Share post now

global

The Alliance Sud magazine analyses and comments on Switzerland's foreign and development policies. "global" is published four times a year (in german and french) and can be subscribed to free of charge.

Impact Investing

21.03.2025, Financing for development

Advocates of impact investing portray it as one way to help fund both the Sustainable Development Goals and climate targets. In a recent study, Alliance Sud took a closer look at this contribution, which to date remains rather limited.

Few investments are made in the poorest countries, as they are considered too risky. A farmer in Guerou, Mauritania, uses solar panels to irrigate his pastures. © Tim Dirven / Panos Pictures

It is no secret that Switzerland aims to become a leader in the realm of sustainable finance. At the heart of "sustainable" finance is impact investing, with a twofold ambition, namely, ensuring "market-based" financial returns, while also helping to resolve global social and environmental challenges. Laid out for the first time in 2007 by the Rockefeller Foundation, this approach has since gained many public and private followers in the international financial system; their shared objective is to "mobilise" private capital in order to attain the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Some even see this as a way of cushioning the cuts to Official Development Assistance (ODA) budgets. Yet, there is a yawning financing "gap" for achieving those goals. According to UN Trade and Development (UNCTAD) based in Geneva, developing countries are grappling with an annual funding gap of more than USD 4000 billion. Of this amount, some USD 2200 billion are needed to fund the energy transition alone.

To put things into perspective, at the end of 2023, Swiss banks – the leaders in cross-border wealth management – were managing some CHF 8,392 billion. Hence the somewhat simplistic question: what portion of this wealth could be invested in developing countries to fund the SDGs?

In its “Sustainable finance action plan”, the Federal Council aims to extend access to impact investing to include private capital, going beyond just private foundations and family offices, and this "on a large scale" in order to fund projects that make a "measurable and credible contribution to the aims of sustainability". In parallel, it also aims to create new economic outlets for Switzerland's asset management industry. In other words, impact investing is to be brought out of its niche and made accessible and attractive to institutional investors, including pension funds, which are seeking, or must secure a financial return acceptable to the market.

In parallel, Switzerland's international cooperation funds – which Parliament reduced in December last, let us recall – are being deployed, as part of blended finance, to reduce investment risks and so render impact investing financially more attractive. The hope is that this risk reduction will have a "demonstration effect" and attract the aforementioned institutional investors on a larger scale.

To examine the plausibility of these expectations, Alliance Sud used a recent study to present Switzerland's impact investing market, that is to say impact investing managers based in Switzerland and deploying capital in developing countries. This market comprises some 18 players managing almost USD 15 billion in assets. Of this amount, some USD 11 billion comprises "private" assets, in other words investments in shares and bonds issued by private enterprises in developing countries – in contrast to "public" enterprises, which are listed on the stock exchange.

To put this figure into perspective, this amount represents less than 0.6% of the global volume of "sustainability-linked investments" (according to the definitions applied by the Swiss Sustainable Finance association), or 0.116% of the total volume of assets under management (AuM) by Swiss banks at the end of 2023 (the roughly CHF 8400 billion mentioned above).

Countless European banks are involved in low-risk, high-return projects such as the Cerro Dominador solar power plant in the emerging nation of Chile. © Fernando Moleres / Panos Pictures

This market is highly concentrated, with its three leading players – responsAbility, BlueOrchard and Symbiotics, now all foreign-owned – controlling 80%. In regional terms, these investments are concentrated mainly in Latin America and the Caribbean (24%), and also in Eastern Europe and Central Asia (20%), given the relative political and economic stability and an investment-friendly environment. Sub-Saharan Africa, on the other hand, receives only 13% of overall investments, while the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) receives a mere 2%, reflecting less attractive investment conditions and risks perceived as too high in these regions.

One half of impact investing is concentrated in 10 countries. India heads the list with 15% of overall exposure, followed by Cambodia, Georgia, Ecuador and Vietnam. All told, 35 countries account for 85% of the investments (taking into account only countries with at least 1% exposure). As of 2025, only 14 of these 35 countries are priority countries for Swiss international cooperation. In income terms, one half of them consists of upper middle-income countries. Only four are least developed countries (LDCs), i.e., Cambodia (6%), Bangladesh (2%) – countries from which the SDC has announced its withdrawal as of 2025 following budget cuts – Tanzania (1%) and Myanmar (1%).

The Swiss impact investing market is also highly concentrated in terms of sectors. Microfinance dominates the market, accounting for about half of total assets under management. The two sectors of microfinance and SME development account for more than 80% of investments, reflecting their financial performance. The sectors of food and agriculture as well as climate and biodiversity receive significantly less investments – with 10% and 4% respectively – despite their substantial financial needs. The "social sectors", including housing, water supply, healthcare and education, together attract less than 2% of the capital. This is due mainly to the fact that these sectors generally do not offer attractive financial returns and are often managed by governments as public goods.

The Swiss impact investing market therefore tends to be concentrated in regions and sectors that offer lower risks and higher financial returns. This reflects a broader trend towards "safe" investments, which does not necessarily address the more urgent challenges of sustainable development. In its conclusions, the Alliance Sud study underlines the fact that impact investing obviously cannot by itself offset the deficit in funding for achieving the SDGs. It is therefore crucial to prioritise the mobilisation of domestic resources, the fight against illicit financial flows and the maintenance of substantial official development assistance for the poorest countries.

Share post now

global

The Alliance Sud magazine analyses and comments on Switzerland's foreign and development policies. "global" is published four times a year (in german and french) and can be subscribed to free of charge.

Private climate finance

05.12.2024, Financing for development, Climate justice

Many people favour greater use of private funding to cover current and future contributions from the countries in the North to those in the South in their fight against climate change. A stocktake by Laurent Matile

Correcting inflated expectations: An initiative launched by Barbados' Prime Minister Mia Mottley to promote climate finance for developing countries has scaled back its demands on the private sector. © Keystone / AFP / Brendan Smialowski

"The numbers that are thrown around about the potential of green capital mobilization are illusory. [...] There is a lot of piffle in this area." These were some of the remarks made by Lawrence H. Summers, former US Treasury Secretary and President Emeritus of Harvard University, in wrapping up a panel discussion in Washington D.C. last October.1

At COP29 in Baku, which ended on 24 November, a new climate financing goal was agreed at the last minute: developed countries have pledged to triple funding, from the previous target of USD 100 billion per year to USD 300 billion per year by 2035. This is far too little in view of the needs of developing countries, which are estimated to total USD 2,400 billion a year. In a nebulous formula, it was further agreed to ‘secure the efforts of all actors’ to increase funding for developing countries, from public and private sources, to 1.3 trillion dollars a year by 2035.

