Although it is sometimes forgotten, the Paris Agreement does commit States – besides reducing their CO2 emissions and adapting to the impacts of climate change – also to directing financial flows towards low greenhouse gas and climate-resilient development. Countries are therefore expected to take appropriate steps to ensure that financial market participants use their financing and investments to help redirect capital flows towards concrete solutions for mitigating climate change and adapting to the changing climate. Simply put, “investments should be oriented towards the goals of the Paris Agreement”.

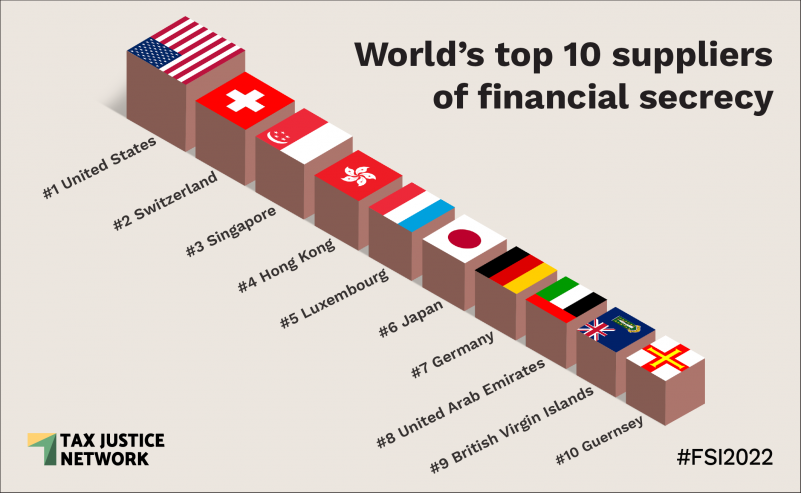

Given its global importance – 24 per cent of cross-border asset management takes place in Switzerland – the Swiss financial sector would be ideally placed to play a key role as a catalyst for driving this reorientation. But while there is general agreement on the goal, opinions diverge considerably as to the means of achieving it.

EU taxonomy: “sustainability” at last defined

In June 2020, the EU adopted the Taxonomy Regulation, which forms the backbone of its Action Plan on Financing Sustainable Growth. One of its primary aims is to identify and promote investments in “sustainable” activities that are consistent with the EU goal of climate neutrality by 2050. To this end, the Regulation creates a classification (taxonomy) of corporate economic activities, based on their potential to contribute to the EU’s six environmental objectives. At various levels, it encompasses more than 70 activities from the fields of energy, transport, forestry and construction; these account for more than 90 per cent of EU greenhouse gas emissions. Large companies are required to report their activities that are aligned with the taxonomy and to indicate the share of overall activity that they represent. This information should enable financial market participants to prioritize the funding of projects and assets that can be shown to contribute most to reductions in the direction of climate neutrality. As of 2023, large companies will also be required to disclose the degree to which their activities are aligned with the taxonomy. Financial institutions will also be subject to the same requirement starting in 2024.

For an activity to be classified as “green” under the taxonomy, it must make a vital contribution to at least one of the EU’s six environmental objectives, without significantly counteracting the other five, and must respect guarantees relating to human and labour rights. The criteria for identifying environmentally friendly activities are set by the European Commission. An initial legal instrument focused on climate has been in force since January 2022, and addresses activities that contribute to achieving the first two objectives of the taxonomy (climate change mitigation and adaptation). The criteria for the other four goals (environmental pollution, water, circular economy and biodiversity) are to be set by the end of the year. Further social criteria and governance -related aspects are also to be determined.

And in Switzerland: between competitiveness and/or sustainability

In its 2020 Report on sustainability in Switzerland’s financial sector, the Federal Council recognized the importance of a uniform system of classification for sustainable activities (taxonomy), primarily “because comparable information means transparency for clients, insured parties, investors and the public”. However, in the wake of opposition from the industry, and invoking the sacrosanct principle of subsidiarity with regard to State action, it opted to pursue a voluntary and hence a non-regulatory approach. In June 2022, it adopted the Swiss Climate Scores (SCS), which were drawn up by a working group comprising industry players, representatives of the federal administration, academia and NGOs. Their aim is to provide institutional or private investors with “reliable and comparable” information regarding the degree to which their financial investments are compatible with international climate goals. The Federal Council recommends that all Swiss financial market participants should apply the Swiss Climate Scores to financial investments and client portfolios “wherever this makes sense”.

Is the approach credible?

To be worthy of their status as “best practices” in the realm of climate transparency, the SCS are to be reviewed at regular intervals and, “if necessary”, adapted to reflect the latest insights. The Federal Department of Finance (FDF) and the Federal Department of the Environment, Transport, Energy and Communications (DETEC) have been tasked with reviewing the progress made, by the end of 2023, towards the adoption of the “Swiss Climate Scores” by Swiss financial market players – as previously noted, on a voluntary basis. It will be useful, in this context, to compare such progress with that achieved in the EU through the application of the taxonomy and other regulatory measures.

At present, the SCS raise several questions. Will they actually be implemented in the financial sector? Will mere pressure by clients on financial institutions suffice to ensure that they are implemented? Or can a sufficiently substantial climate incentive be created only by introducing further regulations to ensure that investments are consistent with the goals of the Paris Agreement to which Switzerland has signed up? To be continued in 2023.