Share post now

Article

Is the greenwashing fog about to clear?

30.09.2022, Finance and tax policy

In late May, public prosecutors in Frankfurt searched the offices of Deutsche Bank and its asset management subsidiary DWS. The reason was presumed greenwashing practices. Time to ensure greater clarity in also Switzerland.

Wind turbines near the decommissioned nuclear power plant Grohnde, Lower Saxony. – The European Union wants to label investments in nuclear energy as "green", environmental organisations criticise this sharply.

© Foto: KEYSTONE / DPA / Julian Stratenschulte

Greenwashing accusations against DWS have been rife for months now. The specific accusation is that asset managers have been exaggerating the sustainability of DWS products as regards environmental protection and climate change. According to the Public Prosecutor's Office, sufficient evidence has been found to show that ESG criteria (environment, social, governance) are being observed only for a fraction of investments.

Last year, the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the German Federal Financial Oversight Authority (BaFin) launched separate investigations into allegations by a whistleblower that DWS was selling its funds as more environment-friendly than they in fact were. The greenwashing allegations that came to light in August sent DWS shares plunging by more than 20 per cent, and precipitated the resignation of CEO Asoka Wöhrmann.

And what is the situation in Switzerland?

This case was viewed as a shot across the bow of the entire finance industry, which is under regular suspicion of engaging in greenwashing practices. Here in Switzerland too, the Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority (FINMA) is now taking an interest in communication relating to financial products: it now conducts more inspections in an effort to combat misleading advertising with "green" promises.

Recent years have witnessed a substantial rise in demand from clients and investors for sustainable financial products and services – coupled with the danger that clients and investors could be deceived about the supposed sustainable properties of financial products and services (financial products labelled "sustainable", "green" or "ESG").[1] Greenwashing is the term applied when customers of financial institutions are knowingly or unknowingly deceived or given misleading information about the sustainable properties of financial products.

FINMA's tasks include protecting financial market clients and investors from improper business practices, especially deception. FINMA investigations have now produced clear evidence of greenwashing practices in the sale of financial products and services, and determined that providers often make "vague to misleading promises" about their products.

To counter the risk, transparency around sustainability must be enhanced as a matter of urgency, by introducing standardised requirements and indicators, classifications (taxonomy) and methods for gauging the positive and negative impacts of investments on the climate and on sustainable development. Under the Paris Climate Agreement, Switzerland assumed commitments that also apply to its financial centre.

No specific legislative basis

There are currently no specific transparency-related provisions governing products and services that are described as "sustainable". Only general rules apply, including the prohibition of deceptive practices in connection with collective investment schemes (investment funds). Investors should be in a position to make well-founded investment decisions, including in the cases of products declared as "sustainable". FINMA published guidelines in November 2021, laying out the information that Swiss funds must provide in the documentation when they are declared as sustainable. When applying for authorisation, those funds are required to supply additional information as to the sustainability goals being pursued, their implementation and the expected impacts. This enables FINMA to better assess whether there is deception and to take appropriate action.[2]

Despite this, FINMA has only limited leeway for effectively preventing and combatting greenwashing. There are no specific sustainability-related transparency obligations and effective control parameters on which basis to take measures. Only additional regulatory measures would provide FINMA with the tools it needs to be able to combat greenwashing more comprehensively and effectively.

Let us not forget the Federal Council’s announcement, in late 2021, of its intention to make Switzerland a market leader in sustainable financing. At the time it urged financial market players to strive for enhanced transparency by introducing comparable and meaningful climate compatibility indicators that would enable investors to classify and select investments according to their impacts on the climate. In that context, the Council unveiled “Swiss Climate Scores" in late June, and recommended their use by financial market players purely on a voluntary basis.

By the end of 2022, the Swiss Federal Departments of Finance and the Environment (FDF and DETEC) are expected to produce a report on the implementation of these recommendations by the financial sector and – in conjunction with the FINMA – to table concrete suggestions on changes that are needed to financial market legislation in order to avoid greenwashing.

Considering the significance of the Swiss financial centre, the Federal Council would be well advised to bring forward an ambitious and future-ready regulatory framework which, at the very least, incorporates the relevant EU regulations. This could curb greenwashing practices so that financial flows from Switzerland could be credibly and measurably redirected – for the benefit of the climate and sustainable development.

[1]In 2020, "sustainable" funds grew by 50 per cent and their cumulative volume surpassed that of "unsustainable" funds for the first time.

[2]Among the practices covered by the term greenwashing, FINMA mentions collective investment schemes that purport to be sustainable when in reality no sustainable investment policy or strategy is being pursued, or collective investment schemes that use terms like "impact" or "carbon-neutral" to suggest sustainability, in the absence of any means of measuring or verifying the resulting impacts or savings.

Article

The UN makes history

22.11.2023, Finance and tax policy

In New York, a vast majority of UN Member States has voted in favour of a UN framework convention on tax. That is a major success for the Global South and, for the world community, an opportunity to create truly globally applicable rules for the first time in the history of international tax policy.

© Dominik Gross

In New York today, 125 UN Member States backed the creation of a UN framework convention on taxation. The countries of the Global South voted almost unanimously in favour. Surprisingly, some OECD members abstained. These were Norway, Iceland, Turkey, Mexico, Costa Rica and candidate country Peru. Colombia and Chile actually supported the resolution. Switzerland, along with all other OECD countries, including the US, the UK and the EU, rejected it en bloc. The decision is historic: such a convention had already been mooted in 2015 at the Third Conference on Financing for Development in the Ethiopian capital Addis Ababa, but was ultimately not included in the Addis Ababa Action Agenda (AAAA) adopted at that time. For the first time in the century-long history of multilateral tax policy, the UN is witnessing the creation of a truly global forum with legally binding decision-making, where all countries can negotiate and vote as equals on the future rules of international tax policy. The principles and elements of the convention will be defined over the coming year: for example, tax transparency and the taxation of multinationals or offshore assets.

There are a number of reasons why what was utopian for the global tax justice movement ten years ago has now become possible. The first and most important is the failure of the OECD – the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Over the past 15 years, it has failed to introduce tax reforms that would have raised substantially more tax revenue for the countries of the Global South. To be sure, the OECD has recently tried to shed its image as an exclusive club for the richest countries (there are only 38 members). It has also sought to dispel the widespread impression that it is only concerned with securing (tax) privileges for its members. As a result, non-members have been able to take part in negotiations since 2016. However, the introduction of a minimum tax for global companies is of little benefit to the countries of the South that make up the G77 at the United Nations (a group that now has 134 members). Countries such as the US, Ireland and Switzerland, for example, have turned their recent corporate tax reform into a rewards programme for low-tax countries.

This is why the G77 countries have now turned to the UN. The OECD, for its part, may now see its relevance in international tax policy issues substantially diminished: leading countries such as the US, Canada, China and other Asian countries have in recent months raised doubts about their national implementation of the latest OECD reform. In Switzerland, the Swiss business federation Economiesuisse and other representatives of the business community have recently spoken out in parliament along these lines, calling for the introduction of the minimum tax in Switzerland to be postponed. All this is grist to the UN tax mill. If the countries of the North block progress there, the result could be a global corporate tax system in the form of a one-sided patchwork that serves neither the interests of companies nor those of countries. This is exactly what the OECD was trying to prevent during its last reform period, but it is failing precisely when it comes to implementation by individual countries and their willingness to push ahead with OECD reforms. The first pillar of the reform, the reallocation of some taxing rights over companies from home jurisdictions to market jurisdictions, is falling by the wayside in Paris.

