the 100 billion promised. Besides, the debt crisis and other factors are hampering the self-funding capacity of least developed countries. Many countries in the Global South feel left in the lurch by the North.

Against this complex backdrop, this year's climate conference will be working out a new funding target. The yardstick will be the extent to which it enables the countries in the Global South to implement ambitious climate protection plans and adapt to global warming as best they can. An ambitious and credible new climate funding target is a must if, in the course of 2025, all countries are to submit new five-year climate plans that are in line with the aims of the Paris Agreement. The stakes will therefore be high when delegates gather in Azerbaijan in November for the negotiations, and expectations placed on the rich countries will rise substantially. Switzerland, too, should therefore be encouraging polluter countries to provide much more public funding for climate finance. In a guest article in Climate Home News, the chief negotiator for the Least Developed Countries (LDCs), Malawi's Evans Njewa, called on negotiating delegations from the Global North to cease hiding behind their parliaments: "They stress that they have no mandate, or possibility to scale up funds, as parliaments will not approve. So, as parliamentarian debates about budgets and allocations begin early in the year, they need to act now", he said.

Swiss Government resisting the need for action

This pattern can also be seen here at home. Despite speaking up, during climate negotiations, for the worldwide phase-out of fossil fuels by 2050 in keeping with the aims of the Paris Agreement, Switzerland is dragging its feet when it comes to funding, as it cannot point to any domestic policy decisions to increase funding contributions. In reality, the Federal Council is not even attempting to obtain additional funding from the parliament. Why is this so?

So far, Switzerland's climate finance contributions have come mainly from the International Cooperation (IC) budget, which itself is already receiving insufficient funds for worldwide poverty alleviation, and is now facing the prospect of yet another massive reallocation of funds towards reconstruction in Ukraine. This means that current climate financing is already being double-counted along with poverty alleviation projects. But new, additional money is needed if Swiss climate funding is to effectively help support climate plans in the Global South. The Federal Council should be working at the legislative level to devise alternative funding options so that IC funds can continue to go towards global poverty alleviation, the strengthening of basic education and health services, and towards other key tasks. A year ago, it entrusted the Administration with working out ways in which Switzerland could provide more climate funding in future. At the end of last year, an externally commissioned study was published without comment on the website of the Federal Office for the Environment. In it, experts recommend that Switzerland should tap into new funding sources, for example, proceeds from the carbon emissions trading scheme. Yet the Federal Council has done nothing so far. The new legislature plan indicates that, for the next three years, the Government has no intention of submitting an item of business on climate funding to the parliament. It will be relying exclusively on the new four-year credit line for international cooperation for the 2025–2028 period, which offers no scope for additional climate funding.

If the Federal Council fails to act – which would be irresponsible in this case, as the climate negotiations are within its remit – the parliament can also take the initiative. During the past winter session, National Councillor Marc Jost brought forward a motion to enable the parliament to draft new legislation on international climate and biodiversity funding.

Without finance, there is no action

The Baku climate conference is fast approaching – so what remains to be done? Switzerland must rethink its previous negotiating position on funding and strive for an ambitious goal that aligns with the needs of the people in the Global South and distributes the financial responsibility fairly among rich countries, as the ones accountable for the climate crisis. Only in this way can coal be phased out by 2040 and all fossil fuels by 2050. The international pressure to agree on an ambitious target will therefore be intense.

This will also inevitably mean greater pressure on Switzerland to scale up its contribution many times over. If funds are to be increased quickly enough, Switzerland must begin the legislative work now and find new sources of climate funding.

Evans Njewa puts it as follows: "We must all remember that without finance, there is no action, and without action we will never be able to manage the climate crisis."

Share post now

global

The Alliance Sud magazine analyses and comments on Switzerland's foreign and development policies. "global" is published four times a year (in german and french) and can be subscribed to free of charge.

Article

Carbon offsetting abroad: the illusion of voluntary action

07.12.2023, Climate justice

Pressure from civil society and the media has rightly discredited the carbon markets. The current system is not delivering on its promises and is harming the Global South.

Edited by Maxime Zufferey

Excessive recourse to offsetting instead of a substantial reduction in emissions is in no way sustainable.