Despite not being central to the COP29 agenda, mobilising private climate finance is still considered the silver bullet by many public and private players. The definition of "climate finance" does not in fact specify what portion must be covered by public and/or private funding. This vagueness has spawned much uncertainty as to the source of the funds being allocated to climate, and allows governments ample leeway in meeting their commitments. And there is great temptation to use private funds to fill the public funding gap.

The fact is that since the conclusion of the Paris climate agreement in 2015, many public and private players – the ones Lawrence Summers has in mind – have stepped up their efforts to advocate for the design of "innovative financial instruments" that benefit from public subsidies and invariably pursue the same aim: that of de-risking in order to "catalyse" private investments, whether for the climate or for sustainable development. And this credo is not about to disappear. In the back of their minds, numerous delegations, including Switzerland, are thinking that whatever the final amount owed by each developed country, it will be possible to secure a substantial part of it by "mobilising private capital".

Let us consider for a moment the current state of climate finance in developing countries. The latest OECD2 figures show that:

The OECD recalls (time and again) that "a number of challenges may affect the potential to mobilise private finance" to combat climate change in developing countries. These include the general environment that may be enabling (or not) for investment in beneficiary countries, the fact that many climate projects are not profitable enough to attract large-scale private investment; or, the fact that individual projects are often too small to obtain significant commercial funding.

Few ideas seem as hackneyed as the hope that a few billion dollars in public funds will be able to mobilise trillions in private investment for sustainable development and climate protection. This credo is increasingly being challenged, and not just by non-governmental organisations.

The Bridgetown Initiative 3.0, for example, has reassessed its expectations regarding the mobilisation of the private sector. Launched in 2022 by Mia Mottley, the charismatic Prime Minister of Barbados, the third version of this initiative was published in late September. It aims to rethink the global financial system in order to reduce debt and improve access to climate finance for developing countries. While Bridgetown 2.0 called for over USD 1.5 trillion per year to be mobilised from the private sector for a green and just transition, version 3.0 has scaled back the amount being requested to "at least USD 500 billion".

In the light of the outcomes in terms of the volumes and characteristics of private finance mobilised to date, a number of conclusions can be drawn:

Position of Alliance Sud

First, Alliance Sud is calling for most of Switzerland's "fair share" to international climate finance to be provided through public funding – with a balance between funds allocated to mitigation and those allocated to adaptation. Second, the call is also made for private funding mobilised through public instruments to be counted towards Switzerland’s climate finance only if its positive impact on people in the Global South can be duly demonstrated.

1 CGD Annual Meetings Events: Bretton Woods at 80: Priorities for the Next Decade, Washington D.C., October 2024.

2 Climate Finance Provided and Mobilised by Developed Countries in 2013-2022, OECD 2024.

Share post now

global

The Alliance Sud magazine analyses and comments on Switzerland's foreign and development policies. "global" is published four times a year (in german and french) and can be subscribed to free of charge.

Study

10.12.2024, Financing for development

Impact Investment has gained popularity, particularly in Switzerland, a country known for its financial system and its aspirations for sustainable finance. As impact investing is often presented as a panacea for development challenges, Alliance Sud’s study takes a critical look at its effectiveness, its limitations and the extent to which it can contribute to sustainable development.

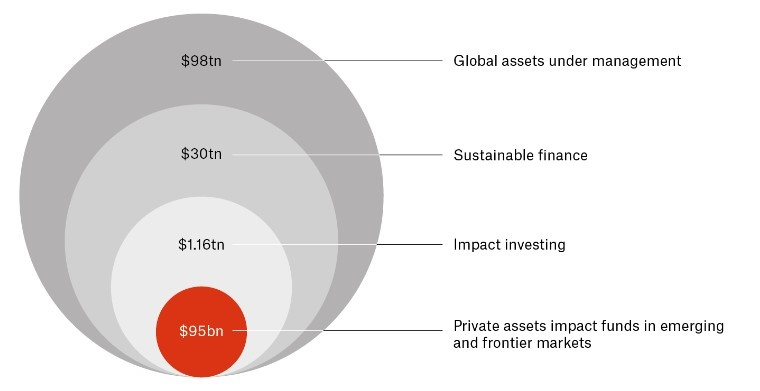

Impact investing, while growing, remains a niche market globally,

particularly in developing countries. Source: Tameo 2023.

Share post now

REBUILDING UKRAINE

03.10.2024, Financing for development

The Federal Council wants to allocate to the Swiss private sector 500 million earmarked for reconstruction in Ukraine. This certainly does not serve the interests of Ukraine's economy and enterprises.

Large Ukrainian steelworks such as Zaporizhstal have been attacked or occupied and are barely able to maintain their production volumes. © Keystone/EPA/Oleg Petrasyuk

Speaking at the Ukraine Recovery Conference (URC) in Berlin on 11 June last, Federal Councillor Ignazio Cassis laid out Switzerland's commitments: "First, the private sector plays a key role in the reconstruction process. Switzerland is promoting sustainable framework conditions and ensuring that small and medium-size enterprises (SMEs) can function and remain competitive". In cooperation with the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), Switzerland announced its support for a new mechanism to protect private investments against war risks, and its intention to join an alliance to support SMEs. One therefore had reason to believe that the Swiss Foreign Minister's intention was to give priority support to Ukrainian companies and the Ukrainian economy.

Two weeks later, however, on 26 June, the Federal Council announced that "Switzerland's private sector should play a key role in Ukraine's recovery efforts". The Federal Council plans to allocate CHF 500 million for that purpose over the next four years, that amount coming from the budget of CHF 1.5 billion earmarked for Ukraine in the International Cooperation Strategy 2025-2028. Almost the entire sum will be transferred from bilateral development cooperation funds at the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) to the State Secretariat for the Economy (SECO). The "Ukraine country programme" as a whole will be managed by Jacques Gerber, currently Councillor of State for the PLR in the Canton of Jura, who will be attached to the General Secretariat of the FDFA as Delegate for Ukraine, and will report directly to Federal Councillors Cassis and Parmelin.

