Share post now

Opinion

In the shadow of the volcano

23.03.2023, Climate justice

Sandy beaches, rum and colourful fish. That is the Caribbean from the travel catalogue. What is not mentioned is that the Caribbean islands are especially vulnerable to natural phenomena.

© Karin Wenger

As we sail along Montserrat's west coast, it suddenly hits me – an awful stench. Perhaps a flying fish that jumped on deck without being noticed? No. It stinks of rotten eggs. And then we see them – little clouds of sulphur billowing from the mouth of the volcano and wafting on the wind to us out at sea. The Soufrière Hills volcano is in eruption, and has been for almost thirty years now.

Its 1995 eruption took the islanders by surprise. Having shown no sign of life since the 16th century, the Soufrière Hills volcano suddenly awoke from a deep sleep after 270 years. The volcano began spewing ash and lava, and the capital Plymouth, which lies on the western side of the volcano, had to be evacuated. Most of the 11,000-plus islanders moved away. As Montserrat is still a British Overseas Territory, many went to England, where they got help.

Herself a teenager at the time of the eruption, Vernaire Bass, too, left her homeland back then. "Not only was the infrastructure destroyed, but there was no longer any work or a future for us," recalls Bass, who now heads the island's National Museum, amongst other things. Besides, she says, the volcano was not the only danger. "Starting in June every year, we have to countenance the possibility that a hurricane could destroy all that we have built up. That means living in constant uncertainty. The upshot is that many islanders – not just here, but all around the Caribbean – suffer from PTSD, Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, because of this." In 1989, for example, Hurricane Hugo tore across the Caribbean and caused extensive devastation, including in Montserrat. The capital Plymouth and the island's infrastructure were rebuilt over six years, there were new schools and a new hospital; and when everything was restored, the volcano erupted. "Without the help from England,” Vernaire recounts, “the island might well be deserted today. We simply wouldn't have had the money to rebuild everything."

Montserrat is not the only volcanic island in the region. Here, the Caribbean plate collides with other plates, creating friction and causing repeated earthquakes and volcanic activity. In the region of the Antilles in particular, which includes Montserrat, the interaction between the North and South American and Caribbean plates is such that extreme tensions can build up here. The hurricane season runs from June to November every year. In 2022, 14 major storms and eight hurricanes swept across the Caribbean. They caused major damage to some islands. Cuba, for instance, was hit by Hurricane Ian last September. More than three million Cubans were directly affected and tens of thousands lost their homes. Climate researchers tell us that if the temperature rises by two degrees compared to the pre-industrial era, the probability of hurricanes, storms and severe flooding in the Caribbean would increase fivefold. As a future scenario, that would mean the destruction of habitat and the displacement of millions of people.

Montserrat, too, was hit by a massive hurricane last year. Hurricane Fiona swept across the island on 16 September 2022. The worst affected was Plymouth, the former capital, which the volcano had already destroyed. The volcano has been in constant eruption since 1995. Over recent years, its dome has repeatedly grown by hundreds of metres, only to collapse again. The last dome collapse occurred in 2010. Two thirds of the island, including Plymouth, and a radius of ten nautical miles around the southern part of the island still constitute a restricted zone. It is thanks to special authorisation that we are able to visit what remains of Plymouth. Here, where there was once bustling activity, now lie just ruins, enveloped in an eerie silence. The volcano has literally incinerated and swallowed up the city. Only the top floors of some three-storey buildings are still visible; where a long cruise ship pier once stood, only the tiny rump of a pier can be seen – the volcano has ejected so much material that the coastline has moved a hundred metres into the sea. Where there was once water, there is now new land.

The volcano is currently being monitored around the clock by a group of international scientists from the Montserrat Volcano Observatory. One of them is José Manuel Marrero, a Spanish volcanologist. He says: "The danger of a new and massive eruption is real. We just don't know when it will take place."

Despite this, Vernaire Bass returned to the tiny Caribbean island three years ago, after more than two decades in the UK. "I was longing for my homeland and wanted to play a part in the island's development," she says. But the island has changed. Of its once 11,000-plus residents, only 3,000 now remain. Everyone knows everyone else, corruption is rife, and new ideas often come to nothing, owing to the inflexible attitudes of a handful of powerful and influential families. On occasion, Vernaire regrets having returned home. Yet, she says, the volcano has given her a gift: "It has taught me to be adaptable. I can survive anywhere, provided I have food and shelter. That's perhaps the difference between us islanders and Europeans: the ever-present danger makes us resilient and able to survive."

© zVg

Karin Wenger

Karin Wenger

Karin Wenger was South Asia and South-East Asia correspondent for Radio SRF from 2009 to 2022, based in New Delhi and Bangkok. She published three books about her time in Asia. Since last summer, she has been sailing the Caribbean with her partner and writing about forgotten topics and world regions. More information is available at www.karinwenger.ch or www.sailingmabul.com

Global, Opinion

An excess of neutralities

29.09.2022, International cooperation

Corona, climate and conflict are now exacting their price: the UN observes that for 90 per cent of all countries, the "Human Development Index" will decline for 2020 or 2021. During the global financial crisis, just one in ten countries was affected.