© Ishan Tankha / Climate Visuals Countdown

The voluntary carbon market facilitates the trading of carbon credits. It allows a company to continue emitting CO2 while offsetting its own emissions by funding projects that reduce emissions elsewhere. On paper, carbon offsetting is seen as the most effective market-based approach for achieving results in terms of reducing global emissions. The idea is to maximise the efficiency of available resources in reducing emissions by using them where they are most beneficial. For example, once a company has reduced its own emissions as cost-effectively as possible, it could then allocate resources to low-carbon technology projects or reforestation projects to arithmetically offset the emissions it has not yet reduced. In practice, however, the assumption that cheap carbon credits are the answer is much criticised. They are seen as undermining the goal of reducing emissions and helping, counterproductively, to maintain the status quo. More recently, increased scrutiny by civil society has raised doubts about the often-misleading promises of 'carbon neutrality' made by some companies under the guise of offsetting, while their emissions continue to rise.

Carbon markets: taking stock

The carbon market has been controversial since its inception in the late 1980s and especially since the signing of the Kyoto Protocol in 1997. Its development has given rise to parallel markets, namely the 'compliance' market and the 'voluntary' carbon market, which are sometimes difficult to distinguish due to the potential overlap between them. The compliance market involves mandatory emission reductions and is regulated at the national or regional level. The best known of these markets is the European Union Emissions Trading Scheme (EU ETS), which Switzerland joined in 2020. Under this mechanism, certain large emitters – power plants and large industrial companies – are subject to an emissions cap, which they can offset by buying allowances from other members who have reduced their emissions beyond the target. This cap is reduced each year. A laborious implementation process, the system has led to a certain reduction in emissions in the sectors concerned. However, there has been criticism that it has been too generous in allocating free allowances to large emitters, that it has allowed an influx of international credits and that it has not set sufficiently ambitious reduction targets. Furthermore, the price of carbon is still too low; it should reflect the social cost of a tonne of emissions and be gradually increased to USD 200. The voluntary market, on the other hand, currently has no minimum reduction targets and remains largely unregulated. Outdated carbon credits are also frequently used, as are credits whose quality and price vary widely, sometimes even below USD 1.

The limits of the voluntary market

The crisis of confidence that has hit the voluntary carbon market is not only due to its unregulated nature and inadequate framework, but also to the technical limitations of the mechanism. Carbon credits rarely correspond to the exact unit of 'compensation' claimed, and their impact is systematically overestimated. This is due to the use of an unreliable quantification method and the lack of a comprehensive monitoring system that is genuinely free of conflicts of interest. Moreover, it is often unclear whether offset projects meet the additionality criterion, i.e. whether they would not have been implemented anyway, without the financial contribution of carbon credits. This is particularly true for renewable energy projects, which have become the most cost-effective source of energy in most countries. Another major challenge is double counting, i.e. the crediting of carbon credits by both the host country and the foreign company. This practice violates the principle that a credit can only be claimed by one and the same entity. The Paris Agreement has increased the risk of double counting because, unlike the Kyoto Protocol, it also requires developing countries to reduce their emissions.

There are also many doubts about the permanence of registered offsets. The extraction and burning of fossil fuels is part of the long-term carbon cycle, while photosynthesis, and hence the sequestration of carbon by trees or the absorption by the oceans, is part of the short-term biogenic carbon cycle. Trying to offset the long-term accumulation of CO2 in the atmosphere with offset projects limited to a few decades therefore seems illusory. In addition, anthropogenic climate change itself, with the increasing frequency of fires and droughts and the spread of pests and diseases, threatens the storage of carbon in temporary sinks such as soils and forests. There is also the risk of leakage, where a project to protect forests in one region leads to deforestation elsewhere. As for the prospects for technological solutions using carbon capture and sequestration devices, these should not be overestimated. They are currently neither competitive nor available on the scale required in the short term. Even in the future, they are likely to play only a limited albeit necessary role.