The USA, EU and Switzerland must shift positions

In recent days, prominent economists and former politicians such as Joseph Stiglitz, Jayati Gosh, Thomas Piketty or Thabo Mbeki, have come out in favour of a UN tax convention. The Global Alliance for Tax Justice, of which Alliance Sud is a member, has been campaigning for this for decades. We urge Switzerland to play a constructive role in the forthcoming negotiations on the implementation of the convention. So far it has been most notable for its disregard for the project. In the context of its current Security Council mandate, Switzerland – still seen abroad (and rightly so) as an old-fashioned tax haven – now has a unique opportunity to act as a bridge-builder at the UN and as a stabilising force between the blocs in the field of economic policy. Such a stance would be consistent with its campaign slogan for the Security Council: "A Plus for Peace". Finally, a global tax policy that raises revenue for all countries is also a security policy, because sufficient tax revenue is the basis for a strong community with good education, public infrastructure and an efficient social and health sector. These are key components of poverty reduction, as for the promotion of democracy, migration management, and the prevention of terrorism. Last but not least, greater global tax fairness is essential in order to finance holistic and sustainable development around the world, which the international community hopes to achieve by 2030 through the UN's Sustainable Development Goals. The past 10 years have shown that in this regard, the OECD is incapable of delivering. Like all other "blockers" from the North, Switzerland too should change its position and contribute constructively to the drafting of the convention.

Greater economic policy cooperation in a divided world

The current developments in tax policy at the UN also have a geopolitical component: the first UN resolution on strengthening tax policy was unanimously adopted by the General Assembly a year ago. Given the geopolitical situation at the time, the Northern countries did not dare to further alienate the G77 countries after their anger over the global response to the pandemic (vaccination inequality), the largely unmitigated consequences of the war in Ukraine for the Global South (food crisis) and the climate and debt policies of the North (little understanding of the situation in the South). They were anxious not to drive the South further into the arms of Russia and China. Abandoning the willingness shown a year ago to engage in fiscal and hence economic cooperation would be highly risky for the West. A constructive approach, on the other hand, would create an opportunity to restore universalist perspectives, at least in tax matters, in a world where very strong centrifugal forces are currently at work.

Share post now

Article

Eurocentric elation

07.12.2021, Finance and tax policy

In October, the OECD and G20 approved the new international minimum tax for multinational corporations. Hailed in Europe and North America as a historic success, the decision is being sharply criticised in Africa, Asia and Latin America.

Pecunia non olet ("Money doesn't stink"): At the G20 summit in Rome at the end of October leaders met in front of the Fontana di Trevi to throw a euro coin minted especially for them into the fountain.

© Roberto Monaldo/Keystone/APA/laPresse

In mid-October, the over 120 member states of the OECD “Inclusive Framework on BEPS”, and ultimately also the G20 countries, decided to introduce a new international minimum tax. Phrases like “Historic agreement!”, “Global tax revolution!”, “Paradigm shift!” rang out in the European or North American public arenas. The enthusiasm was less on other continents: tax justice NGOs from Africa and Asia decried the OECD agreement as a “Tax deal of the rich” and the G24 countries – an alliance of African and Latin American governments from developing and transition countries – were critical of the loss of national tax autonomy that would come with the new rules. It will mean that countries that retain their unilateral digital taxes or introduce new ones would face the pressure of OECD sanctions. In reaction to what the South deems an inadequate deal, the content of which was largely shaped by a compromise between the USA, Germany, France and the leading corporate tax havens such as Ireland, Holland, Luxembourg and Switzerland, the G77 countries (the group of developing countries at the UN) tabled a resolution calling for an intergovernmental body under the UN umbrella to take over political leadership in international tax policy matters from the OECD and which would embody much better representation of former colonial States in the Global South.

OECD minimum tax ineffective from a development policy standpoint

From the standpoint of the Global South, the reform is inadequate for two main reasons. First, the entire commodity trading industry and financial sector have been left out of the tax base redistribution. This means that countries in the Global South, which are heavily dependent on the exploitation of raw commodities, will obtain no additional rights to tax the profits of the commodities industry. Moreover, Pillar One (redistribution of corporate profits from countries of domicile to market countries) applies only to corporations with an annual turnover of 20 billion dollars and profitability of over 10 per cent. Globally, this affects only about 100 corporations – in Switzerland, presumably only such giants as Novartis, Roche, Nestlé and Schindler. This redistribution will benefit mainly rich countries with huge domestic markets like the USA or Germany. Second, the minimum tax rate of 15 per cent foreseen under Pillar Two is set far too low and can only be applied by countries where the head office of the particular corporation is domiciled. And even so, only when these corporations report an annual turnover of more than 750 million. For the Global South, what it sees as the failed OECD reform spells disaster: developing countries are suffering badly from the corporate profit shifting that is possible under the current tax system. According to a calculation done by the economists Petr Janský und Miroslav Palanský (2019), those countries are losing tax revenue of about 30 billion dollars annually through profit shifting to corporate headquarters in the North. But better domestic revenue mobilisation – as defined also by Switzerland among the goals of its technical development cooperation — can only succeed if the outflows of taxable revenue to low-tax jurisdictions are halted. For 40 years now, multinational corporations have been constantly expanding these tax avoidance practices, kindly assisted by their countries of domicile in the Global North. The reform pillars now approved by the OECD and G20 countries will change nothing about this.

Nestlé, Glencore, Socfin: new tax avoidance cases in Switzerland

The insufficiency of the new OECD rules has been borne out by recently revealed tax avoidance cases involving corporations like Socfin (palm oil and rubber trade), Glencore (oil, copper, coal and other commodities) and Nestlé (food) in each of which low-tax jurisdiction Switzerland plays a key role. The study entitled “Cultivating Fiscal Inequality”, recently published by Bread for All, the German Tax Justice Network and Alliance Sud, shows that Socfin declares the bulk of its profits for taxation in Freiburg in Switzerland. Most of the work of the corporation, however, takes place on plantations in Sierra Leone, Liberia or Cambodia, which is where, by extension, value is created. The example of Nestlé in Morocco shows just how indispensable it is to have a strong national fiscal administration: owing to unfair transfer pricing calculations, the tradition-rich Swiss corporation could be liable for record-breaking supplementary tax payments of 110 million dollars. Had the tax authorities been unable to look closely at the corporation’s dealings, this would not have been possible. Yet this is precisely the type of resources that many developing countries lack. Another report published in late October by CICTAR (Centre for International Corporate Tax Accountability and Research), a research NGO, shows profit shifting by the Glencore commodity company from Australia to the Canton of Zug, linked to its coal business. Although there is no direct development policy context in this instance, the study shows how Glencore’s canton of domicile derives direct tax benefit from one of the most climate-damaging businesses in existence. Through its low-tax jurisdictions for multinational concerns, Switzerland is hampering the equitable environmental transformation of global society not only in economic terms but also directly through policy.