© Parlamentsdienste 3003 Bern

The view of Andreas Missbach, Director of Alliance Sud

Cassis, Pfister and Blocher[1] – all three gentlemen are vying to score points with the adjective they use to qualify the n-word. Before we come to the adjective, the noun. Switzerland's neutrality was vital while neighbouring countries remained at war. This was so at the time of the Franco-German War of 1871, and even more so during the First World War, when the country was riven by differing sympathies with the warring parties.

During the Second World War, neutrality notoriously went hand-in-hand another element – that of profiteering from business with the warring parties. Up to 1944, Swiss firms supplied enormous quantities of military materiel to Nazi Germany. During the war years, the situation could still have been described as an emergency, but the business dealings continued thereafter, as neutrality morphed into a fig leaf. "Neutrality", meaning "we do business with everyone and do not care about sanctions", was one of the three factors (together with the financial centre and tax legislation) that propelled Switzerland to global dominance as a commodity trading hub.

As a non-UN member, Switzerland has not adopted UN sanctions, including those imposed on Rhodesia (today Zimbabwe) or apartheid South Africa. Mark Rich, the godfather of Swiss commodity trading, whose firm became Glencore and whose “Rich boys” established companies like Trafigura, described his oil deals with the racist regime in southern Africa as his "most important and lucrative business". But the grain traders on the shores of Lake Geneva also profited from the USA's grain embargo against the Soviet Union and stepped into the breach, although ideologically and practically, Switzerland was by no means neutral during the Cold War.

Now to the adjectives: Ignacio Cassis' "cooperative neutrality" would have put the profiteering into perspective, in that it would have cemented the new status quo created by the Russian invasion (EU sanctions are being adopted). Yet the Federal Council rejected the Federal President's adjective.

Gerhard Pfister's "decisionistic (concept of) neutrality" is less clear. To go by his interview in the Le Temps newspaper, "human rights, democracy and the free expression of opinions" keep profiteering in check. According to an interview with the Tamedia newspapers, it is more about the values of the "western economic and social model", in other words, "rule of law, security of private property and social welfare". Pfister has also failed with respect to a specific matter; in the Council of States, his party The Centre rejected the proposal that Switzerland should also be able to impose its own sanctions.

Christoph Blocher's "integral neutrality" favours a return to unbridled profiteering. He once defended this approach against the critics of apartheid. The “Working Group on Southern Africa” (ASA), which he founded and chaired, fulminated against sanctions and provided South African right-wing politicians and military officers with a platform for their inhumane messages. The ASA also organised propaganda trips: "In the footsteps of the Boers".

I would also like to put forward some adjectives, as Switzerland would be best served by neutrality that is "compassionate (refugees) and globally sustainable (human rights before profiteering)".

[1] Ignazio Cassis of the Liberal Party is Federal Councillor, head of the Federal Department of Foreign Affairs and President of the Swiss Confederation in 2022. Gerhard Pfister, member of the National Council, leads the Centrist Party (Mitte). Christoph Blocher is a former federal councillor and éminence grise of the far right xenophobic Peoples Party (SVP).

Share post now

global

The Alliance Sud magazine analyses and comments on Switzerland's foreign and development policies. "global" is published four times a year (in german and french) and can be subscribed to free of charge.

Opinion

The gendered impact of mining

13.06.2023, International cooperation

What happens when mining companies enter communities and start mining? Who benefits and who suffers?

Women push wheelbarrows onto the stockpile of a coal mine at the Duvha coal-fired power station, east of Johannesburg.

© Denis Farrell / AP Photo / Keystone

A report was commissioned by Fastenaktion in 2022 on the gendered impact of mining on workers and mining communities. Using a gender lens, and focusing on Mtubatuba in South Africa, the report maps the differentiated impact of mining as experienced by those who work and live around mine sites.

In Somkhele, where one of South Africa’s largest open-pit anthracite coal mines (Tendele) is located, people’s lives are characterised by dispossession, removal and displacement from ancestral lands, violent demolition of homes, exhumation of ancestral graves, unsympathetic reburials that ignore rituals and culture, and disregard for the dead and ancestors. Crops and livestock are dying because water, soil and air are contaminated. This has led to a displacement of livelihoods and people’s sense of identity. Grazing fields are disappearing as the mine expands and marks communal land as private property. Catastrophic environmental destruction is evident and undeniable after every blast at the open-pit coal mine, as the entire village is enveloped by coal smog, which disrupts social routines in Somkhele.

The environmental destruction is generalised across the villages, as evidenced by contaminated and destroyed water sources, vegetation and soil, and is leading to dire food insecurity and poverty. Additionally, toxic dust results in severe and debilitating health challenges for workers and community members. These include respiratory, eye and skin diseases, affecting both young and old. Parents talked about their children having sore and watery eyes, painful chests and throats, runny noses, headaches, and sinusitis. Traditional healers, who are the first point of call when villagers are sick, can no longer find the herbs they have relied on for generations to heal the sick. Important local herbs and trees have been cut down to make way for the mine and those still able to grow are covered in coal dust which renders them useless.

Those who get jobs in the mines, mainly men, reported working conditions that are not decent. At Tendele mine, most workers are hired through subcontractors and not directly for the mine. Subcontracting has become a cheaper way of organising production as it relegates some of the responsibilities, including statutory obligations, to third parties who often ignore or undercut legal, labour, health, and safety requirements. Characterising the lives of miners, who are mainly men, is over-exploitation at the point of production, low wages, weak-to-no trade union representation, and health and safety challenges. Workers are often encouraged to chase production targets at the expense of their own health and safety. They face arbitrary dismissals, and most lack proper union representation. Without a voice, their associational and bargaining power and workplace citizenship are compromised.