Carbon colonialism perpetuates injustice

More fundamentally, over-reliance on offsets rather than substantial emission reductions is unsustainable. As Carbon Market Watch points out in its report (Corporate Climate Responsibility Monitor) on the integrity of the climate change targets of companies claiming to be pioneers, the implementation of these companies' current 'net-zero roadmaps' is highly dependent on offsets. At the current rate, demand for land to generate carbon credits will far outstrip availability, directly threatening the survival of local communities, biodiversity and food security. At the same time, emission reduction projects popular in the voluntary market, such as reforestation and other 'nature-based solutions', are often based on 'fortress models' of conservation, in which protected areas are fenced off and militarily protected – at the expense of the original inhabitants. Far from being "empty spaces" to be planted with trees by polluters, these projects often take place on land inhabited by indigenous communities. The new gold rush for nature-based solutions through the privatisation of natural carbon sinks is exacerbating historic and complex land conflicts and confronting forest dwellers with the real threat of dispossession. This rings even truer when such projects deprive indigenous communities of their right to self-determination and to give their free, prior and informed consent to all projects affecting their territories.

Overall, the current system is woefully inadequate to the urgency of the climate crisis, and is also deeply unjust. It grants pollution rights to the biggest greenhouse gas emitters – mainly large corporations and economies in the Global North. They are allowed to continue with business as usual, while economic systems and lifestyles, mainly in the Global South, are restricted. This carbon colonialism thus shifts the responsibility for combating climate change and corporate deforestation onto local communities that have contributed the least to climate change.

Share post now

global

The Alliance Sud magazine analyses and comments on Switzerland's foreign and development policies. "global" is published four times a year (in german and french) and can be subscribed to free of charge.

Article

A new El Dorado for commodity traders

07.12.2023, Climate justice

In a carbon market that has demonstrated its limitations, an unexpected player has invited itself to the negotiations. Commodity traders have recently stepped up their CO2 trading, without scaling back their fossil fuel business operations.

Emissions trading has also attracted strong interest of the largest emitters, above all commodity traders.

© Nana Kofi Acquah / Ashden

Natural gas labelled "CO2-neutral" or concrete with "net zero" certification: the list of seemingly climate-neutral consumer goods has grown steadily over recent years. The accounting trick behind carbon offsetting is that a greenhouse gas emitter – whether a company, an individual or a country – pays for another player to avoid, reduce or cease their emissions. This enables companies to market themselves as they see fit by presenting themselves to their customers as committed climate protectors, even though they are not reducing their own emissions. The voluntary carbon market has reached a crossroads, oscillating between an outright boom and the crisis of confidence recently triggered by greenwashing allegations.

On the one hand, there is the economic reality of a voluntary carbon market, which quadrupled to USD 2 billion in 2021 alone – and could well reach USD 50 million by 2030 – and which is attracting strong interest from the biggest emitters, foremost among them commodity traders. This exponential market growth is attributable, in part, to the growing number of "net-zero" commitments by the private sector in the face of popular pressure and, in part, to the economic and logistical alternative that offsetting represents compared with reducing carbon footprints. On the other hand, damning reports about the poor quality of voluntary carbon market projects are coming thick and fast. They caution against the unbridled development of a market whose real impacts on climate protection is depicted as ranging from negligible to downright counterproductive. The ETH Zurich and the University of Cambridge have shown, for example, that a mere 12 per cent of all existing credits in fields where most offsetting occurs – renewable energies, cooking stoves, forestry and chemical processes – actually reduce emissions. Reports on the flagship South Pole project Kariba by the investigative journalism platform Follow the Money have told of vastly overestimated figures. The Zürich-based company then cancelled its contract as Carbon Asset Developer for the project in Zimbabwe. As for the NGO Survival International, it denounces a voluntary carbon offset project in northern Kenya, which is taking place on land belonging to indigenous communities. Their investigation uncovered potentially serious human rights violations that are jeopardising the living conditions of local livestock farmers.

What then is the voluntary carbon market? An ill-conceived marketing solution and dangerous distraction from the urgent need for transformative climate protection measures by the private sector? Or a genuine business opportunity to support corporate efforts to tackle climate change and a much-needed multi-billion-dollar cash injection for projects to cut emissions and protect the biodiversity in developing countries?