Switzerland as advocate for corporations at the OECD

In a coalition with other low-tax jurisdictions like Ireland, Luxembourg, Holland or Hungary, Switzerland always favours the most lax possible reforms in fiscal policy negotiations at the OECD. The country did so again during the most recent reform process. This is revealed in a letter, now made public, sent by SVP Finance Minister Ueli Maurer to the new OECD Secretary-General Mathias Cormann in August. In it, Maurer demands deductions from the minimum tax for members of conglomerates that undertake Research & Development (which favours the interests of the Basel pharmaceutical giants) and suggests an additional rule whereby multinational corporations could deduct from their profit taxes any CO2 taxes they have paid. A preposterous suggestion, considering that through their tax avoidance practices, multinational corporations are undermining global efforts to counteract the climate crisis and would at the same time be compensated for their incentive taxes, which are targeted precisely at climate-damaging practices so as to encourage companies to invest in green technologies.

Cormann’s reply reveals the crazy nature of Maurer’s suggestion. “Carbon taxes are taxes on inputs [what is taxed is the CO2 emitted during production, DG’s note] not income [i.e. corporate profits, DG’s note] and therefore do not fit with the conceptual or design framework of the two pillars”. It is all the more remarkable that Maurer was obviously more successful with his first demand, that of introducing new deductions from the minimum tax for pharmaceutical corporations. In the wake of the OECD agreement, the Federal Department of Finance proudly announced the following in the Handelszeitung as a Swiss success in Paris: by being able to treat personnel and infrastructure costs as deductions, corporations reduce their taxable income by 10 or 8 per cent over the first five years following the introduction of the minimum tax (and thereafter by 5 per cent each time). These deductions will be at the expense of the Swiss tax administration. Not only is the responsible State Secretariat for International Finance (SIF) in the Federal Department of Finance (FDF) not representing the interests of a global community at the OECD, it is not even representing the national interests of Switzerland as a whole, but quite simply and exclusively those of the multinational corporations domiciled here. What this shows is that anyone in Switzerland who stands up for a more just global tax policy and a paradigm shift in the local low-tax jurisdiction cannot rely either on the OECD or on the Federal Council. This is an opportunity for progressive political forces and civil society.

How Switzerland could enhance the OECD reform

The encouraging aspect of this is that the minimum tax calculated by the OECD could be improved with relatively few technical changes such that it would also benefit even poor countries where production takes place. The vehicle for this would be the Minimum Effective Tax Rate (METR) for multinationals – developed by civil society players in international cooperation with economists and tax lawyers. Basically, it relies on the same technical concepts as the minimum tax of the OECD. But first it remodels the OECD’s minimum tax in such a way that the METR can be implemented by individual countries or jointly by groups of countries. Unlike the implementation of the OECD’s Pillar Two, this would not require a new multilateral agreement or changes to existing bilateral double-taxation agreements – yet another flaw in the OECD concept. Second, the METR is equally applicable to countries of domicile of corporations, countries that are sales markets and those where production takes place. This entails first calculating a corporation's total undertaxed profits. Undertaxed profits are defined, as in the OECD proposal, in terms of a minimum tax rate. Whatever falls below this rate is deemed undertaxed. Whereas the OECD’s Pillar Two prescribes a minimum tax rate of 15 per cent, the METR would presuppose a rate of 25 per cent, being guided by the current global average, which is just below that.

In a second step, these undertaxed profits would thus be allocated to those countries in which a corporation effectively creates its value. This is based on formulary apportionment, which considers (a) the capital base (physical assets), (b) payroll, and (c) sales of a corporation in a particular country.

In a third step, individual countries could autonomously tax the profits apportioned to them in accordance with their national tax legislation. This would ensure, at least in part, that a multinational corporation’s profits are in fact also taxed in the place where a certain profit-generating value is produced (in the countries of production) or sold (the market countries). The question arises however, as to whether countries that implement the new OECD rules can simultaneously introduce a minimum tax rate higher than the 15 per cent OECD rate. This would have to be a condition, if the METR is also to benefit developing countries, most of which currently have profit tax rates above 25 per cent. But it is left up to the free will of member countries of the OECD Inclusive Framework to decide whether they wish to introduce the OECD minimum tax rate.

Assuming that Switzerland were politically prepared to rethink its basic business model for dealing with multinational corporations, the country would be predestined for the introduction of the METR. As a leading host country to multinational corporations, it possesses the requisite information about their business practices to be able, at the fiscal policy level, to press ahead with implementing the METR. Besides, the country would be well-placed to find partner countries for this system, as Switzerland’s corporate taxation considerably influences the fiscal situation of a great many countries that are linked to this country through the respective multinational corporations. Were Switzerland to seek these partners, for example among the countries in the Global South where its corporations exploit commodities, or among emerging countries that serve as market outlets for Swiss consumer goods producers of the likes of Nestlé or Procter & Gamble, introducing the METR would considerably enhance the efficaciousness of Switzerland’s development policy.

Share post now

Press release

On the side of warmongers and crisis profiteers

17.05.2022, Finance and tax policy

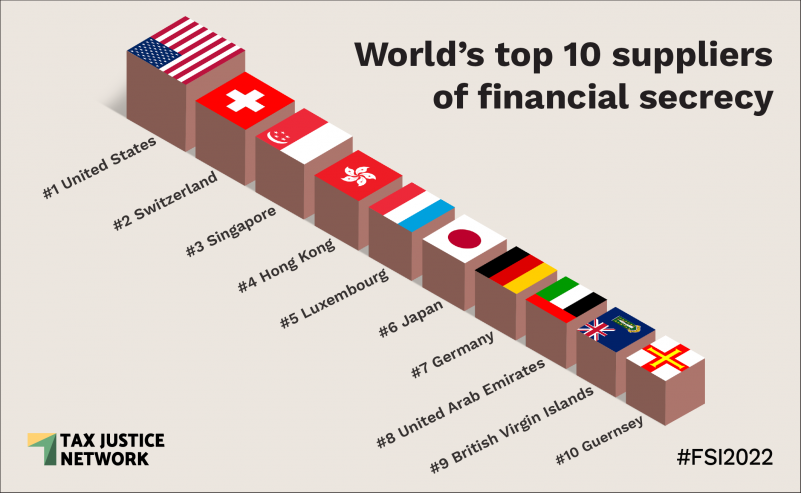

After the USA, Switzerland is the world’s most opaque financial centre. This is clear from the new Financial Secrecy Index of the Tax Justice Network (TJN).

© Tax Justice Network

After the USA, Switzerland is the world’s most opaque financial centre. This is clear from the new Financial Secrecy Index of the Tax Justice Network (TJN). Our country is marking time in the fight against international tax evasion, money laundering and corruption – this is currently proving to be an obstacle in the search for sanctioned funds belonging to Russian oligarchs. Greater transparency is urgently needed.

According to the calculations published today by the TJN, Switzerland is home to one of the financial centres most attractive to tax evaders, money launderers, financiers of terrorism, or corrupt politicians. For not only do Swiss banks manage more foreign assets than anywhere else in the world – currently more than 3,600 billion francs according to the Swiss Bankers Association – but despite all the reforms of the past 10 years, the Swiss financial centre remains one of the world’s least transparent.