Women absorb the shocks

The impact of the above working conditions on workers and living conditions in communities is distributed in disproportionately gendered ways. In communities, women disproportionately absorb the shocks and externalities since they are socially and culturally tasked with care work and other domestic tasks such as providing food for the family and ensuring that the household sphere is functioning optimally. In the workplace, by virtue of their numerical dominance, men face the brunt of the negative externalities, as they are at the heart of the exploitative system. Men who contract pulmonary diseases are easily purged by the mine based on precarious work contracts. There is little care for their physical health and their ailing bodies after giving the best years of their lives to the mine, and even less care for their deteriorating “invisible” mental health caused directly by their feelings of uselessness due to their inability to provide for their families. These mental health struggles manifest themselves as violence, but that too is disregarded, as violence and tropes of black masculinity have been treated as synonymous for so long.

The sick men, who often carry transmissible diseases, are sent home to be cared for by wives. This is a huge financial cost to families, who frequently have to sell livestock and redirect family savings towards the sick husband’s health care bills. Wives mend what is broken and pick up the pieces from deteriorating health, feelings of failure due to inability to put food on the table in the context of dispossessed ancestral lands, and self-loathing by the now abandoned former miners. Wives and girl children take care of the now sick former miners, and as they pick up the pieces of their dignity and self-worth, they also pick up the diseases that miners bring with them from working on the coalface. At times, they too fall ill, and the cycle continues, or ends when the miner dies.

The general sentiment from interviews and focus group discussions is that the mine has created or heightened poverty in families that were once self-reliant. Only a handful of political elites, local petit bourgeois – the contractors who have mine tenders, truck and taxi owners – a minority, have benefitted. Even for them, things remain precarious, and the cost they pay through their health, land and graves of ancestors is far higher than what they have been able to eke out through mine contracts. In interviews, we consistently heard people say: “They took our land and gave us R420 000 (less than CHF 20 000), diseases, poverty, and a cleaning job”. This, after giving up or being forcibly removed from tracts of ancestral lands. They asked, “How can the mine take away everything that fed us, and only give one person a contract job?” There is thus a resentment in the community, and it manifests itself in protests directed at the mine. These protests, both at work and in the community, have been marked by violence, intimidation of local activists and the assassination of anti-mining and worker activists.

Global solidarity is critical

In conclusion, while mining has been central in shaping South Africa’s social, economic, and political landscape, in the main, experiences of workers and communities have not been positive. The ‘benevolence’ of mining companies and their public relations machinery, which churns out reports with hyper-positive narratives about the impact of mining on economic growth, has not addressed or prevented harm. People’s rights to life, safety, food, water, housing, culture, and to a safe environment have all been undermined. The environmental, social and cultural impacts require urgent and honest attention from those in power. People need avenues of recourse. The mines and the State, in collusion with traditional authorities, cannot continue without being held accountable for the crimes committed in these communities by mining capital. Global solidarity from like-minded organisations and activists is critical, since many other communities across the Global South are facing similar harm from large-scale, global mining companies.

© Asanda-Jonas Benya

Asanda-Jonas Benya is a sociologist at the University of Cape Town, South Africa, and currently a visiting lecturer at the Graduate Institute in Geneva.

Share post now

Opinion

Providencia: The fear never goes away

17.03.2021, Climate justice

In mid-November, hurricane “Iota” almost completely destroyed the Colombian island of Providencia. Its roughly 5000 residents lost everything, but are not giving up, says Hortencia Amor Cantillo, a direct victim.

The hell in paradise

© Hortencia Amor Cantillo

My husband, my two sons and I have already been through two hurricanes. In 2005 we were hit by hurricane “Beta”; that was nothing in comparison to “Iota”, however. Both times the hurricane struck at night. Of course, we did not know how strong “Iota” would be, we thought it might perhaps be a category 1 or category 2 hurricane. When I realised at 4 a.m. that we were already up to a category 4 hurricane, I was scared, not least of all because the wall of our house was shaking. It was frightening. When you’re struggling with the storm all night, you can’t see the fear on people’s faces, as everything is dark, including the sky. The first impression comes from the destruction and desolation that greets you at dawn. It was like being in a state of shock: you simply cannot believe all that you’re seeing in front of you.

No roof over your head

This hurricane hit my family very hard, above all emotionally. We felt disoriented – so great was the destruction that we had no idea where to begin. Moreover, our tourism business – the small inn (posada) that was our livelihood and what kept us alive – had been destroyed. The Children and Youth Centre which I ran was also largely destroyed. I am now trying to see how to pick myself up again.