As far as we are aware, the SECO plans comprise two phases. First, support is to be given to Swiss companies already operating in Ukraine to enable them to create or maintain jobs. To this end, the federal government must cover the risks faced by those companies, for example, through financial assistance or insurance solutions. The justification given for using international cooperation funds is that the projects of companies being supported must include a "development component", for example vocational training programmes. So far nothing is clear, but some potential beneficiaries are being mentioned, including the glass manufacturer Glas Trösch. Moreover, some measures are meant to incentivise Swiss companies not yet active in Ukraine to invest there. That could crowd-out Ukrainian SMEs and companies.

The second phase, in which SECO envisages giving preference to the Swiss private sector in general, is even more problematic. Ukraine would receive money from Switzerland which it could then only use for procurement from Swiss companies. This tied aid is at odds with best practices of international cooperation, WTO provisions, and with Swiss law on public procurement. There is no legal basis for that practice, and it would therefore have to be created in the coming months. For the Federal Council, an international agreement with Ukraine would suffice, while the Foreign Affairs Committee of the Council of States has called for a specific law. During its winter session, the Parliament will take the final decision on the package as a whole in the context of the International Cooperation Strategy. The decision by the Federal Council to grant preferential treatment to Switzerland's private sector is obviously not consistent with the promises made in Berlin, however. The fact that Ukraine is free to decide for itself what it needs from Swiss companies is not a convincing argument. In an emergency, you will accept a supermarket voucher even if it is disadvantageous to your own village shop, which you should be supporting.

What Ukraine needs is support from the international community – which should include Switzerland – for its economy and its companies, the backbone of which comprises small and medium-size enterprises (SMEs) – some 90% – which are showing exceptional resilience despite the uncertainties of the war. A recent study by the London School of Economics1 has found the Ukrainian economy to be remarkably resilient, but that growth prospects will remain weak for as long as the war continues. Ukrainian producers are losing domestic market share to international competitors that are not operating in wartime conditions. This represents a loss to Ukraine that gives cause for concern and illustrates that the country’s relatively open economy (especially vis-a-vis the EU, through the Association Agreement) is ill-suited to wartime conditions. In the circumstances, increased State purchases of goods and services (through public procurement) from Ukrainian private enterprises is a crucial tool for boosting the resilience of Ukraine's wartime economy by supporting production capacity and employment while laying the groundwork for future recovery and reconstruction.

Partners, including Switzerland, must therefore support a "localisation offensive" to guarantee and build national capacities. They should support the Ukrainian Government's "Made in Ukraine" subsidy programme, which is designed to boost national production. They should set the example by making local content stipulations a condition for providing financial aid to Ukraine, so that aid going to Ukraine is spent in Ukraine. Efforts should also be made to favour technology transfer to the Ukrainian economy. Not only would this boost fiscal receipts, but thanks to increased exports, also foreign exchange receipts, both of which will be needed to repay the reconstruction loans granted by the international community (mainly the EU).

Moreover, Western countries should encourage cooperation between their enterprises and Ukrainian ones for goods production (through joint ventures or consortiums, for instance), using mechanisms that insure against war risks, and providing favourable funding. In the short term, that could boost the resilience of Ukraine’s wartime economy and, over the medium-to-long term, facilitate its integration into global value chains. The measures in the first phase of Switzerland's plans would therefore be meaningful, if the appropriate framework conditions were met.

Reconstruction planning should take account of the green transition, which would both make Ukraine's economy sustainable and facilitate alignment with the EU's Green Deal. Investing in clean energy would be indispensable, as would be efforts to decentralise energy production (Ukraine has a large number of small electric power plants), which renders the industry less vulnerable to Russian strikes. Foreign partners and investors should help Ukrainian enterprises that are lacking in capabilities and human capital to deploy cutting-edge technology, including zero-emission technologies. SECO's plans could also contribute to this.

There is nonetheless an appreciable shortage of funding for modernising Ukraine's industries and for reconstruction, including in the construction materials and metalworking industries, and for decarbonising their structures, some of which date back to the Soviet era. Creating a Ukrainian development bank could provide the long-term capital needed for such re-industrialisation projects. Western partners, including Switzerland, should support Kiev in its quest for funds and provide the requisite guarantees for the large-scale funding of Ukrainian companies.

Ukraine's burgeoning raw materials sector demonstrates the need for both increased funding and a targeted industrial policy. In Berlin, EU representatives hailed Ukraine's huge reserves of ‘critical raw materials’, which the European Commission considers to be crucial to the European economy. Ukraine is said to have 22 of the 34 minerals identified as essential for ensuring the EU's ‘strategic autonomy’, or even ‘European sovereignty’. A Ukrainian development bank could help national companies to become players in this emerging sector and maximise value creation in Ukraine.

It is clear to Alliance Sud that some measures in the first phase of SECO's plans could be wise, if they create jobs, facilitate technology transfer – especially "green" technology – and entail partnerships with local companies, and if it is ensured that promoting Swiss companies does not mean crowding out Ukrainian ones. There is an urgent need for transparent reporting on specific plans so that their utility or their undesirable effects can be assessed. Switzerland's aid should nevertheless focus on support for the local private sector and the Ukrainian economy. That would require funding first and foremost; Switzerland would do better to use existing multilateral channels instead of going it alone.

The second phase, which is designed solely to secure a "piece of the reconstruction cake" for the Swiss export sector, would clearly run counter to the interests of the Ukrainian economy. Yet, a Ukrainian economy with long-term stability is more beneficial to Switzerland than full order books for some companies in the short term. These plans should therefore be stopped. Clearly, these activities are only marginally in line with Switzerland's international cooperation priorities and should therefore not be funded from the international cooperation budget.

1 A state-led war economy in an open market. Investigating state-market relations in Ukraine 2021-2023. LSE Conflict and Civicness Research Group, 4 June 2024.