CO2 certificates – the commodity of the future

As a pioneer in the bilateral trade of CO2 certificates under the Paris Agreement, Switzerland is a key player in the carbon market, including in its voluntary segment. It is home to South Pole, the leading provider of voluntary CO2 certificates, and to Gold Standard, the second largest certifier. Perhaps more surprising is the market positioning of the Swiss and Geneva-based commodity trading giants, admiralships of a commodities sector that is posting one record a year after another. These new investments are explained by the potential of this opaque market to generate substantial margins and prolong business as usual. It is worth noting that this market is unregulated when it comes to prices or the distribution of revenue from CO2 credits. According to Hannah Hauman, Trafigura's Head of Carbon Trading, the carbon segment is now the world's biggest commodity market, having already overtaken the crude oil market.

In 2021, Trafigura – one of the world's largest independent oil and metal traders – decided to open its own carbon trading office in Geneva and to launch the largest mangrove reforestation project on the Pakistani coast. A year later, however, its coal trading volume increased to 60.3 million tonnes. In its 2022 annual report, not only did Geneva-based energy trader Mercuria declare its carbon neutrality, it also disclosed that 14.9 per cent of its trading volume comprised carbon markets, versus 2 per cent in 2021. In early 2023, Mercuria co-founder Marco Dunand announced the creation of Sylvania, a USD 500-million investment vehicle specialising in nature-based solutions (NbS). Shortly thereafter, he launched the first jurisdictional programme with Brazil's Tocantins State to cut emissions from deforestation and forest degradation, with a volume of up to 200 million in voluntary carbon credits. Even so, at almost 70 per cent, oil and gas still make up the company's main business. Vitol, Mercuria's neighbour on the shores of Lake Geneva and the world's largest private oil trader, can look back on over 10 years of experience in carbon markets and is considering expanding its activities in that field. In carbon trading, the company is aiming for a market volume comparable to its share of the oil market. For 2022, that share was 7.4 million barrels of crude oil and oil products per day, which corresponds to more than 7 per cent of global oil consumption. Communication is less transparent from crude oil trader Gunvor, which is also planning to ramp up its CO2 trading volume in the years ahead; the same goes for Glencore, which has a years-long track record in the area of biodiversity-related offset payments, central to its sustainability strategy. For 2022, Glencore estimated its emissions throughout the value chain to be 370 million tonnes of CO2 equivalent, or more than three times Switzerland's total CO2 emissions.

These companies describe themselves as drivers of the transition, and take credit for having accelerated that process by incorporating carbon trading into their portfolios. The fact remains that they are pursuing a two-pronged strategy by investing in both low-carbon and fossil fuels, with the latter still clearly dominating. Besides, none of these commodity traders has yet announced their intention to phase out fossil fuels, which is indispensable if we are to remain below the 1.5°C temperature increase stipulated in the Paris Agreement. The opposite is the case: companies are relying heavily on carbon offsetting to fulfil their climate undertakings, and this allows them to continue pursuing their short-term profit targets while delaying the worldwide phase-out of fossil fuels. Given the absence of regulations to limit fossil fuel investments and climate-degrading activities, it is illusory to think that the commodity trading industry can bring about the transition and that the goals can be attained through the voluntary carbon market. So long as companies fail to do the utmost to lower their own emissions, nature-based solutions will remain greenwashing, and declarations of intent in favour of the transition will be no more than a sham. These companies are pretending to put out a massive fire that they themselves keep feeding.

Dubai as referee

The UN Climate Change Conference (COP28), taking place in Dubai in December 2023, is expected to set the course for the future and the credibility of the voluntary carbon market. Among other things, the negotiations will cover the implementation of Article 6.4 of the Paris Agreement, which could serve as a harmonised framework for a genuine worldwide carbon market. And to this end, the prominent role of COP President Sultan Al Jaber, CEO of the world's 11th largest oil and gas producer, the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (ADNOC) – which has just opened a carbon trading office – and the massive presence of fossil fuel and commodity multinationals at the negotiating table could well tip the balance. The requirements in respect of transparency, generally applicable rules and effective controls in the voluntary carbon market are therefore likely to be watered down.