For the moment we still have four guests at our house, we were 27 people at first, or five families in one house. Most of them have somehow organised themselves and cobbled together small dwellings with sticks and sheets of metal on the lots where their houses once stood. Learning to live with other people, to display solidarity and share things with one another was also a new experience for us. It is one thing to greet one another from time to time and to visit people, but quite another to live together with them. We have started preparing one large meal for everyone, with each person contributing what they can. I thank God that we were able to help others. Many people have lost everything, literally everything. Many were left with just the clothes on their backs. Many had taken refuge in small toilet houses made of concrete, some of which were at least able to withstand the storm. Shortly after the storm the government sent camping tents, but they were of poor quality. It has rained a lot and the water would seep into the tents from underneath. They are okay for a few days, but some people have now been living in them since November 16th. They are complaining, as everything is wet. Those who got tents set them up on the concrete foundations that remained where their houses once stood, or in their toilet outhouses. It is very hard on those who have lost everything. The storm swept everything away. Even the roof on the second floor of our house was blown off completely; we have found one or two pieces, but no-one knows where the roof is now. Still, we have been lucky.

Fortune in misfortune

An NGO arrived about a week after the hurricane and began distributing one warm meal per day. Its personnel are stationed in different parts of the island. Here in San Felipe they are based in the Catholic Church. At midday they ring the bells and people gather to get lunch and a fruit. They are still here, but they too are finding it tough, as the food is prepared on San Andrés Island and brought in by air to Providencia. They are now trying to find a way to prepare the meals here on the spot and so get around the complicated logistics, which sometimes means that meals do not arrive on time. So far we have their support, for which I thank God.

The first thing being done by the government is restoring the roofs of those houses that are still standing; many roofs have been donated by private persons. They are now being installed with the help of the army, the national police, the merchant navy and air force, civil defence and the Red Cross. They are all here and helping with the reconstruction. But the process is very slow, especially for those whose houses were completely destroyed and are being rebuilt last. For those whose houses are still partly standing, things are moving a little faster, but we do not know how long this will take. Meanwhile, they are all making their studies and plans. We are doing everything to speed things up. Naturally, there are things we need help with. We will need machines to rebuild the beaches, and there is a lot of debris precisely along the shore, which we cannot remove by ourselves.

We intend to stay here

Nature will take longer to recover from this. There are some very big trees here – we call them “cotton trees”. I have been living on this island for the past 26 years and I always see these huge trees with their thick trunks, they must be very old. Many of them have now been uprooted altogether, some are still standing but have lost all their branches and leaves. It will take many years for these trees to grow back. The coral reefs too have been destroyed, and their rehabilitation will take a very long time.

The hurricane season comes around every year from July to the end of November. The fear is ever present, but we think it is unlikely that another hurricane of this magnitude will hit us. And we are not the only ones in such a situation. The coasts of the USA, Mexico and Nicaragua are also at risk from hurricanes. We know that it can happen again and again. I agree with my husband that from now on, every house must have a section made of concrete where people can take refuge. But disasters, earthquakes and the like are happening all over the world.

Someone asked me if I would like to leave Providencia. I said no, as there is some kind of danger everywhere. It is sad and it hurts, but we are here and we intend to stay here. For us, Providencia is a little paradise and we will do everything to build back our paradise.

Share post now

Opinion

Switzerland must step up its game post-Glasgow

06.12.2021, Climate justice

The final declaration of the UN Climate Conference is by no means the end of the story – with the climate crisis intensifying and Switzerland's climate budget about to run out. From Glasgow Stefan Salzmann (Co-Chair of Climate Alliance Switzerland)

Tuvalu's foreign minister did his COP26 statement like no other by speaking behind a podium at sea, standing in knee-deep water.

© EyePress via AFP

Summer hail and rain in Switzerland, heatwave in Canada, fires in Greece and Russia, drought in Iran; and in August the science-based red alert in the latest report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Climatologists state clearly that the scale of anthropogenic global warming has been unprecedented for many centuries, if not millennia. The frequency and intensity of heat extremes and heavy precipitation, and of agricultural and environmental droughts will increase and they will recur more and more often in combination. Changes already apparent today will intensify and become irreversible. Every 10th of a degree increase in the global average temperature makes a difference – especially for the world’s poorest and most vulnerable.

The new report published by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) in October, which compares the goals of the Paris Agreement with the promises made, finds that the targets submitted by countries are taking us towards global warming of 2.7 degrees. At the same time, UNEP also writes that still not enough funding is being provided for adaptation in poor countries: what is needed is up to 10 times what the industrialised nations are making available.

The will is there – but no-one is laying out a roadmap

In the circumstances, the United Kingdom organisers of the 26th World Climate Conference have shown much good will. New global initiatives were announced every day for the first week of the conference. "Global Coal to Clean Power Transition", "Stop Global Deforestation" or the "Green Grids Initiative" are but a few. A euphoric International Energy Agency reckons that this could put us on track to global warming of just 1.8 degrees – if all the promises are kept. This is precisely the problem: there is no implementation plan for any of these initiatives. The countries going along with the promises are the very ones which up to 2020 had failed to provide the climate funds promised back in 2009. Besides, should a country like Brazil sign up to the deforestation initiative, it would indeed be a glimmer of hope, but in terms of realpolitik, perhaps more of a death knell for this ambitious plan. Like all other ambitious plans, this one too leaves implementation up to voluntary political action by individual countries.

And Switzerland?