As regards the Russian war of aggression in Ukraine, this is problematic for two reasons, says Dominik Gross, Financial Policy Expert at Alliance Sud, Switzerland’s centre of excellence for international cooperation and development policy: “First, Switzerland lacks the laws under which the authorities could undertake an active search for much of the sanctioned assets belonging to Russian oligarchs. TJN studies make this clear.” According to the State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (SECO), just 6.3 billion francs in Russian assets are currently frozen in Switzerland, the banks having again released more than one billion since April. And this even though, according to the Bankers Association, there are some 150-200 billion in Russian assets in Switzerland.

In addition, because Switzerland still undertakes no automatic exchange of information on financial accounts (AEOI) with many developing countries, tax evaders from non-AEOI countries still have virtually nothing to fear with Swiss banks. Gross continues: “They hide money here from the tax authorities in their home countries, where it is urgently needed for coping with the food crisis triggered by the war in Ukraine.”

Parliament must act

Despite the pressing need for action, the Federal Council remains inactive. The National Council and Council of States could soon rectify that, however:

- A cross-party motion in the National Council calls on the Federal Council to bring forward a draft law to ensure greater transparency, so that the true owners of shell companies and beneficiaries of offshore entities are at least known to the authorities.

- Other initiatives by National Councillors request the Federal Council to outline the way it intends to identify and confiscate sanctioned assets, and call for a Swiss Task Force to be created, or for Switzerland to join the international task force that is actively seeking Russian assets.

- A postulate by the Foreign Affairs Committee of the National Council requests the Federal Council to prepare a report setting out its plans for making financial flows in and through Switzerland more transparent.

Further information:

Dominik Gross, Financial Policy Expert at Alliance Sud: +41 78 838 40 79

Share post now

Article

New tricks with the tonnage tax

03.10.2022, Finance and tax policy

What the Federal Council and corporate lobbies are portraying as innocuous support for the shipping industry could prove the biggest tax loophole for Swiss commodities groups and circumvent the new OECD minimum tax.

The commodities sector benefits from the crisis – and soon from lower taxes in Switzerland?

© Stefanie Probst

In the view of advocates of Switzerland’s low-tax policy, commodity trading companies in Switzerland have come up somewhat short in recent years. Under the most recent corporate tax reform in 2019 (tax reform and AHV financing, TRAF), the Confederation scrapped the old tax privileges for holding and mixed companies (whereby Swiss corporate profits generated abroad were subject to zero taxes), from which the commodity groups had benefited substantially in the past. While the conservative majority in the federal parliament created new and special deductions for pharmaceutical and consumer goods companies custom-tailored to these industries to compensate for the old privileges, the commodities industry was left empty-handed. This is now to be corrected through the “tonnage tax”. Ostensibly, it is merely a tax break for Swiss shipowners, but as noted by the Federal Council in its dispatch on the tonnage tax, there are very close ties between them and commodities traders. Besides, it is already the case today that, if a commodities trader allows its intra-group shipping company to charge inflated freight rates – which cannot be detected in practice – profits of other companies in the same group can be reduced and taxes avoided in that way.

Rebirth of a concept already written off

During the most recent company tax reform, the Federal Council had removed the tax from the options, primarily out of concerns over constitutionality. With the tonnage tax, vessels are no longer to be taxed on the basis of the profits they earn for their operators, but based on net tonnage. The “net profit” thus obtained from navigation is then imputed to a firm’s profits from its other fields of activity. As this would mean that the taxation of certain companies would in principle diverge from the regular profit taxation method, the Federal Council at the time questioned its compatibility with the constitutional principle of taxation based on economic performance, and commissioned two legal opinions on the matter. In 2015, they both reached opposite conclusions. Robert Danon from Lausanne reached a negative conclusion, while Xavier Orberson from Geneva confirmed the constitutionality of the approach. Both law professors, by the way, hold lucrative mandates with business law firms that undertake tax optimisation for corporations. The key difference between the two opinions is that, unlike Danon, Orberson sees an existential threat to Switzerland’s maritime shipping industry and therefore considers the introduction of this flat rate taxation to be warranted under article 103 of the Swiss Federal Constitution as a structural policy measure. Considering the enormous importance of shipping to the world economy and how closely it is intermeshed with commodities traders – which are among Switzerland’s biggest and most profitable companies – that is a rather odd statement. At the time, the issue was too much of a hot potato for the Federal Council, whereas today, that body has obviously overcome its doubts even though the constitutional backdrop remains unchanged. In addition to misgivings about its constitutionality, the proposed law raises two other key problems:

- Taxation level: This would diminish significantly across all Swiss cantons compared with the regular profit tax rates. As the legal scholars Mark Pieth and Katrin Betz show in their new book on Switzerland’s shipping industry, the introduction of the tonnage tax means an average effective profit tax rate of roughly 7 per cent. That is substantially below the 11 per cent accorded to Glencore and other companies by Zug the commodity hub – and Switzerland’s fiscally most advantageous canton. In addition, the more environment-friendly the propulsion systems of vessels, the greater the tax relief the Federal Council is prepared to grant. If the maximum assessment of 20 per cent is accorded, average taxation can fall to as low as 5.6 percentage points. What is especially scandalous about this is that the Federal Council wishes to exclude profits subject to the tonnage tax from the new OECD minimum tax, which is designed to ensure that multinational corporations in Switzerland are taxed at a rate of at least 15 per cent. The introduction of a tonnage tax therefore circumvents international efforts to stop the “race to the bottom” in corporate taxes at what is already a very low level.

- Lacking environmental and labour standards on ships: The Federal Council and, up to now, also the Economic Affairs Committee of the National Council (the latter body is not expected to complete its discussion of the matter until 15 November) have been reluctant to tie the new tax privilege to what is known as a flag State requirement. That requirement would mean that shipping companies could benefit from the tonnage tax only in the case of ships sailing under the Swiss flag or the flag of a European Economic Area member State (EU countries plus Iceland, Norway and Lichtenstein). That would be an incentive to shipowners not to transfer their vessels to so-called flags-of-convenience countries, which constitute quasi-legal vacuums in the shipping industry, where they hardly need to comply with any government requirements in order to pursue their business. In the case of ships sailing under the Swiss flag, operators could be held to better environmental and labour standards. Pieth and Betz are of the view that “however problematic the tonnage tax may be,[…] it would still have indirect advantages: anyone having to register at least 60 per cent of their fleet under flags from the European Economic Area or the Swiss flag would potentially be subject to EU rules against unregulated scrapping in south Asia. However, the debate around corporate social responsibility in Switzerland also shows that the desire for higher standards in terms of the economy and human rights is rather modest within the ranks of the conservative majority in Federal Berne.

Constitutionally questionable, circumventing the OECD minimum tax and devoid of labour and environmental standards – introducing the version of the tonnage tax that is currently under discussion in the National Council’s Economic Affairs Committee would do credit to Switzerland’s dubious reputation as a tax haven for corporations. Besides, the companies that would stand to profit most are the very ones that garnered record profits on the back of the war and the energy crisis. Based in Baar in Zug, Glencore – the world’s second biggest oil trader (after Vitol, also headquartered in Switzerland) – generated a record profit of US$12 billion for the first half of 2022. Rather than provide additional scope for tax dumping by these war profiteers, the National Council and Council of States should bring in an excess profits tax to tap into these war profits and use the proceeds to help fight the multiple global crises.