While advocates of the voluntary carbon market acknowledge some of the sector's current shortcomings, they remain convinced that the various self-regulation initiatives, such as the Voluntary Carbon Markets Integrity Initiative (VCMI), and the formulation of standards will lead to a clear demarcation of credible carbon credits. Opponents, for their part, do not believe in the transformative power of a voluntary, self-regulating market. They see the discussion around carbon offsetting as a possible diversionary tactic that reinforces the status quo. They argue for a complete paradigm shift. The current carbon offset market based on the "tonne for tonne" principle – i.e., a tonne of CO2 emitted somewhere is mathematically offset by a tonne of CO2 saved elsewhere – should be transformed into a separate market for climate contributions based on the "tonne for money" principle, i.e., a tonne of CO2 emitted somewhere is financially internalised at the true social cost of a tonne of emissions. Thus, by setting a sufficiently high internal price for their residual emissions, carbon credits would become the expression of the environmental and historical responsibility of the private sector, without the latter being able to claim paper carbon neutrality. Only then would this instrument be a useful complement to quantifiable reduction commitments – and never a substitute for them! There is also an urgent need for rigorous due diligence for all carbon projects, including mechanisms to safeguard human rights and the biodiversity, as well as an effective complaints mechanism.

Share post now

Article

Sustainable Finance: a generational project

06.12.2023, Climate justice, Finance and tax policy

In 2015, governments committed to aligning financial flows with the climate objectives of the Paris Agreement. Where do things stand with implementation? What is Switzerland doing? A stocktake.

The financial sector's commitment to climate protection is very contradictory.

© Adeel Halim / Land Rover Our Panet

Signing the Paris Agreement in 2015 the international community committed to significantly reducing greenhouse gas emissions, aiding developing countries in climate change mitigation and adaptation, and directing both public and private finances into a low-carbon economy and climate-resilient development. Article 2.1(c) of the Paris Agreement embodies this goal. The jargon therefore speaks of "Paris alignment".

On 3 and 4 October, government officials, business leaders and representatives from NGOs came together at the 3rd Building Bridges Summit for a two-day workshop in Geneva to explore this orientation and its alignment with Article 9 of the Paris Agreement. This was done with a view to the first "global stocktake" to be conducted at COP28. Under Article 9, developed countries pledged to extend financial support to developing nations for climate change mitigation and adaptation measures. Numerous delegates and NGOs in Geneva have raised concerns that industrialised countries are emphasising private finance alignment while disregarding their commitment to assisting developing countries.

Financial flows for economic activities based on fossil fuels continue to far surpass those meant for mitigation and adaptation measures. The most recent IPCC synthesis report affirms that sufficient capital exists globally to close the worldwide climate investment gaps. The predicament is therefore not a shortage of capital, but rather the ongoing mismanagement and misallocation of funds that is impacting both public and private capital flows. Nevertheless, redirecting financing and investment towards climate action, primarily in the neediest and most vulnerable nations, is no silver bullet. The challenges of a "just transition" go much further, and developing countries also expect financial support from the North.

Responsibility of governments

Businesses, including those in the financial sector, are not bound by the Paris Agreement. Governments therefore have a responsibility to translate climate change commitments into national legislation. Put simply, "Paris alignment" requires governments to ensure that all financial flows contribute to achieving the climate goals of the Paris Agreement. Implementing Article 2.1(c) will require a variety of instruments, and it is primarily up to individual governments to identify the regulatory frameworks, measures, levers and incentives needed to achieve alignment. This will require concrete steps leading to tangible and measurable results for individual companies and financial institutions.

What is Switzerland doing?

By ratifying the Paris Agreement, Switzerland has also committed to making its financial flows compatible with climate goals. The Federal Council is also working with the industry to ensure that the financial centre plays a leading role with regard to sustainable finance. However, it is still relying primarily on voluntary measures and self-regulation.

With the Climate and Innovation Act, the Swiss electorate decided, in June 2023, that Switzerland should achieve climate neutrality by 2050. Interim greenhouse gas reduction targets have been set, along with precise benchmarks for certain sectors (construction, transport and industry). Broadly speaking, all companies must have reduced their emissions to net zero by 2050 at the latest. With specific reference to the goal of aligning financial flows with climate goals, Article 9 of the Climate Act stipulates that: "The Confederation shall ensure that the Swiss financial centre contributes effectively to low-carbon, climate-resilient development. This includes measures to reduce the climate impact of national and international financial flows. To this end, the Federal Council may conclude agreements with the financial sector aimed at aligning financial flows with climate objectives".