Switzerland too is under pressure: after even the small step of the revised CO2 Act proved too much for most citizens in June 2021, the delegation led by the Federal Office for the Environment went to Glasgow with no legal basis. On this occasion yet again, all negotiations on additional climate funding were blocked. At first glance the reasons are understandable – rich emerging countries should also help provide climate financing and it is not acceptable for China and Singapore to pass themselves off as developing countries, and to want to pay nothing. But this kind of argument from one of the world’s richest nations is of no use to those whose livelihoods depend on these decisions, i.e. the poorest and most vulnerable around the world. For them, stalled talks, irrespective of who is responsible, spell hardship, suffering and precarious survival strategies.

Loss and damage

The livelihoods of many are at stake, and for some, they have already been destroyed. In the technical jargon, “loss and damage” describes the irreversible problems stemming from climate warming: in other words, climate impacts that outstrip the adaptive capacity of countries, communities and ecosystems. When a family loses its home to rising sea levels, it is lost for ever. Such loss and damage is already occurring today and will be amplified with every temperature rise of one-tenth of a degree. This is why civil society has made this issue the top priority in Glasgow.

Switzerland’s climate budget almost used up

The fact that Switzerland is one of the richest countries with a history of emitting large quantities of greenhouse gases is not the only reason why it would be appropriate to help others that have already suffered damage. In September, social ethicists from 10 church institutions held discussions about remaining CO2 budget that is compatible with a climate justice. On the basis of scientifically proven data, they calculated the share of the gigatonnes of CO2 still globally available that would corresponds to Switzerland, should it elect to act in a climate-friendly manner. In so doing, the social ethicists did what climate science cannot: they weighted and interpreted model calculations in moral terms. The upshot was that the remaining climate-compatible amount of CO2 would be used up by the spring of 2022. This is further proof that the Federal Council’s strategy of targeting net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 no longer has anything in common with justice.

What next?

Occasions like the Glasgow climate conference should be seized by official Switzerland to demonstrate that our country takes justice seriously. Providing funds for other countries is one of the easiest ways to do this: funds for mitigation and adaptation additional to development credit lines. And additional funds for loss and damage that has already occurred. The groundwork for such negotiating mandates is laid domestically, during the preparatory phase. The same applies to national climate targets, which will need to be more ambitious, including for Switzerland, if the targets of the Paris Climate Agreement are to remain within reach. The debates on the indirect counterproposal to the Glacier Initiative and the upcoming relaunch of the revision of the CO2 Act are the last opportunities before it is too late. We need a net-zero target by 2040 at the latest, a linear reduction pathway there and we must be resolute in phasing out fossil fuels.

Share post now

Opinion

The solution does not grow in rice paddies

06.12.2022, Climate justice

With Ghana, Switzerland is implementing the world's first foreign climate protection project under the Paris Climate Agreement of 2015. But this project misses the mark.

© Dr. Stephan Barth / pixelio.de

The climate circus on the African continent has taken down its tents again. Admittedly, there is, at last, a fund for loss and damage. However, the way it will be structured and, most importantly, how it will be financed, are still very open questions. On balance, the upshot of COP27 is: “It’s good that we have talked about it”, so let us now talk about something else.

At the very start of the conference, the New York Times threw a spanner in Switzerland’s works by publishing a critical article about its carbon offsets abroad. The first project to be implemented under a bilateral climate protection agreement between Ghana and Switzerland was unveiled five days later. In order to offset the Federal Government’s emissions, rice farmers in West Africa are to cease permanently flooding their fields. The intention is to reduce methane emissions. Implemented by the UN Development Programme, this project may well make perfect sense, but it misses the most significant challenges of reducing greenhouse gases in Africa.

Some 600 million people in Africa have no electricity, and two-thirds of their power is currently produced from fossil fuels. Yet it is possible to provide decentralized, reliable and CO2-free electricity. The money from the trade in indulgences in the form of emission certificates would best be dedicated to that purpose.

In the run-up to the conference, the UN’s Trade and Development organization pointed to an even bigger challenge: one-fifth of the countries in Sub-Saharan Africa depend on oil exports. Other countries could also be exploiting fossil deposits. The Democratic Republic of the Congo, for example, is currently putting new concessions up for auction; and as long as the USA and Australia continue to produce natural gas and coal, respectively, the North lacks any legitimacy whatsoever to preach self-denial to this extremely poor country. “Leave it in the ground” is a recommendation with a price, and Africa is unable to pay it.

It will also take enormous sums of money if today’s exporters are to forego their principal source of income. This would make it all the more crucial for the remaining oil revenues to be used for this transition, but a substantial portion of it has so far been squandered through corruption, embezzlement and mismanagement. Switzerland is in part responsible here, as borne out yet again by a court ruling in early November: Glencore employees were criss-crossing Africa with suitcases full of cash in order to obtain oil at bargain prices. Commodity trading needs to be regulated such that Switzerland ceases to bear any part of the responsibility for the resource curse. This could offer Switzerland a way of providing Africa with much more funding than by purchasing emission certificates derived from rice paddies.

Share post now

Global, Opinion

The power of education

22.06.2021, International cooperation

"I want women to be heard and to no longer be treated as the properties of men", says Joyce Ndakaru, Gender Officer at Haki Madini.

I grew up in a very traditional Maasai Boma, where all decisions were taken and all responsibilities assigned by men. As a young girl, before the age of 6, I had to milk cows and goats, collect firewood and sweep the house, wash the dishes and also cook some food. From about 8 years to 12, one is considered to be a growing girl that will become a mother soon, so one’s responsibilities also increase as one prepares to become someone’s wife. Girls can then start herding cows and start cooking heavy food and collecting more firewood.