Share post now

Article

Haircuts for corporations

23.03.2023, Finance and tax policy

In view of the polycrisis, the UN is calling for a "haircut", a debt cut of 30%. It is high time that Swiss commodity traders also accept this.

© Silke Kaiser / pixelio.de

A train hurtles towards the buffer stop without braking, there are many people standing around the crucial switch, but no one moves it in order to avert the catastrophic crash. This image is a fairly accurate reflection of the current approach to the sovereign debt of the poorest countries.

According to the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), at least 54 countries in the Global South are suffering from serious debt problems. Most of them are in sub-Saharan Africa (24 countries), followed by Latin America and the Caribbean (10 countries). They are home to more than 50 per cent of the people living in extreme poverty. Twenty-eight of these countries are among the 50 States most vulnerable to climate change in the world. The UNDP is calling for a "haircut" – a 30 per cent debt reduction.

Yet there is no lack of warning voices. The chief economics commentator of the Financial Times recently wrote that we were facing the threat of a "lost decade". It was a reference to the Latin American debt crisis of the 1980s and its dramatic consequences for those it affected. Although now, as then, interest rate hikes in the North are causing capital outflows from the South, there is one major difference: instead of banks, which were lending directly to countries back then, it is now investment funds like Blackrock that are investing money from pension funds and private investors in government bonds issued by countries in the Global South.

And there is also a major new player in the game: China. The world power holds the same amount of debt as all other lending countries combined (about 10%). However, this is less than a quarter of the debt owed to private creditors (the rest is held by multilateral institutions like the World Bank).

The upshot is that in the negotiations, all the parties are blaming each other. The West deplores the lack of cooperation from China, which in turn points to the fact that private lenders are unwilling to cut their debts, and that the multilateral agencies, too, with their privileged status, are also not participating.

And what is Switzerland’s role? We do not know. There is no transparency about the role of Swiss investors in the Global South. The only thing that is clear is that – besides China – there is yet another new protagonist on the scene: Swiss commodity traders. Here, too, the veil is rarely lifted. For example, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has revealed that Chad’s debt to Glencore surpasses a billion dollars – more than a third of the country's total debt. The commodities multinational, which is based in the Swiss low-tax canton of Zug and has just tripled its annual earnings on the back of war profiteering, steadfastly refuses to agree to a debt reduction. It is therefore incumbent on Switzerland to create transparency and ensure that its multinationals go to the hairdresser and agree to a "haircut".

Share post now

Press release

Tax optimisation at the expense of the poorest

20.10.2021, Finance and tax policy

The agribusiness group Socfin shifts profits from commodity production to the low-tax canton of Fribourg. This tax avoidance goes hand in hand with profit maximisation at the expense of the population in the affected regions in Africa and Asia.

The rubber plantation of the Salala Rubber Corporation (SRC) in Liberia covers about 4500 hectares of land.

© Brot für alle

A report by Bread for all, Alliance Sud and the German Network for Tax Justice on the tax strategy of agribusiness corporation Socfin reveals how multinational companies can shift profits from countries where they produce commodities in Africa and Asia to tax havens like Switzerland. These strategies are highly unjust, even if they may comply with OECD rules. Tax avoidance of this nature is tantamount to extracting profits at the expense of people in the countries of production.

Download the Report: Cultivating Fiscal Inequality: The Socfin Report

Share post now

Article

Debt brake: cost-cutting with a passion

09.03.2023, Finance and tax policy

During the pandemic, the debt brake was declared a national shrine. In financial policy terms, it was deemed a condition sine qua non for Switzerland's successful handling of the crisis. But is that really so? A ride through austerity hell.

Bundesrätin Karin Keller-Sutter, fotografiert im Bundeshaus, Bern, Schweiz.

© Raffael Waldner/13Photo

Federal finances are in a bad way," said the new Swiss Finance Minister Karin Keller-Sutter a few weeks ago at a press conference, as she presented the federal government's accounts for 2022 and assessed fiscal policy for the years ahead. Last year recorded a deficit of 4.3 billion francs, sizeable deficits are also in prospect for the next few years, and the Federal Council wants to cut costs. But if we plough through the Confederation's finances for the past 20 years and through the rules of the debt brake, what we find is that it is the latter that is mainly in difficulty.

What is the debt brake?

The debt brake was introduced in 2003. Under the Federal Budget Act, its purpose is to preserve a balance between federal receipts and expenditure over an extended period of time and thereby counter a steadily growing federal debt. The Federal Finance Administration (FFA) writes: "At the core of the debt brake is a simple rule: expenditure may not exceed receipts over an economic cycle". An economic cycle is generally construed as an extended period during which an economy goes through several phases: upswing, boom, downturn, recession, upswing. One may well think that the balance of receipts and expenditure must therefore be adjusted throughout such an economic cycle. That, at any rate, is what the above FFA statement seems to imply. It would mean that in surplus years, the Confederation would pay into a piggy bank, and in deficit years, it would draw on those savings. The piggy bank's account balance would thus have to be zero throughout the economic cycle. But the debt brake is simply not a piggy bank. The expenditure rule and the specific provisions on the compensation account prevent this. The cost-cutting devil is in the detail.

The expenditure rule

The expenditure rule requires the federal government to generate budget surpluses in years of strong economic growth, when corporate profits are high, wages and consumption rise, and the State therefore garners more tax revenue. The federal government is permitted to run deficits during downturns. Yet, under the expenditure rule, it is not enough for surpluses (positive sum of receipts minus expenditure) and deficits (negative sum of receipts minus expenditure) to balance each other out over an entire economic cycle. In good years, the expenditure rule mandates that a surplus is generated. This prompts the federal government to make savings even in good years, and drastically limits its financial leeway. If you now think of a squirrel, which does not eat all the acorns it gathers in the summer (boom years), but stores some away for the winter when food is scarce (years of downturn), you have understood the matter so far. The only thing is that the surpluses from good years may not go into the pantry for consumption in bad years, but must serve to reduce debt. This means, in a manner of speaking, that the "federal squirrel" must give the acorns it saves to the "wild boars" (the Confederation's creditors). It therefore diets in good summers, and must still go hungry in harsh winters – even though that may not be at all helpful, as we are about to see.

The compensation account

The compensation account is not really an account. It is the federal government's milk maid calculation (Milchbüchlein), but it is not a wallet. No money can be deposited into it. The Federal Finance Administration sees it as providing “control statistics for the extraordinary budget”. Budget surpluses and deficits are recorded in the compensation account. If a year's accounts show actual expenditure to be below the expenditure anticipated in the budgeting process, the positive difference is "booked" to the compensation account. The milk maid calculation therefore shows the surplus receipts accruing to the Confederation and used to reduce debt. If expenditure is higher than expected, the milk maid calculation accordingly reflects this; if it is lower than expected, this is also noted. If the balance of the amounts noted is negative, that shortfall must be offset over the ensuing years (no exact timeframe is set). What this means is that the federal government must generate surpluses in the years that follow (through additional revenue, or spending cuts), with which the compensation account can be restored to zero. Debt reduction is then also suspended until the compensation account balance is back in positive territory.