Share post now

global

The Alliance Sud magazine analyses and comments on Switzerland's foreign and development policies. "global" is published four times a year (in german and french) and can be subscribed to free of charge.

AFGHAN FUND

01.10.2024, Financing for development

While billions in Afghan currency reserves are being managed in Geneva, civilians in Afghanistan are suffering from the indescribably precarious economic situation in the country. Shah Mehrabi, Co-chair of the Board of the Afghan Fund, is now calling for targeted disbursements.

The quantity of Afghani banknotes in the country fluctuates greatly. Banknote dealers are omnipresent in Kabul. © Keystone/EPA/Samiullah Popal

Three years after the Taliban came to power, Afghanistan is teetering on the brink. The rights of children and women are being violated: the latter have become virtually invisible in public spaces – sports facilities, hammams, beauty salons and parks are off-limits for them. Their education ends with primary school, and there is strict gender segregation at work places. Media and opposition forces are being repressed. One-half of the population now live in poverty and 90 per cent can no longer meet their basic food needs.

"The economic situation is extremely precarious, mainly because of restrictions on the banking sector, the disruption of trade and commerce, the weakening and isolation of public institutions, and the virtual absence of foreign investment and financial support from foreign donors in sectors such as agriculture and manufacturing", the United Nations warned earlier this year.

Meanwhile, millions of dollars being managed from Geneva by the Fund for the Afghan People (Afghan Fund) remain unused. The Fund was set up two years ago to manage the foreign currency reserves of the Afghan Central Bank (DAB); those reserves were frozen when the Taliban took power in August 2021. At the time, the Federal Reserve Bank in New York was holding 7 billion USD of these reserves. Another 2.1 billion USD are now in Europe and other countries. To prevent the money deposited in the USA from being frozen by the victims of September 11, President Biden suggested that half that amount should be placed abroad. The sum of 3.5 billion USD was therefore deposited in an account with the Bank for International Settlements located in Basel, and a foundation for managing the funds was created in Geneva, namely, the Afghan Fund (see also here). Its purpose is to manage the monies and to return some of it to the DAB in accordance with strict specifications. At the end of June 2024, the assets, including interest, were worth 3.84 billion USD.

Now, two years on, not a single cent has been repaid. Why is this? "First, there is some misunderstanding of the rules, in that this money is not meant for humanitarian purposes, but to stabilise the financial system", says Shah Mehrabi, one of the two Afghan Co-Chairs of the Board of the Fund, speaking by phone from the USA. The professor at Montgomery College in Maryland points first to macroeconomic aspects: currency reserves are assets held by central banks in foreign currency for the purpose of ensuring a country's solvency and influencing its monetary policy. The aim is to protect central banks from a rapid devaluation of the national currency. These reserves play a key role in stabilising the exchange rate, boosting the trust of citizens, providing liquidity for the banking system, and meeting import costs.

"The DAB has now announced a contraction of the money supply, i.e., the amount of money in circulation", he adds. "Why is that? The freezing of the reserves is one contributing factor. When there is less money in circulation, people have less purchasing power, economic activity declines, and this in turn impacts prices and exchange rates. This is precisely what we are witnessing in Afghanistan: enterprises cannot raise funds to invest, which leads to dwindling demand for goods and services. They therefore continue to lower prices so as to incite people to buy. The result is deflation, which is just as harmful to an economy as inflation".

"We have accomplished a lot", he continues. But what exactly? Regarding the governance of the Fund, he confirms that a solid structure has been created: statutes have been adopted and a Board of Trustees appointed, which will report transparently on the management of the assets. He himself forms part of the Board, along with Anwar-ul-Haq Ahady, former DAB Director and Ex-Finance Minister of Afghanistan, Jay Shambaugh, a representative of the US Treasury Department, and Ambassador Alexandra Baumann, Head, Prosperity and Sustainability Division of the FDFA. Decisions are made unanimously, which implies that each member has de facto veto power.

The Board of Trustee members elaborated a proactive investment strategy and tasked a consulting firm with working out compliance and audit measures. This is designed to prevent money laundering and the funding of terrorism. The post of Executive Secretary was created, a communications strategy was drawn up and an international advisory panel established.

"The measures we took were part of the requirements that have to be fulfilled before any disbursement", Shah Mehrabi continues. "My view is that the conditions now exist for targeted disbursements to stabilise the exchange rate, print banknotes and pay for imports. They should be made in small tranches however, as injecting too much money would cause inflation."

He adds that, despite significant challenges, the Afghani has remained stable, particularly against the U.S. dollar, thanks to the DAB sound monetary policies. These include foreign exchange auctions, tighter controls on smuggling, increased exports, humanitarian aid inflows, and remittances. “However, this stability has also led to deflation due to global price drops and the Afghani's appreciation. Currently, the deflation rate stands at -9.2%, slightly better than the previous -9.7%. To further ease deflation, the Central Bank may need to reduce dollar auctions and increase the circulation of Afghani banknotes”, he concludes.

The political situation is rather complex, however. The international community does not recognise the present regime. Legal and diplomatic resources are limited, which diminishes the Fund's ability to negotiate. Yet there are no international sanctions on the DAB. The Taliban, for their part, do not recognize the Afghan Fund. They want their money back. At any rate, says the economist, something is being done with a portion of the assets frozen by the USA – in stark contrast to the 2.1 billion USD frozen by the EU.

"We cannot let the Afghan people suffer. It is now in the interests of everyone to proceed actively with these disbursements. Humanitarian aid alone will not solve the problem. Long-term development is the key. We must act", concludes Mehrabi, whose mandate for the Afghan Fund was extended in September for a further two years, as was that of the other members of the Board.

Like most countries, Switzerland, too, has no current plans to relaunch long-term development cooperation in Afghanistan, but is at least returning to the country. "The SDC (Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation) will open a humanitarian office in Kabul in the autumn of 2024", its spokesman Alain Clivaz confirms. "It will be housed in the premises of the former cooperation office, which was closed in 2021. The humanitarian office there will comprise four members of the Swiss Humanitarian Aid Unit (SHA). The SDC Team is responsible for implementing, supporting and monitoring projects funded by the SDC."