Boys on the other hand don’t milk, they don’t cook or sweep, because they are men. But they do look after the goats. They also collect stones and play that the stones are their cows or they play that they are getting married. In that way, they prepare themselves to become powerful people, who own lots of cows. Girls do not have time to play, it is actually considered a shame if a girl is seen playing. As a child, I did not know anything about the rights of children, so I did not think it was unfair. I only came to realize that much later in life.

I was lucky to be able to go to school. I was actually not taken to school because I was loved, but rather as a punishment, as I was not very good at milking or looking after the goats. I was afraid, that the cows would kick me and whenever I had to herd goats, I always lost a few. I also did not like collecting firewood and went to collect it crying. So my father decided to take me to school in order to be disciplined. He thought I would learn to be a better child, because I would have to follow the teachers’ orders and I would receive corporal punishment. But I really liked school and I was actually performing very well. I was always the best in my class from class 3 up to class 7. My father however never intended for me to go on to Secondary School, he thought Primary School would be enough punishment. By the time I finished Primary School, he had also received many offers for me and he had actually chosen a man that was older than himself (about 60 at the time) to marry me.

I was going to get married, when I think the grace of God actually passed into my life. There is a school known as the Maasai Girls Lutheran Secondary School and they were going around Maasai villages, looking for poor Maasai girls at risk to be married off. They invited me and some other Maasai girls from other villages to sit a written exam. I did very well in the exam and was the only one among the group to be selected to go to Secondary School. They had actually planned to choose more than one girl, but I was the only one who passed the exam. However, the others did not fail because they were not smart enough, but because their families had advised them not to do well. I was actually also advised to make sure I would not pass the exam and I had promised my family that I would just write down illegible things, but in the end, I did not keep my promise, while the other girls kept theirs.

After passing that exam, the teachers asked me, if I thought that my parents would allow me to go secondary school. I felt very uncomfortable and told them in a very low voice: “No, I don’t think my parents would allow me to go. Can you help me?” So, they came with me to my village to tell my family that I was chosen to go to secondary school. I was very scared and thought that my parents might kill me, because I remembered a time, when the primary school teachers had asked me to write down my young sisters’ name, so she could be enrolled in school. When my father found out what I did, he punished me and chased me out of the house. My sister was never allowed to go to school and now leads a very tough life.

But the teachers and I that day told my family that I had passed the exam. My family was very angry with me and told me that I was a disgrace, that I was disrespecting my community and abandoning my culture. I tried to plead with them, but in the end my father said that I was no longer his child and they ripped all my Maasai ornaments off me and let me go. My mother could not say anything, because she is a woman and has no power.

So, I went to school with nothing and stayed there without any visits for several years. I could also not visit my family, since my father would surely marry me off, if I went home. It took him a long time to accept that I was not coming home, but after a few years he came to visit me at school one day. He told me that they had decided that I could finish secondary school and asked me to come home during the school breaks, promising that they would not marry me off. Even though he kept his promise and did not marry me off, my family tried everything to discourage me from going to school and to make school look like hell. They were telling me that my class mates all had several children by now, that they all had their own homes and families and that I was lost and did not even know my culture. Although, they could read my name in the newspaper every year, as I came out top of the class year after year, they kept up the pressure and did not support me financially in any way.

Thanks to an anonymous sponsor, I was able to finish Secondary School. After that, I did not know what to do, as it is expected that after Secondary School, your family helps you through university. But again, I was very lucky, as Reginald Mengi, the former owner of IPP News, was a guest of honour at our graduation ceremony. During his speech, he asked, how many of us would like to go to university to study journalism. Me and some others raised our hands, not knowing what he had in mind. He took down our names and then paid for our university fees. With that help he took me to where I am today - a degree holder, a program officer with over 9 years experience gained working for different NGOs in Tanzania, a gender activist and a responsible mother and role model for my family and the Maasai community, especially for Maasai women.

Today, my village and my family are all proud of me. My former class mates, who are grandmothers by now, because they were all married at 12 or 13, admire me. Back then, they were laughing at me and telling me that I was disrespecting my parents, but now they all wish that they could also have gone to school. They tell me that I am very lucky to be able to look after myself, while they depend on their husbands for everything. They even tell me that I look much younger than them, because of the lifestyle I have. Many are now sending their kids to school, taking me and some others who have gone far, as role models and telling their kids to be like us. Even my dad is proud of me now. I send money to support him,my siblings and other family members. Although none of my father’s other daughters have been allowed to go to school after me, some of my brothers are sending their girls to school.

Slowly, things are changing, although many of the girls who go to school now still end up getting married and leading a traditional life, but if you look at them, you can nevertheless see some differences. They are smart, they look after their children better and cook healthier food. Some men are realizing the value of having an educated wife. I just wish for all Maasai to be enlightened and take their boys and their girls to school and to realize that allowing their daughters to go to school is not a bad thing and does not remove them from being Maasai. I also dream ofone day opening my own NGO called “Maasai Women’s Voice” to raise the voices of marginalized Maasai women, who have been oppressed for many years. I want to establish a platform, where their contributions and their voices will be appreciated. I want women to be heard and to no longer be treated as the properties of men.