However, the compensation account has never been in the red in the 20-year history of the debt brake. Luck has also played a part. Between 2003 and 2019, the Swiss economy experienced only good-to-very-good years, except for a brief recession during the 2008/2009 financial crisis. The year 2019 therefore closed with the compensation account balance showing a positive 27.5 billion francs. But there's the rub – all of that money had already gone towards debt reduction, and the piggy bank remained empty. On the back of the coronavirus pandemic, the compensation account balance had contracted to 21.9 billion by the end of 2022. But this reduction has no implications for the federal budget, as the balance is still very high. In the past 20 years, the Confederation's debt in francs and centimes diminished from its peak of 128 billion in 2005 to 88 billion in 2019. On the back of the coronavirus pandemic, real debt again rose during the past three years, but is now already falling back. Because the economy also showed strong growth, the debt ratio (total debt to GDP) also dropped.

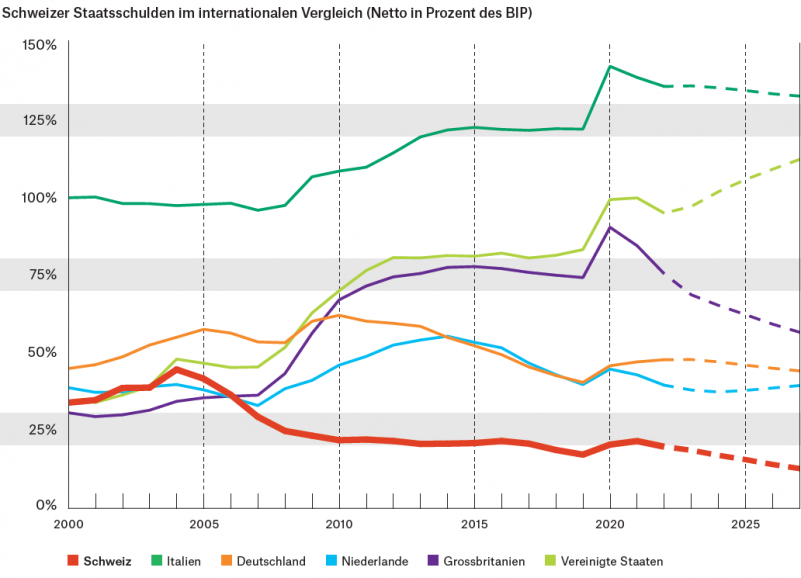

The starting point of the debt level was already very low in 2005. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), it dropped from just over 30 per cent to less than 20 per cent (the federal government's figures arrive at an even lower net debt). Today, Switzerland's debt is almost ridiculously low by comparison with its European neighbours and other majors in the financial centre.

A reduction to such a low level, including by international standards, is in fact entirely unnecessary from a financial and economic policy standpoint. The "Eidgenossen", as Swiss government bonds are called, are much too sought-after by local pension funds, investment funds and financial institutions. Investors need not factor in the slightest risk of default. The interest payable by the Confederation on its bonds is accordingly low – and will be for decades.

At the same time, however, the rules governing the debt brake significantly curtailed the federal government's financial leeway in the 2000's and 2010s: the legally prescribed debt reduction prevented the federal government from putting money aside to be spent in leaner times (that would have been a piggy bank). But that is not all – there is also the amortisation account.

Amortisation account

This account regulates the treatment of extraordinary receipts and expenditure by the Confederation. It was brought in a few years after the introduction of the debt brake by means of a legislative amendment. Extraordinary receipts and expenditure are booked to the amortisation account – for example, income from the sale of G5 licences for the mobile phone network, or very substantial extraordinary federal spending in response to the pandemic. If the amortisation account goes into the red, this must be corrected using surpluses from the ordinary budget within six years. Today this is a problem – because of the coronavirus-related costs that were charged to the amortisation account – even though things sounded quite different three years ago. At the onset of the coronavirus crisis in March 2020, the then Finance Minister Ueli Muarer successfully floated the fairy tale of the piggy bank. The date was 20 March 2020, and Switzerland had been in lockdown for a week. At a historic press conference, the Federal Councillor explained how he intended to avert the collapse of the Swiss economy, which was then in virtual paralysis: Maurer himself then asked the first question: "Yes, ladies and gentlemen, dear colleagues – erm, can the Confederation really spend 42,000 million, this 42 billion, this is perhaps the first question that should be asked." The answer was: "I can assure you that the Confederation can, thanks to the fact that our finances are very robust, thanks to the fact that we have reduced debt over recent years, thanks to the fact that we have recorded surpluses, thanks to the debt brake." In short, at the onset of the pandemic, Maurer asserted that the coronavirus bailout measures were being covered by reserves. The Finance Minister therefore personally led the public to believe that the debt brake was a piggy bank. And it worked. There was gushing praise for the debt brake up and down the land, fiscal skinflints and ideological bookkeepers felt vindicated: "Waste not, want not". The fact is that the coronavirus bailouts were made possible only because the Financial Budget Act permits the debt brake to be suspended in exceptional situations. This is covered under the "exception clause".

The exception clause

The Federal Finance Administration writes: "In extraordinary situations (e.g., natural disasters, severe recessions and other uncontrollable developments) it is possible to deviate from the [spending] rules". And this is where we now stand. The coronavirus-related debt must now be eliminated. To this end, further new spending has been approved (in part by Parliament) owing to the war in Ukraine and efforts to combat the associated inflation and the purchasing power crisis. Had the 27.5 billion in fact been put into the piggy bank (or better yet invested and hence substantially increased), it could easily have covered the coronavirus-related deficit of 32.8 billion. The higher debt ratio (which would have diminished automatically during the following years by virtue of expected GDP growth) would have had no fiscal impacts. However, the debt brake regulations do not permit this. There were initiatives along those lines in Parliament, but they never stood a chance. In the end, a parliamentary majority still decided to offset half the costs of the coronavirus bailouts against compensation account surpluses from previous years, and extended the deadline for this reduction to 2035. Such a set-off of extraordinary expenditure against the compensation account balance ought not to be possible under the debt brake rules. In this case, however, Parliament showed little concern about that, and simply wrote a coronavirus-related exception to the exception clause into the Financial Budget Act. The fact is that in this instance, an extraordinary quasi-piggy bank was born, exclusively for coronavirus-related debt.

The upshot is that what largely determines whether the debt brake generates real pressure to cut costs is what the Federal Council and Parliament may or may not choose to include in the milk maid calculation. The question of what could in fact be funded is secondary. In any case, 16 billion in coronavirus debt still remains, and must be reduced by the Confederation by 2035 using surpluses from the ordinary budget. Hence the Federal Council's wish to cut costs, mainly in the areas of education, agriculture and, not least of all, development cooperation. These are all areas on which we will rely heavily if we are to make our society more ecological, caring and secure, and if Switzerland is to contribute appropriately to overcoming the polycrisis in the Global South. Switzerland could indeed be currently addressing problems that are more pressing than keeping its national debt as low as it has done for the past 10 years. Were it to increase by 10 per cent of GDP, or about 50 billion francs, there would not be the slightest harm to the economy, the entirety of the Confederation's current fiscal problems would be solved in one go, and substantial investments could easily be made in a Switzerland that is caring, sustainable and capable of global solidarity. The money could be had, what is now lacking is "merely" the political will to take it.