The FDFA Spokesperson points out that the security situation in Afghanistan is still a complex one and entails considerable risks to all activities in that country. He affirms nonetheless that the SDC is closely monitoring developments in the situation and has a widely-supported security arrangement for its staff, which is making this return to Kabul possible.

"At the technical level, the SDC Office contacts Taliban representatives whenever this is necessary to project implementation", he concludes.

Alliance Sud views a presence in Afghanistan as important, even though humanitarian aid alone cannot replace a functioning economy. Switzerland must ensure that the monies being managed by the Afghan Fund are repaid to the DAB with all due care. This must be done so that the Afghan people are not penalised several times over: on the one hand, by a repressive regime and sanctions, and on the other, by being ostracised by the international community.

Share post now

global

The Alliance Sud magazine analyses and comments on Switzerland's foreign and development policies. "global" is published four times a year (in german and french) and can be subscribed to free of charge.

International Cooperation Strategy 2025-2028

21.06.2024, International cooperation, Financing for development

The Federal Council adopted the long-awaited Dispatch on the 2025–2028 International Cooperation Strategy in mid-May. In it, the Council stands by its policy of funding aid to Ukraine at the expense of the Global South, thereby ignoring the outcomes of the public consultation.

© Ruedi Widmer

In terms of content, the Government makes no significant headway and relies on tried and tested themes and implementation approaches in the 2025–2028 Strategy. And this in a world which, according to the Strategy, is more fragmented, unstable and unpredictable. In this context, the Federal Council opts for more flexibility – its word of the moment. We need flexibility to cope with the current crises, said Federal Councillor Ignazio Cassis at the press conference. But anyone reading the Strategy will soon realise that flexibility merely means funding the entire CHF 1.5 billion in aid for Ukraine from the International Cooperation (IC) budget, and that the amounts for other countries and programmes will therefore be "flexibly" cut back.

At the press conference on 10 April on the Bürgenstock Peace Conference and aid to Ukraine, Federal Councillor Ignazio Cassis had already spoken of the continuous reallocation of resources in international cooperation. Resource allocation was a strategic, dynamic process and not a static approach. Such a dynamic approach can certainly be useful, for example, when it comes to flexibly interlinking the three pillars of international cooperation, namely, humanitarian aid, development cooperation, and peace building (the term 'nexus' is also used). In any case, the boundaries between these areas are often fluid.

International cooperation that constantly shifts its resources between different regions and countries cannot build serious, long-term partnerships. Yet, this is precisely what is needed to operate effectively and efficiently. It takes trust and long-term commitment, in other words, relations that are forged and preserved through development cooperation programmes. Or, as Federal Councillor Cassis said during a dialogue with NGOs in 2022: "Reliability, trust and predictability". If Swiss international cooperation becomes a geopolitical pawn, it will lack the networks and staffing it needs on the ground. The war in Ukraine has marked a turning point, but this ought not to become a reason for Switzerland’s international cooperation programme to jettison what has been built up and jointly achieved with partner countries over many years.

In deciding to fund aid to Ukraine from the international cooperation budget, the Federal Council is dealing several blows at the same time. First, it is a refusal addressed to the Global South, which for years has been calling on wealthy countries to meet the internationally recognised target of 0.7% of gross national income for official development assistance (ODA). Under the Federal Council's proposal, Switzerland's ODA (not including asylum costs) will be 0.36% in 2028. Where, then, is the much-vaunted humanitarian tradition when it is needed?

Another rejection is directed at those who took part in the consultation process. An overwhelming 75% majority of the organisations, parties and cantons that responded to a relevant question stated expressly that aid to Ukraine must not be at the expense of other IC regions and priorities such as Sub-Saharan Africa or the Middle East. No political party supports the funding of Ukraine's reconstruction from IC, except for the Swiss People’s Party (SVP), which, to go by its party programme, wants to dispense with development cooperation altogether. Unfortunately, in the wrangling over federal finances, the Parliament has so far failed to identify ways of implementing this, that could attract majority support.

Foreign observers have not failed to notice that Switzerland is relaxing with its comfortable and lucrative special status as a neutral country, while failing to play a substantial enough role in Ukraine's defence, whether in the form of military or humanitarian support. With a debt ratio of 17.8% of gross domestic product, Switzerland cannot credibly explain to the international community its inability to come up with additional funds for Ukraine. At the same time, through their funding proposals for upgrading the army and for a 13th OASI pension payment, the SVP and the FDP (The Liberals) are peddling the idea that Switzerland can simply renege on its international obligations.

Switzerland is thus increasingly isolating itself and becoming internationally irrelevant. Goodbye mediator role, goodbye humanitarian tradition and reliable partner. The Federal Council has correctly read the signs of the times, but has opted for the path of isolation. That is why only the Parliament can now act to remedy the situation and bring about a change of direction for Ukraine and the Global South.

Share post now

global

The Alliance Sud magazine analyses and comments on Switzerland's foreign and development policies. "global" is published four times a year (in german and french) and can be subscribed to free of charge.

Global, Opinion

21.06.2024, Financing for development

A careful reading of the International Cooperation Dispatch 2025–2028 sent by the Government to the Parliament left us somewhat aghast. But the big shock came at the beginning of June, when the IC also came under scrutiny in the Council of States as part of the discussion on the army dispatch.

© Parliamentary Services / Franca Pedrazzetti

A careful reading of the International Cooperation Dispatch 2025–2028 sent by the Government to the Parliament left us somewhat aghast. As we already knew that the national government intends to fund support for Ukraine entirely at the expense of the Global South, the cause was one telling detail. In the German version, the Government stated the following about the decline in the ODA ratio (of which we were already aware, regrettably): "This is due to the fact that the growth of GNI [gross national income, i.e., the economy] has significantly outstripped that of the funds allocated to IC, as a result of the financial measures taken in connection with the debt brake." Whaaat? Can it be that in times of financial crises and epidemics, all those that can afford it, do contract debt to pump-prime their economies, while people in Federal Berne think that reducing government debt via the debt brake will lead to economic growth? But then came clarification: it was merely a translation error from the French version.