The role and responsibility of Switzerland as a financial centre

The facts are clear: the Swiss financial centre is the country's most important "climate lever". The CO2 emissions associated with Switzerland's financial flows (investments in the form of shares, bonds and loans) are 14 to 18 times greater than the emissions produced in Switzerland! It would therefore be logical for the Federal Council to give priority to these financial flows. Given its size – around CHF 7800 billion in assets under management – the Swiss financial centre could make a significant contribution to achieving the climate goals. However, this would require effective measures here at home to help redirect financial flows. This would include credible CO2 pricing, both domestically and – as yet unimplemented – internationally.

Range of measures for Swiss companies and financial market players

From January 2024, large companies – including banks and insurers – will be required to publish a report on climate matters covering not only the financial risks a company faces from its climate-related activities, but also the impact of its business activities on the climate ("double materiality"). The report must also include companies’ transition plans and, "where possible and appropriate", CO2 emission reduction targets that are comparable to Switzerland's climate targets. Like the UK and a number of other countries, the European Union has introduced similar obligations. Thus, for once, Switzerland is not lagging behind.

PACTA Climate Test

Starting in 2017, the Federal Council has recommended that all financial market players – banks, insurers, pension funds and asset managers – should voluntarily participate in the "PACTA Climate Test" every two years. The aim is to analyse the extent to which their investments are in line with the temperature target set by the Paris Agreement. The test covers the equity and bond portfolios of listed companies and the mortgage portfolios of financial institutions. The PACTA is designed to show the portfolio weight of companies operating in the eight most carbon-intensive industries, which account for more than 75 per cent of global CO2 emissions (oil, gas, electricity, automobiles, cement, aviation and steel).

However, participation in the PACTA test remains voluntary and participants are free to choose the portfolios they wish to submit. Furthermore, the publication of individual test results is not (even) mandatory for financial institutions that have set themselves a net-zero target for 2050. The Federal Council recommends rejecting a motion calling for improvements to these aspects, arguing that existing decisions are already sufficient.

Self-declared net-zero targets

Many Swiss financial institutions have voluntarily set themselves carbon-neutral targets under the auspices of the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ). The Federal Council supports this approach. However, these initiatives raise crucial questions about transparency and credibility. What is the percentage of financial institutions that have set net-zero targets? What is the percentage of assets and business activities that will actually be net zero by 2050? How comparable is the information, i.e., final and interim targets and progress made by financial institutions? To increase the transparency and accountability of financial actors, the Federal Council had originally proposed the conclusion of sectoral agreements with them. This was rejected by the financial lobbies. However, the Climate Act now envisages the conclusion of such agreements, and the Federal Department of Finance is to submit a report on the matter by the end of the year.

Swiss Climate Scores

The Swiss Climate Scores (SCS) were developed by the authorities and industry and introduced by the Federal Council in June 2022 in keeping with GFANZ. The basic idea is to create transparency regarding the Paris alignment of financial flows in order to encourage investment decisions that contribute to achieving the global climate goals. Here too, the approach remains voluntary for financial service providers.

At the Building Bridges Summit, the CEO of the asset management firm BlackRock Switzerland lamented the low uptake of the SCS in her industry. This confirmed the misgivings expressed by Alliance Sud when they were introduced. The daily newspaper NZZ also recently noted the low uptake and inconsistencies in implementation by financial institutions – describing the SCS as a "refrigerator label" for financial products compared to the EU's sophisticated regulatory framework.

Paradigm shift

Implementing Article 2.1(c) of the Paris Agreement will therefore also be a major undertaking for Switzerland. The range of largely voluntary measures adopted so far clearly falls short of the Paris commitments. A paradigm shift is therefore urgently needed.

The Federal Council recently proposed the adoption of a motion calling for the creation of a "co-regulation mechanism" and a commitment that this mechanism would become binding "if, by 2028, less than 80 per cent of the financial flows of Swiss institutions are on track to achieve the greenhouse gas reductions envisaged in the Paris Agreement".