© Alliance Sud

Eine Reduktion auf ein auch im internationalen Vergleich so niedriges Niveau ist finanz- und wirtschaftspolitisch eigentlich völlig unnötig. Zu begehrt sind die «Eidgenossen», wie Schweizer Staatsanleihen genannt werden, bei hiesigen Pensionskassen, Anlagefonds oder Finanzinstituten. Investor:innen müssen hier nicht die geringsten Kreditausfallrisiken miteinkalkulieren. Entsprechend tief fallen auch die Schuldzinsen aus, die der Bund für seine Anleihen bezahlen muss – und das auf Jahrzehnte hinaus.

Gleichzeitig beschnitten die Regeln der Schuldenbremse den finanziellen Handlungsspielraum des Bundes in den 2000er und 2010er Jahren aber erheblich: Der gesetzlich festgeschriebene Schuldenabbau verhinderte, dass der Bund Geld zur Seite legen konnte, um es dann in schwierigeren Zeiten wieder auszugeben (das wäre das Sparschwein gewesen). Aber damit nicht genug, es gibt nämlich auch noch das Amortisationskonto.

Das Amortisationskonto

Dieses regelt den Umgang mit ausserordentlichen Einnahmen und Ausgaben des Bundes. Es wurde einige Jahre nach Einführung der Schuldenbremse mit einer Gesetzesänderung zusätzlich geschaffen. Auf dem Amortisationskonto werden ausserordentliche Einnahmen und Ausgaben verbucht – so etwa die Einnahmen aus dem Verkauf der G5-Lizenzen für das Mobilfunknetz oder die sehr hohen ausserordentlichen Ausgaben des Bundes zur Bewältigung der Pandemie. Wenn das Amortisationskonto ins Minus fällt, muss dieses mit Überschüssen aus dem ordentlichen Haushalt innerhalb von sechs Jahre wieder behoben werden. Das ist heute – wegen der auf dem Amortisationskonto verbuchten Corona-Kosten – ein Problem, auch wenn das vor drei Jahren noch ganz anders klang. Zu Beginn der Corona-Krise im März 2020 setzte der damalige Finanzminister Ueli Maurer nämlich ein in der Folge das erfolgreiche Märchen vom Sparschwein in die Welt. Man schrieb den 20. März 2020. Seit einer Woche war die Schweiz im Lockdown.

An einer geschichtsträchtigen Medienkonferenz informierte der Bundesrat darüber, wie er die Schweizer Wirtschaft im Beinahe-Stillstand vor dem Kollaps bewahren will: Maurer stellte die erste Frage dann gleich selbst: «Ja, meine Damen und Herren, liebe Kolleginnen und Kollegen – äh, kann der Bund überhaupt 42’000 Millionen ausgeben, diese 42 Milliarden, das ist wohl die erste Frage, die zu stellen ist.» Die Antwort: «Ich kann Ihnen versichern, dass der Bund das kann, dank dem, dass wir einen sehr robusten Finanzhaushalt haben, dank dem, dass wir die Schulden in den letzten Jahren abgebaut haben, dank dem wir Überschüsse erzielt haben, dank der Schuldenbremse.» Kurz: Maurer behauptete zu Beginn der Pandemie, dass die Corona-Hilfsmassnahmen durch Rücklagen gedeckt seien. Der Finanzminister höchstpersönlich liess die Öffentlichkeit also im Glauben, dass die Schuldenbremse ein Sparschwein sei. Und es funktionierte: Landauf, landab setzte eine Lobhudelei auf die Schuldenbremse ein, finanzpolitische Geizkragen und ideologische Buchhaltermenschen sahen sich bestätigt: «Spare über die Zeit, so hast Du in der Not.» Tatsächlich wurden die Corona-Hilfsgelder nur möglich, weil das Finanzhaushaltsgesetz in Ausnahmesituationen die Aussetzung der Schuldenbremse erlaubt. Das ist in der «Ausnahmebestimmung» geregelt.

Die Ausnahmebestimmung

Die Eidgenössische Finanzverwaltung schreibt: «In aussergewöhnlichen Situationen (so etwa bei Naturkatastrophen, schweren Rezessionen und anderen nicht steuerbaren Entwicklungen) ist es möglich, von der [Ausgaben-]Regel abzuweichen. Und hier stehen wir jetzt. Die Corona-Schulden müssen wieder abgebaut werden. Dazu wurden (z. T. vom Parlament) wegen des Kriegs in der Ukraine und der Bekämpfung der damit verbundenen Inflation und der Kaufkraftkrise noch neue zusätzliche Ausgaben beschlossen. Wären die 27,5 Milliarden tatsächlich ins Sparschwein gelegt worden (oder besser noch investiert worden und damit stark gewachsen), hätte man das Corona-Minus von 32,8 Milliarden ganz einfach damit decken können. Die höhere Schuldenquote (die sich in den nächsten Jahren aufgrund des zu erwartenden BIP-Wachstums von selbst wieder reduziert hätte) hätte keine finanzpolitischen Folgen. Doch das lassen die Regeln der Schuldenbremse nicht zu. Im Parlament gab es Vorstösse in diese Richtung, doch sie blieben chancenlos. Am Ende entschied eine Mehrheit des Parlamentes immerhin, die Hälfte der Kosten für die Corona-Hilfen mit den notierten Überschüssen auf dem Ausgleichskonto aus den vergangenen Jahren zu verrechnen und verlängerte die Frist dieses Abbaus bis 2035. Eine solche Verrechnung ausserordentlicher Ausgaben mit dem Saldo des Ausgleichskontos dürfte es eigentlich gemäss Schuldenbremsen-Regeln gar nicht geben. Das kümmerte das Parlament aber in diesem Fall wenig und so hat es hier kurzerhand einfach eine coronabedingte Ausnahme von der Ausnahmeregel ins Finanzhaushaltsgesetz geschrieben. Es hat in diesem Fall also tatsächlich ein ausserordentliches Teil-Sparschwein exklusiv für Corona-Schulden geboren.

Es zeigt sich: Ob die Schuldenbremse einen realen Spardruck auslöst, hängt wesentlich davon ab, was Bundesrat und Parlament in ihrem Milchbüchlein der Schuldenbremse notieren wollen und was nicht. Die Frage, was tatsächlich finanzierbar wäre, ist nebensächlich. Von den Corona-Schulden bleiben jedenfalls immer noch 16 Milliarden, die der Bund bis 2035 mit Überschüssen aus dem ordentlichen Haushalt abbauen muss. Deshalb will der Bundesrat nun also sparen: vor allem in der Bildung, der Landwirtschaft und nicht zuletzt in der Entwicklungszusammenarbeit. Alles Bereiche, auf die wir dringend angewiesen wären, um unsere Gesellschaft ökologischer, sozialer und sicherer zu machen und einen angemessenen Beitrag der Schweiz zur Bewältigung der Vielfachkrise im Globalen Süden sicherzustellen. Es gäbe heute auch für die Schweiz in der Tat dringendere Probleme, als ihre Staatsverschuldung so tief zu halten, wie sie in den letzten zehn Jahren war. Würde sie um zehn Prozent des BIP oder ca. 50 Milliarden Franken ansteigen, ergäbe das nicht den geringsten volkswirtschaftlichen Schaden, sämtliche gegenwärtigen finanzpolitischen Probleme des Bundes wären auf einen Schlag gelöst und grosse öffentliche Investitionen in eine soziale, nachhaltige und globalsolidarische Schweiz problemlos möglich. Das Geld wäre da, jetzt fehlt «nur» noch der politische Wille, es auch zu nehmen.