Share post now

global

The Alliance Sud magazine analyses and comments on Switzerland's foreign and development policies. "global" is published four times a year (in german and french) and can be subscribed to free of charge.

Global, Opinion

Constant flux

24.06.2021, International cooperation

The only constant in life, as Heraclitus taught us, is change. Yet, it was almost 13 years ago now that I took up my first position at Alliance Sud. For family reasons, the time has now come to say farewell.

© Daniel Rihs / Alliance Sud

In 2008 when I assumed responsibility for area of «tax policy» at Alliance Sud, Finance Minister Hans-Rudolf Merz still believed that Switzerland’s banking secrecy was as immovable as the Gotthard Massif. Nothing stood in the way of tax evaders and corrupt dictators in developing countries who wanted to conceal their fortunes in Switzerland. Then came the global financial and economic crisis, which sounded the death knell for many of the Millennium Development Goals that should have been attained by 2015; on the other hand, however, it gave fresh momentum to the fight against tax evasion.

Suddenly, even the powerful industrial countries were keen to crack down on tax offenders. They urgently needed more government revenues to pay for their multi-billion bailout packages for banks. For its part, however, Alliance Sud had to fight on for years until Switzerland finally extended automatic information exchange in tax matters to developing countries. It is still campaigning against the deplorable incentives available to multinational corporations to shift their profits from poor countries to Switzerland, largely untaxed.

When in 2015 I succeeded Peter Niggli as Director of Alliance Sud, the Sustainable Development Goals were just taking the place of the Millennium Development Goals. Through the 2030 Agenda the rich industrial countries committed to a course of action geared not merely towards short-term national interests but to the long-term well-being of humanity and the planet. This makes it all the more surprising today to witness the degree of exasperation with which some Federal Councillors and Parliamentarians greet NGOs that get involved in Swiss policy in order to promote respect for human rights and the protection of the environment.

Then, as now, Alliance Sud was a political irritant. We should not be impressed by the latest tit-for-tat responses to civil society for taking an active interest in development policy. Now more than ever, socially equitable and environmentally sustainable world development calls for a Switzerland that aligns all policies coherently with this goal – from foreign to economic policy, and including climate policy. The Alliance Sud team, member organisations and allies will continue to advocate for this cause in the future, with dedication, indefatigable commitment and the power of the right arguments. I take this opportunity to thank them from the bottom of my heart for the wonderful cooperation we have had.

Share post now

global

The Alliance Sud magazine analyses and comments on Switzerland's foreign and development policies. "global" is published four times a year (in german and french) and can be subscribed to free of charge.

Global, Opinion

Reimagining Africa

01.10.2021, International cooperation

The world is jaded by the multiple planetary emergencies upon us. These emergencies are compounded by the widespread failure of leadership at both the public and private sector levels.

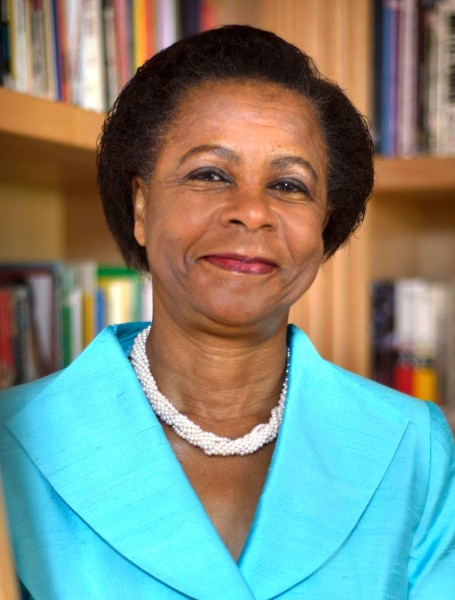

Co-President of the Club of Rome and Co-Founder of Reimagine SA.

© Mamphela Ramphele

Scientific knowledge is proving inadequate to the task of getting humanity to reimagine new ways of being human. Reimagination requires going deep into oneself. Such reimagination demands of us to be prepared to unlearn our extractive value systems and learn anew from nature that we are part of an interconnected and interdepended web of life. As indigenous cultures across the world teach us – we have to become indigenous again and function within the rhythm of nature’s wisdom. Becoming indigenous again would enable humanity to emerge from these emergencies with a new human civilization – one in harmony with nature.

Young people all over the world are slowly but surely rising to the challenge of leadership in the face of the failures of their parents and leaders. Global movements such as Fridays for the Future, Extinction Rebellion, Rainbow Warriors, and Avaaz have taken it upon themselves to shape the future they desperately wish to see emerge.

Young people in Africa are also rising to the opportunities of embracing the wisdom of their ancestors. Africa’s wisdom is that it is a land of abundance – there is enough for all if we share equitably. The value system of Ubuntu enables all to share in the prosperity generated through collaborative work. There are no free riders in Ubuntu.

A significant proportion of the more than 600 million 15-49 year old Africans, are building innovative solutions to address the multiple challenges they face across a multiplicity of contexts. They are turning scarcity of provision of old technologies in telecommunications and financial services, into opportunities to create abundance. Cell phones and online financial services are leveraging the estimated annual flows of remittances (estimated at 44bn USD) to establish cheaper and more reliable connectedness between the diaspora and the home base.