It is now up to the parliament to take the first steps to tackle this generational project.

Share post now

Investigation

New electric buses in Bangkok – no substitute for climate protection in Switzerland

11.12.2023, Climate justice

Switzerland is celebrating the world's first carbon offset programme under the Paris Agreement that will help the country fulfil its own climate goals. Emissions are being reduced in Bangkok through the co-funding of electric buses. A detailed study by Alliance Sud and Fastenaktion reveals that the investment in electric buses in Bangkok would have taken place by 2030 even without an offset programme.

Bangkok, Rachadamri road, 11th October 2022.

© KEYSTONE / Markus A. Jegerlehner

Under the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, industrialised countries were already able to offset greenhouse gas emissions through projects in the Global South. The Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) was developed for that purpose. The voluntary offset market developed in the wake of the CDM, for example, allowing companies to promote "carbon neutral" products without actually reducing their emissions to zero. Both mechanisms, the CDM and the voluntary mechanism, have repeatedly attracted criticism. Studies and research papers show that many of the associated climate projects eventually turn out to be largely useless, and in some cases, harmful to local communities.

The Paris Agreement, which succeeded the Kyoto Protocol, redefined the carbon market and made a distinction between an intergovernmental mechanism (Article 6.2) and a multilateral mechanism (Article 6.4). Under the Agreement, all countries are required to pursue the most ambitious possible climate policy. Article 6 provides that the aim of both mechanisms is to allow for higher ambitions through such cooperation. In other words, carbon emissions trading should enable countries to lower their emissions more quickly. In the negotiations, Switzerland did much to promote this bilateral trade in certificates, and is now leading the way in operationalising it. Switzerland has already signed a bilateral agreement with 11 partner countries, and another three agreements are expected to be concluded at COP28 in Dubai.

Art. 6 of the Paris Agreement

1. Parties recognize that some Parties choose to pursue voluntary cooperation in the implementation of the nationally determined contributions to allow for higher ambition in their mitigation and adaptation actions and to promote sustainable development and environmental integrity.

[...]

Domestically, the Swiss government and the centre-right parliamentary majority interpret this possibility as carte blanche not to pursue the country's stated goal of a 50 per cent reduction in emissions by 2030, within Switzerland. In other words, the possibility to buy certificates is not being used to reach higher goals. This is eminently clear from the current review of the CO2 Act, as it provides for remarkably limited emission reductions in Switzerland for the 2025–2030 period. Compared to 1990, the rollover of the measures currently in place is expected to yield a 29 per cent reduction by 2030. Under the government's proposal, the new CO2 Act is expected to produce a mere five percentage point reduction, i.e., -34% vis-à-vis 1990. However, if Switzerland is still to achieve its 50 per cent reduction target on paper, it will have to purchase more than two-thirds of the additional reduction needed (15 per cent of 1990 emissions) in the form of certificates from partner countries. The partner countries must forego including those emission reductions in their greenhouse gas balance. As the first chamber, the Council of States proceeded to further water down the government's already weak domestic ambitions in the CO2 Act, i.e., to a less than four percentage point reduction in five years. In so doing it has intensified the pressure, in the short time remaining until 2030, to produce sufficient certificates in partner countries, and this to very exacting qualitative requirements. That this is no simple matter is borne out, not least of all, by the problems mentioned initially, which have already come to light in the CDM and the voluntary carbon market.

Switzerland has approved three offset programmes since November 2022. Two were developed by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). The first is intended to reduce the output of methane from rice farming in Ghana, and the second, to promote the use of decentralised mini-solar panels on outlying islands in Vanuatu. Both programmes are intended to serve the federal administration's voluntary carbon offsetting endeavours.