Share post now

Article, Global

Mozambique's gas curse

20.06.2023, Finance and tax policy

Even at the height of the climate crisis, gas mega-projects are being mounted in Mozambique by oil majors, including TotalEnergies, in which the Swiss National Bank holds a stake. These projects are fuelling conflicts while not benefiting the people.

Downed power lines in Macomia, northern Mozambique, after Cyclone Kenneth in 2019.

© Tommy Trenchard/Panos Pictures

Following the discovery of immense natural gas reserves in 2010 off the coast of Cabo Delgado province in northern Mozambique, gas and oil multinationals have launched massive liquefied natural gas (LNG) projects. These projects figure in the OECD report on "Private finance mobilised by official development finance interventions". They include deep-sea mining (at a record depth of 2000m!), a submarine pipeline and processing plants on land, as well as an LNG export terminal. Two mega-projects (Rovuma LNG and Coral South FLNG Project) constitute a joint venture between the USA's ExxonMobil, Italy's ENI and China's government-owned CNPC. The principal shareholder and operator of the Mozambique LNG project is the France's TotalEnergies corporation, in conjunction with Mitsui (Japan) and Mozambican, Indian and Thai investors. It should be recalled that the Swiss National Bank (SNB) currently holds shares in TotalEnergies worth about 620 million USD.

Public-private funding on a gigantic scale

The total amount invested in LNG projects in Mozambique is estimated at some USD 60 billion, or almost four times Mozambique's GDP. According to the African Development Bank (ADB) – one of the project's public donors together with export credit agencies (ECA) mainly in the United States and the United Kingdom – these projects represent the largest foreign direct investment (FDI) to date and the largest project funding in Africa. They should make Mozambique the world's third largest LNG supplier, and contribute more than USD 67 billion directly to Mozambique's GDP. The projects will provide gas for export to Europe and Asia (mainly India and China), but also aims to supply LNG for the industrial development of the country and the southern African region.

Besides Mozambique, Nigeria, Egypt, Algeria as well as Senegal and Mauritania are also striving to increase their LNG exports, especially to Europe. LNG advocates deem this energy source to be indispensable to the energy transition, as it produces 50 per cent less CO2 emissions than coal-based energy. Conversely, in its report titled Net Zero by 2050 published in May 2021, the International Energy Agency (IEA) called for an immediate end to investment in fossil energy production, so that worldwide energy-related CO2 emissions can be brought to net zero by 2050, thereby limiting global warming to 1.5°C.

Islamist uprising and natural resource curse

The province of Cabo Delgado is one of the country's poorest regions. Besides being hit by cyclones and floods that have further compounded poverty and food insecurity, the region is also gripped by an uprising against the Mozambican Government, stemming from various factors, but which may also be linked to the extraction of the region's natural resources. Armed groups, some with links to terrorist organisations such as Islamic State, have launched violent attacks on local communities, forces of law and order, and on gas infrastructure. By UN estimates, more than 700,000 people have been displaced in the region since the uprising began.

The international community has provided humanitarian assistance for the people affected. In February last, the President of the Swiss Confederation, Alain Berset, together with his Mozambican counterpart, Felipe Jacinto Nyusi, visited a refugee camp and SDC projects in the province. Mozambique has been a priority country for Swiss cooperation since 1979.

The EU has in turn stepped up its financial support, among other things, for Rwandan defence forces stationed in Mozambique to ensure that the gas projects can come on stream as quickly as possible, thereby reducing EU dependence on Russian gas.

The Swiss National Bank: shareholder of TotalEnergies

According to its own information, the Swiss National Bank (SNB) currently holds shares worth almost USD 620 million in TotalEnergies capital. Besides its operations in Mozambique, TotalEnergies plans to build a 1400-km pipeline called EACOP, which will run through Tanzania and Uganda and will jeopardise the livelihoods of thousands of people and also the environment. At its recent annual meeting, the Swiss Climate Alliance, of which Alliance Sud is a member, joined other NGOs in the "SNB Coalition" in calling for all fossil assets to be divested and for SNB investment, monetary and foreign exchange policies to be aligned with the aims of the Paris Climate Agreement. Tanzanian NGO representatives have called on the SNB management to divest its stake in TotalEnergies immediately.

Share post now

global

The Alliance Sud magazine analyses and comments on Switzerland's foreign and development policies. "global" is published four times a year (in german and french) and can be subscribed to free of charge.

Publication

The upcoming referendum on corporate tax reform

22.01.2019, Finance and tax policy

On 19 May, Switzerland votes again on its corporate tax reform, which Parliament has linked to additional funding of its pension system (AHV). From a development policy point of view, the tax proposal does not represent any significant progress.

The linking by Parliament of two not related subjects - corporate taxation and AHV financing - is widely referred to as horse-trading. (in German: cow-trading)

© Pixabay

After the 50‘000 necessary signatures for a referendum against the STAF (Steuervorlage und AHV-Finanzierung) have been submitted, the Swiss voters will again decide on the pending corporate tax reform. Alliance Sud's tax policy analysis (available in German only) shows that, from a development perspective, the proposal does not represent any significant progress compared with Corporate Tax Reform III (USR III), which was rejected two years ago. Once again, the old special tax regimes that are detrimental to development are to be replaced by new ones.

The current proposal would bring Swiss corporate taxation into an internationally accepted form and finally abolish the old special tax regimes exclusively for foreign group profits taxed in Switzerland. This is very welcome from a development point of view. At the same time, however, it creates new opportunities for multinational corporations to shift profits. By shifting profits to low tax jurisdictions such as Switzerland, multinationals are depriving developing countries of an estimated 200 billion dollars of potential tax base every year.

Alliance Sud's detailed analysis of new tax dumping vehicle within the STAF shows that the envisaged new Swiss corporate tax policy is not compatible with the goals for sustainable development set out in the UN Agenda 2030 (Sustainable Development Goals SDG). As the country with the highest per capita density of headquarters of multinational corporations, Switzerland has a special responsibility in the fight against global social inequality and for adequate financing of Agenda 2030.

Due to the tax dumping of low-tax jurisdictions such as Switzerland, corporate taxation has been falling worldwide for decades. This prevents the most urgent public provision of health, education and infrastructure services to disadvantaged population groups in developing countries. Switzerland is not a freerider on the train that is pulling global corporate taxation into the abyss - it is rather one of the locomotives and will remain so with the STAF.

Despite the considerable shortcomings in the tax section of the bill, Alliance Sud refrains from a voting recommendation. The AHV part of the bill concerns a domestic policy issue that goes beyond the organization's development policy mandate. At the same time, the Alliance Sud members have different views on the question of the extent to which a developmentally just corporate tax reform is also possible beyond the current proposal. It is clear that such a reform remains necessary regardless of the result of the May vote.

Share post now