We were truly aghast on June 3rd as we followed the deliberations of the Council of States. First came the rejection of a motion that would have provided the increase in army spending by 2030 so desperately wanted by the conservative male majority, at least on an exceptional basis and in combination with exceptional funding for aid to Ukraine. But immediately thereafter, that majority decided to increase the army budget for weapons purchases by 4 billion, while simultaneously slashing development cooperation funds by 2 billion. A frontal attack on IC! (One annoying detail about the unique link forged in this manner and on this scale between the army and international cooperation is that it constantly brings military metaphors to mind...).

This, despite the statement by the newly created State Secretariat for Security Policy itself, that "A direct military threat from a land or air attack on Switzerland is unlikely in the near-to-medium term." Threats from cyber-attacks, for example, have nevertheless intensified. The following statement by the Government in the security policy report had either been forgotten or had never been taken on board: "It [foreign-policy] helps to strengthen international security and stability by offering good offices, helping to promote peace, standing up for international law, the rule of law and human rights, tackling the causes of instability and conflict through development cooperation and providing humanitarian aid to alleviate the plight of civilians." After all, expecting that even the notion of human security may have landed with the majority in the Council of States is truly asking too much.

But the battle to salvage IC is not yet lost, the counterattack is on, and we will not surrender! Please excuse the military metaphors.

Share post now

global

The Alliance Sud magazine analyses and comments on Switzerland's foreign and development policies. "global" is published four times a year (in german and french) and can be subscribed to free of charge.

Article, Global

21.03.2024, Financing for development

In October 2023, the OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC) took a decision that has largely escaped public notice. It is about including "private sector instruments" in development financing, and could hold far-reaching implications for the poorest countries in the South.

© Christina Baeriswyl

The way of measuring development funding has been a topic of discussion since its inception. While donor countries in the North wish to be seen as being as generous as possible, countries in the South want the biggest possible share of the funds to go where it is most needed. This is the backdrop to the current debate on the inclusion of public contributions for loans and various types of investment in enterprises located in countries of the South.

In February 2016, and as part of the process of "modernising" the definition of Official Development Assistance (ODA), members of the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) agreed for the first time on principles by which to account for Private Sector Instruments (PSIs). These instruments include loans to enterprises, equity investments, mezzanine financing1 and guarantees.

At the time, however, DAC members failed to agree on the rules that would govern the inclusion of PSIs in ODA, in accordance with the principles agreed. Provisional reporting methods were therefore put in place in 2018. As PSIs represent just 2-3 per cent of total ODA, the solution was deemed acceptable while the DAC worked to find a more permanent solution. In October 2023, a new permanent agreement was reached on PSIs, with potentially far-reaching consequences for development financing.

Since the introduction of ODA in the 1960s, one of its key principles has been that of concessionality. Under this principle, development funds are exclusively grants, or take the form of preferential loans. The OECD-DAC decision of October 2023 supplanted this principle and redefined ODA. The new rules require that when private sector instruments are included, evidence must be presented regarding the role of the funds allocated to these instruments in adding value, whether financially or in terms of content and development (see “The three definitions of additionality”). DAC member countries are expected to provide information on the type of additionality of the PSIs they use. This is mandatory.

But the DAC itself regrets that the data provided so far has been sketchy and that the additionality reports submitted are "incomplete and unconvincing". Yet, solid reporting on additionality is the key to ensuring that DAC members effectively allocate scarce ODA resources where the needs are greatest, and where they can be most impactful.

For a PSI activity to qualify as ODA, it must provide additionality at the financial level or in value and development terms:

In the absence of adequate additionality reporting, however, one can only make presumptions about, rather than demonstrate the added value of PSIs. In other words, without this information, there is the risk that ODA could be artificially "inflated" by creative accounting practices, and this would increasingly water down the definition of "development assistance". On a seemingly positive note, as of 2026, information provided on the additionality of PSIs will undergo special examination by the DAC Secretariat "to enhance the integrity of ODA". It is to be hoped that these verifications will make for greater transparency.

According to a Eurodad study, between 2018-2021, a total of USD 20.6 billion was reported as PSIs, representing 3 per cent of total ODA. By themselves, the four main European countries (UK, EU, Germany and France) account for 80 per cent of the total of PSIs from DAC members. Switzerland ranks 11th, with 0.7 per cent of the total.

Eighty-five per cent of the total was channelled through Development Finance Institutions (DFIs), including the Swiss Investment Fund for Emerging Markets (SIFEM) in Switzerland. The respective DFIs of the four major European donors – British International Investment (BII) in the UK, the European Investment Bank (EIB/EU), the Kreditanstalt für den Wiederaufbau (KfW) and the Deutsche Investitions- und Entwicklungsgesellschaft (DEG) in Germany, and France's Proparco – account for 91 per cent of all PSI ODA reported by these DAC members. Some of these DFIs have seen their portfolios double in the space of ten years, and the amount of DFI activity is expected to grow further in the years ahead.

Source: OECD-DAC Creditor Reporting System 2023.

These development finance institutions have a profitability mandate and therefore invest preferably in countries and regions with a lower risk profile and more secure profit expectations. As the figure above illustrates, between 2018 and 2021, most of the private sector instruments were invested in upper middle-income countries (59 per cent), followed by lower middle-income countries (37 per cent). Only 4 per cent of PSIs were allocated to least developed countries (LDCs). This shows that only marginal amounts of the development funds managed via PSIs reach the countries most in need.

Switzerland reports some CHF 35 million as ODA in the form of PSIs, which include capital payments of CHF 30 million per year to SIFEM, plus a few other instruments (less than CHF 5 million). SIFEM specialises in the long-term funding of SMEs and other "fast-growing" enterprises, in order to stimulate economic growth and create jobs.

A distinction must be drawn between PSIs and "amounts mobilised from the private sector", in other words, all private funding mobilised through public development finance interventions, regardless of the origin of the private funds. These funds are not part of ODA, but may be included in the broader indicator of development financing – total official support for sustainable development (TOSSD).

In its latest edition, the 2023 DFI Transparency Index – which analyses the activities of the 30 leading DFIs with assets totalling USD 2000 billion – SIFEM occupies a very low position in the transparency rankings! At the close of 2022, SIFEM's investment portfolio amounted to USD 451 million, and was allocated almost entirely to middle-income countries (MICs). More specifically, 62 per cent was invested in lower middle-income countries and 34 per cent in upper middle-income countries. Low-income countries (such as Ethiopia and Malawi) accounted for just 3 per cent of the investment portfolio. As of the same date, only 42 per cent of the portfolio was invested in priority countries for Switzerland's international cooperation.