Africa is also slowly dismantling the colonial education models that have held her youthful population hostage to education systems that alienate them from their rich cultural heritage. Colonial education models have mentally enslaved Africans for generations, making many to continue to believe in white supremacy and black inferiority. It is this mental slavery that continues to undermine Africa’s ability to leverage its abundance to generate shared prosperity.

We are witnessing the creation of new education models such as the seventeen year old Leap Math and Science Schools in South Africa, that are helping young people to free themselves from this mental slavery and to embrace the wisdom of Ubuntu. The healing impact of interconnectedness and interdependence results in self-confidence and restored dignity and self-respect. The outcomes are spectacular in the poorest most broken slum areas of South Africa from which they come. Leap graduates become leaders in their broken communities as teachers, engineers, civil society, political actors and many other professionals. These outcomes belie the poverty the world sees in Africa. Young people see abundance, and are the abundance of Africa.

Africa as the largest continent (landmass equal to Europe, China and USA combined) with the largest resource base (60% arable land; 90% of mineral deposits, sun and rain in abundance; and the most youthful population of 1,4bn) needs to find a new development model. Such a model has to be framed within the Ubuntu philosophy to leverage this rich resource base through collective action that unleashes the talents and creativity of its youthful population.

The world stands to gain from an Africa pursuing a more sustainable regenerative socio-economic development model. Such an Africa would be able to share its abundance in a more equitable way. Africa’s youthful population, freed from mental slavery and affirmed as innovative energetic global citizens, would provide the critical skills and creativity that the rest of the aging global community would need. The world needs to co-invest with Africa in an accelerated regenerative socio-economic development that leverages Africa’s land mass for food security. Drawing on Africa’s indigenous knowledge of organic agriculture and her rich marine food systems would ensure secure healthy food for all.

Africa’s minerals that are fuelling the world economy, including the newfound rare earths essential for electronics, need to be mined in a sustainable way. Extractive mining practices are not only damaging the African landscapes, but undermining the wellbeing of her people. Sustainability of the flow of the benefits of mineral wealth for the entire global community requires radical transformation from extractive approaches to regenerative ones.

The world need to seize the COVID pandemic and climate change existential crises as opportunities to learn anew how to work together as a global community. This would ensure that we shift from degenerative approaches to regenerative ones that promote sustainable wellbeing for all. This entails changing excessive consumption patterns to wiser choices to enable us stay within planetary boundaries. It also entails that we embrace nature’s wisdom that there can be no Me without We. Humanity is inextricably interconnected and interdependent.

My reimagined Africa in 50 years’ time is that of a continent that has reclaimed her heritage as the cradle of humanity and of the first human civilization, modelling nature’s intelligence to ensure that everyone contributes their best to the wellbeing of all in the entire ecosystem. Africa would then offer the world a model of how to learn anew to become fully human.

Share post now

global

The Alliance Sud magazine analyses and comments on Switzerland's foreign and development policies. "global" is published four times a year (in german and french) and can be subscribed to free of charge.

Opinion

Fifty years of advocacy for solidarity

05.10.2021, International cooperation

Alliance Sud has been working for a Switzerland of solidarity for 50 years. Our President Bernd Nilles looks back - and into the future.

Bernd Nilles, President of Alliance Sud and Director of Swiss Catholic Lenten Fund

© Fastenopfer

Fifty years of Alliance Sud, 60 years of Swiss Development Cooperation (SDC), 60 years of Swiss Catholic Lenten Fund, 75 years of HEKS/EPER – a few decades ago the mood was overwhelmingly upbeat regarding global responsibility. Is there cause for celebration today, or perhaps not, considering the number of unsolved problems in the world? We are constantly facing new challenges and crises – including the climate crisis and the considerable time pressure it entails.

When in August 1971 – shortly after the introduction of women's suffrage – our founding fathers set up the Swiss Coalition Swissaid/Swiss Catholic Lenten Fund/Bread for Brethren/Helvetas, they presumably had no idea that the journey was to last five decades and beyond. The initial focus was on informing the Swiss public about the situation in developing countries and about global interconnections; development policy was only added later, in the 1980s. The early realisation that long-term transformation would necessitate changes in the North and South was a far-sighted one, and the successful unification of Swiss aid agencies with a coordinated and credible voice in development policy matters has been a historic accomplishment on the part of Alliance Sud.

I would like to take this opportunity to thank everyone who helped shape and make this story possible. Alliance Sud has initiated a series of policy changes over these past 50 years; it has played a part in expanding and further enhancing development cooperation and has been an unflagging advocate for a Switzerland that practises solidarity.

Alliance Sud too is ready to evolve. We set this in train in 2021 and will accordingly be strengthening our focus on advocacy and hence our impact by that means. This seems imperative in the light of persisting global challenges and injustices, especially where Swiss policies bear some share of the blame. Besides, the business sector continues to wield disproportionate power and influence, a fact that leads not infrequently to policy decisions that are detrimental to people and environment. It must be legitimate in this connection to ask why Federal Councillors are now calling for the business sector to be more politically engaged, while at the same time attempting to reduce civil society's room for manoeuvre.

What is good for the business sector is not automatically good for Switzerland and the world. Good and sustainable policy decisions also need to take the voices of citizens and civil society into account – we have underscored this repeatedly over the past 50 years. We intend to continue to be actively involved and to stand up for global justice through expertise, dialogue and debate.

Share post now