The third programme approved – the Bangkok E-Bus Programme – is the world's first, under the Paris Agreement, in which emission reductions are to count towards the reduction goals of another country, namely Switzerland. The programme was commissioned by the KliK Foundation and is being implemented by South Pole, in partnership with the Thai company Energy Absolute – which is 25 per cent owned by UBS Singapore. Its purpose is the electrification of publicly licensed buses in Bangkok, which are operated by the private company Thai Smile Bus. The additional funding derived from the sale of certificates to the KliK Foundation in Switzerland is intended to cover the price difference between traditional and electric buses, as investing in new electric buses is not financially viable for private investors and would therefore not happen. Replacing old buses and operating some new bus lines is expected to save a total of 500,000 tonnes of CO2 between 2022 and 2030. The new buses began operating in autumn 2022.

Alliance Sud and Fastenaktion have studied the publicly available documents on the Bangkok E-Bus Programme and identified shortcomings in the additionality aspect, and in the quality of the information provided. They heighten concerns that the purchase of offset certificates is no equivalent substitute for domestic emission reductions. The certificate trading approach is fundamentally at odds with the principle of climate justice, whereby the countries mainly responsible must cut their emissions as quickly as possible.

KliK

The Foundation for Climate Protection and Carbon Offset KliK is owned by Switzerland’s fuel importers. The CO2 Act requires these companies, at the end of each year, to surrender offset certificates to the federal government, whether from Switzerland or abroad, covering some part of their fuel emissions. To that end, KliK develops programmes with partners through which it can purchase certificates

Shortcomings regarding additionality

One key condition for a one-tonne CO2 reduction elsewhere to become an equivalent substitute for one's own reduction is that of additionality. This means that without the additional funding from emission certificates, the emission-reducing activity such as replacing diesel-driven buses with electric ones, would not have taken place. This condition is crucial if a climate benefit is to exist. It is also enshrined in the CO2 Act. This is because a traded tonne of CO2 legitimises a further tonne of CO2 emissions by the purchaser, which is then shown on paper as a reduction.

Those in charge of the Bangkok E-Bus Programme must therefore prove that without the programme, the public bus lines run by private operators like Thai Smile Bus would not be using electric buses before 2030. Various factors must be considered in the process: For one thing, this electrification must not have been part of an already planned government subsidy programme, and for another, this investment may not be undertaken by private parties anyway.

Subsidy programme: The official programme documentation barely explains the government's failure to subsidise the introduction of e-buses to replace the old buses, which also contribute substantially to local air pollution. According to the programme documentation, promoting electromobility and energy efficiency in the transport industry in general is part and parcel of government plans. But subsidies were granted only to public bus operators, not to private ones, in other words, not to the programme's target group. The document does not explain why government subsidies are available only for public operators. Besides, no mention is made of Thai subsidies (mainly tax advantages) for private investors engaged in the manufacture of batteries and E-buses, for instance, and of which Energy Absolute is also a beneficiary.

Investment decision: For additionality to exist, the project owner must demonstrate that no positive investment decision could have been possible without the emissions-related funding. To that end, the programme documentation contains a calculation which is meant to prove that without the additional funding from the sale of certificates, the private investment would not have been profitable and hence would not have taken place. The sales proceeds are expected to cover the cost difference between the new purchase of traditional buses and the new purchase of e-buses, calculated for their entire service life. However, neither the price difference nor the way it was calculated is mentioned in the official documents. When contacted, KliK furnished no detailed information, stating that this was "part of the contract negotiated for financial support of the E-Bus Programme", in other words, a private matter between KliK and Energy Absolute. It is therefore not possible to examine the key argument as to why the funding programme is needed for the e-buses. Consequently, additionality is at best non-transparent, and at worst, non-existent. But the price difference argument is also remarkable, in that as an investment firm, Energy Absolute specialises in green technologies. As such, the firm would hardly have decided to invest in the purchase of buses with combustion engines. On the other hand, it is plausible that a major investment in e-buses would have taken place in the next few years anyway, because, even before the 2022 launch start of the programme, Thai Smile Bus had been operating e-buses on the streets of Bangkok, a fact borne out by several media and a Twitter post with pictures (see Figure below). Hence, there must have been funding pathways for e-buses prior to the Bangkok E-Bus Programme. This clearly contradicts the assertion that e-buses would not have been introduced in Bangkok without the offset programme. At a minimum, the programme documentation should have laid out this problem in detail and explained why, despite this, the programme is deemed to entail additionality.

Lack of transparency and poor quality of the publicly available information