We are witnessing a critical period where wars, the fallout from the coronavirus pandemic and the growing impacts of climate change are plunging millions of people into poverty. Donor-country resources are remaining flat or diminishing, and are therefore being used to cope with a growing number of crises and wars. This raises the question as to whether the development of private sector instruments, the vast majority of which are allocated to better-off developing countries, is the ideal path for Switzerland's international cooperation (IC). The current database is not sufficient to allow for a definitive assessment of the effectiveness of these instruments. But the current geographical distribution is such that we question whether private sector instruments are contributing to the constitutional mandate of IC – i.e., to assist those in need and combat poverty in developing countries and regions, and to favour the most disadvantaged population groups. These instruments should therefore not play a pivotal role in Switzerland's international cooperation, also in the future. But it is much more crucial to ensure that the modernisation process does not further dilute the principal benchmark for development financing, i.e. ODA, and that Pandora's box is closed once again.

1 The OECD defines mezzanine financing as instruments relating to types of financing that fall between an enterprise's senior debt and equity, displaying features of both debt and equity.

Share post now

global

The Alliance Sud magazine analyses and comments on Switzerland's foreign and development policies. "global" is published four times a year (in german and french) and can be subscribed to free of charge.

Article, Global

10.12.2020, Financing for development

The 2030 Agenda rests on what is hitherto the most ambitious funding strategy for sustainable development. Is it realistic to think it possible to raise trillions for the sustainable development goals?

A worker controls beer production in Beni, Democratic Republic of Congo. It is questionable whether private investors also have poverty reduction in mind. © Kris Pannecoucke / Panos

In addition to public funds, private funding sources – domestic and foreign – are deemed indispensable. This is even viewed in some circles as the ideal way of meeting the funding shortfalls. More specifically, these private funds encompass private investments as well as philanthropy and remittances.[1] In its International Cooperation Strategy 2021-2024, the Swiss Government advocates for diversifying and scaling up cooperation with the private sector; it envisages deploying Official Development Assistance (ODA) funds as a means of raising "additional private funds" for sustainable development.

The Blended Finance approach in particular is one of the financial vehicles intended to attract private resources for sustainable development financing. While it has generated very high expectations, the outcomes to date have been rather modest.

Let us try to achieve some clarity on the basis of five questions:

1. Blended Finance: What is it about?

There is no universally accepted definition of Blended Finance. The underlying idea, however, is for funds and other resources (personnel, expertise, political contacts, etc.) from bilateral and multilateral official development aid to be deployed as a "levers" to mobilise private sector investments for development cooperation.

2. What are the currently existing models?

In practice, Blended Finance works as follows: private investors generally aim for a financial return commensurate with the investment risk, in other words, a risk-adjusted return. The higher the risk – real or perceived – the higher must be the hoped-for return to offset that risk.

In public financing (bilateral or multilateral), there are essentially two approaches to attracting private investors to projects that (a priori) do not meet risk-based return expectations. Under one approach, the investment risk to the private investor can be reduced (de-risking); under the other, the potentially yield accruing to the private investor can be increased.

In general, risk reduction through instruments such as guarantees or first loss capital is applied to projects that seem profitable enough but carry a considerable risk of default or loss of value. The yield may be increased by granting preferential loans to the investor to offset certain project costs, or through an equity stake. These are ways of offering an investment incentive to private investors. Another possibility is technical assistance to reduce certain transaction costs (in the form of feasibility studies, for example).

Both approaches – reducing risk and increasing return – are tantamount to subsidising private investors from official development assistance funds.

3. How does this benefit the poorest?

This is the key question. The Federal Act on International Development Cooperation states that such cooperation is meant to support "primarily the poorer developing countries, regions and population groups" (Article 5.2). To this day, however, there is little evidence of any benefit from such blended finance in the poorest countries.

Blended Finance has indeed grown exponentially, but has so far bypassed the least developed countries (LDCs). The bulk of Blended Finance transactions have gone to middle income countries (MICs), where the main beneficiaries are the sectors with the highest return on investment – i.e. energy, financial services, industry, mining and construction. Sectors like education or health are hardly involved.

4. What are the risks?

Blended Finance carries the following risks:

The Alliance Sud Position paper "Blended Finance – Mischfinanzierungen und Entwicklungszusammenarbeit" (in German and French) offers an in-depth analysis of the potential, limits and risks of blended finance and makes some recommendations.

5. What are the alternatives?

The question generally arises as to whether and under what circumstances the use of Blended Finance and partnerships between players from official development cooperation and private enterprises could fulfil the (high) expectations placed on them.

It should be recalled in this connection that the Addis Ababa Action Agenda (AAAA) provides for the mobilisation of domestic public resources as a priority area of intervention for development financing and that combating illicit financial flows is indispensable in this context. Moreover, in developing the private sector, priority should go to local enterprises, especially micro, small and medium-size enterprises (MSMEs) – especially businesses run by women – and to domestic financial markets.

Blended Finance can thus be just one among several financial instruments with which to implement the 2030 Agenda.

[1] Over recent years, remittances – money sent back to their home countries by workers living and working abroad – have skyrocketed. For numerous developing countries, they currently represent the most substantial source of foreign financing, outstripping even Official Development Assistance (ODA) and Foreign Direct Investment (FDI).

A mere 6 per cent of the USD 157 billion in private funding raised between 2012 and 2017 – or USD 9.4 billion – went to least developed countries (LDCs). Furthermore, Blended Finance projects in LDCs tend to attract less private funding.

Some 55.5 per cent of these funds go to the energy and banking sectors, while just 5.6 per cent go to projects in the social sectors.

The modest level of Blended Finance activities in LDCs underscores the fact that like private financing, this form of mixed funding falls on fertile ground in those regions with the smallest obstacles to the mobilisation of capital.

Blended Finance projects have often succeeded in mobilising additional funds, but these have generally had little impact on poverty. It is more often the case that owing to inadequate monitoring and reporting as well as to a lack of transparency, the development impact is not known. All Blended Finance endeavours ought to be based on co-determination by the respective countries. Projects that are guided by the priorities of developing countries and take local and national players on board are more likely to achieve sustainable outcomes.

Source: Financing for Sustainable Development Report 2020. Inter-agency Task Force on Financing for Development.

Share post now

global

The Alliance Sud magazine analyses and comments on Switzerland's foreign and development policies. "global" is published four times a year (in german and french) and can be subscribed to free of charge.

Article, Global

22.03.2021, International cooperation, Financing for development

In implementing the International Cooperation Strategy 2021-2024, the SDC plans to scale up its cooperation with the private sector and strike up new partnerships. How is this impacting developing countries?

Foreign Minister Ignazio Cassis visits a tourism education institute during his trip to Africa in February 2021.

© Foto: YEP Gambia

Working with the private sector is nothing new in the framework of Switzerland’s international cooperation, whether in the activities of the State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (SECO) or the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC).[1] In accordance with Sustainable Development Goal No. 17 enshrined in the 2030 Agenda, that of entering into partnerships in pursuit of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), Swiss international cooperation had already increased involvement with the private sector during the period 2017-2020.[2] So far, however, that cooperation had never been framed within an SDC strategy. This will now change, at least in part.

Published in January 2021, the “General Guidance on the Private Sector in the context of the International Cooperation Strategy 2021–24” lays out the basic principles governing SDC activities in connection with the private sector and outlines various forms of cooperation with private sector players, as well as the associated challenges and opportunities.

Considering that the private sector makes “the largest contribution to global poverty reduction and sustainable development” – especially as pertains to jobs, taxes and “innovative products that increase living standards in developing countries”[3] – the document states that the Federal Department of Foreign Affairs (FDFA) as well as the Federal Department of Economic Affairs, Education and Research (EAER) plan to step up cooperation with the private sector under the International Cooperation Strategy 2021-2024 and the Federal Council’s new 2030 Sustainable Development Strategy.

In this connection, the SDC points out that in addition to official development assistance (ODA) and domestic tax revenues, the 17 Sustainable Development Goals can only be achieved if “private sector investments are successfully mobilised.” The private sector is therefore considered by SDC as “part of the solution” for reaching the global development and climate protection goals.

For the SDC, private sector involvement in sustainable development is focused on the following four areas of activity: (1) Economic policy frameworks: this includes promoting the rule of law as well as responsible business conduct and sustainable investment. (2) Promotion of local companies in the priority countries for Swiss international cooperation, especially small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). (3) Private Sector Engagement (PSE): this entails engaging in partnerships with private sector players from Switzerland and other countries. And last but not least, (4) Public procurement. This area of activity encompasses SDC contracts awarded to private sector players (at home and abroad), which must meet more stringent sustainable development criteria in the future.

According to the SDC, the third area of activity, private sector engagement (PSE) encompasses ways in which Swiss international cooperation can engage with “established" private sector players that “consistently promote” sustainable development. The SDC states that such private sector players – in both the real economy and the financial sector – can contribute to poverty reduction and therefore make interesting partners for international cooperation. They include large companies and multinational enterprises, SMEs, social enterprises, impact investors and grant-making foundations. Each of these categories has its own “specific strengths”. In this connection, the SDC also mentions, for example, NGOs and academic institutions as possible implementation partners.

As stated in the “SDC Handbook on Private Sector Engagement”, the SDC plans, over the medium term, in other words during the implementation of the International Cooperation Strategy 2021-2024, to increase engagement with the private sector as well as the financial volume of its PSE portfolio. In addition to “traditional” PSE approaches, “new financial instruments” are to be developed, whereby the volume of public-private cooperation can be increased also in least developed countries (LDCs) and in fragile contexts.

Although the document mentions that the setting of a quantitative growth objective is not meaningful, it does note that currently some 8 per cent of all SDC-funded projects (bilateral activities and global programmes) entail partnerships with the private sector. Based on a combination of various factors, it is estimated that over the long run, some 20-25% of all SDC operations could be implemented in collaboration with the private sector, in both the bilateral and multilateral spheres. If we take as a baseline value the 2020 volume of spending of CHF 165 million for the roughly 125 existing partnerships, the volume could rise to almost half a billion in annual spending over the long term.

It should be recalled that the International Cooperation Strategy 2021-2024 makes no provision for the increase of the respective credit lines for the funding of these partnerships, but provides for them to be paid for with funds already earmarked for bilateral development cooperation.[4] This means that the increase in partnerships with the private sector will take place at the expense of other forms of cooperation that have been shown to hold implications for poverty alleviation, more particularly programmes in support of essential public services including education and health. It could also negatively impact other forms of private sector support in developing countries, including the promotion of local SMEs.

It is therefore necessary to ensure the developmental impacts of these partnerships and the relevance of the goals being pursued through this kind of cooperation with the private sector. On this point, the “General Guidance on the Private Sector” nevertheless remains vague, or as it stands, fails to convey any clear idea of how SDC plans to guarantee, under such partnerships, the effective fulfilment of its primary mandate, that of combating poverty in priority countries.

The SDC internal handbook lays out various criteria and modalities for cooperation as well as a complex risk analysis procedure. But as always, the devil is in the detail. The SDC will have to ensure that in creating the partnerships, these criteria and processes are effectively observed by all players and not merely ticked off on a list.

Given the clear trend among the Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) and bilateral donors, the SDC could find itself under pressure to “boost” its PSE portfolio without being able to guarantee that these partnerships are consistent with the core objective of the 2030 Agenda, that of “leaving no one behind”.

[1] See external audit report 2005-2014 on the promotion of employment.

[2] See “Switzerland’s international cooperation is working. Final report on the implementation of the Dispatch 2017–20”, p. 7.

[3] This statement must be qualified in many respects. More on this later.

[4] “In the event that the SDC establishes new forms of cooperation with the private sector, a new budgetary credit line could be created and the requisite funding will be drawn from the ‘Development cooperation (bilateral)’ credit.” IC Strategy 2021-2024, p. 35.

Share post now

global

The Alliance Sud magazine analyses and comments on Switzerland's foreign and development policies. "global" is published four times a year (in german and french) and can be subscribed to free of charge.