Share post now

Analysis of the demise of USAID

Development cooperation is of systemic importance

17.02.2025, International cooperation

Much has been written in recent days about the dramatic dismantling of the American development agency USAID. It is now clear that not only was the agency destroyed in an undemocratic and unlawful manner, but that moreover, the decision is having worldwide repercussions. Despite its much-vaunted humanitarian tradition and advocacy of multilateralism through international Geneva, official Switzerland is still noticeably silent.

Protesters call on US Congress to rescue USAID. © KEYSTONE / CQ Roll Call / Newscom / Tom Williams

The US development agency USAID was founded in 1961 by John F. Kennedy. It has since grown into the world's largest development agency. With an annual budget of USD 40 billion (less than 1% of US government spending), it accounts for roughly 40% of total official development spending by all countries in the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Now, in a few short weeks, it has been completely incapacitated. Elon Musk – the world's richest man with no official mandate now at the helm of Donald Trump’s Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) – is leading the charge against USAID. In a series of hate-filled tweets, he called the development agency a "ball of worms", "a viper's nest" or a "criminal organisation", and said it was time for it to die. It is understood that shortly thereafter he ordered the sending of an email to all employees requesting them to stay at home. Then came one blow after another. Senior managers were dismissed or sent on leave. Suddenly, the USAID website, its X account and staff email accounts were no longer accessible. Besides, Musk obtained unlawful access to sensitive agency data when a group of young IT specialists (the so-called "DOGE kids") defied the instructions of the security staff and aggressively made their way into the offices of the US agency. In the same manner, the DOGE kids procured sensitive data from the departments of health, education and finance. Senator Chuck Schumer described the group as "an unelected shadow government ... conducting a hostile takeover of the federal government”.

Although the development programmes were officially paused for just 90 days, and "life-saving humanitarian programs" could apply for special waivers, the actions of Trump and Musk give every indication that the USAID is unlikely ever to be resuscitated. Consequently, a number of partner organisations have announced that they would be unable to continue the programmes despite their special waivers, as Musk's DOGE kids have paralysed the organisation's entire payment system. In addition, Trump has meanwhile issued a new government decree ordering the agency to cease granting further waivers. Cynically, only military aid to Israel and Egypt continues unchanged. In the meantime, all employees have been instructed to return home to the USA, the "USAID" letterhead has been removed from the New York office, and official communications now refer to the agency as the "former USAID". In just a few weeks, an agency that was created by the American Congress, and whose budget is approved annually by Congress, was fed "into the wood chipper" by an unelected government representative (to use Musk's own words). Although numerous lawsuits have now been filed in the USA against the actions of Trump and Musk, it is not clear whether these will have any real impact, because, on the one hand, much of the judiciary is dominated by Republicans, and on the other, statements by President Trump and his Vice-President Vance suggest that any court rulings intended to curtail Trump's executive power will be ignored.

Devastating worldwide consequences

The shutdown of USAID is catastrophic not just from the standpoint of democracy, but it is also having serious repercussions around the world. Because the USAID conducts numerous projects jointly with other organisations, the international development system as a whole is being severely undermined. In addition to some 10 000 USAID employees who lost their jobs more or less overnight, thousands of jobs have already been slashed also in partner organisations that implement projects for USAID. Estimates are that more than 50,000 jobs have already been lost and that this number will climb to over 100,000 in the months ahead. Various Swiss NGOs, too, will have to lay off several hundred local employees. Many smaller partner organisations in countries of the South have already ceased operating altogether.

It is no exaggeration to state that the shutdown of the USAID holds life-threatening implications for millions of people. One example is the realm of healthcare, where USAID plays a pioneering role: its disappearance means that millions of people will now no longer be receiving vital medicines. The African Health Agency Africa CDC anticipates that there will be two to four million deaths per year as a result.

The abrupt closure of the USAID has meant, among other things, that tonnes of food are now rotting in warehouses as hundreds of thousands of children await their school meals, or that 11.7 million girls and women have no access to contraceptives. This considerably heightens the risk of unwanted pregnancies and childbirth complications.

Independent media coverage, too, will be severely impacted in many countries. In the year 2023, for example, USAID funded training and support for 6200 journalists, assisted 707 non-governmental news broadcasters and 279 civil society organisations that work to strengthen independent media in more than 30 countries, including Iran, Afghanistan and Russia.

Growing security risks

Clearly, neither Trump nor Musk cares about the demise of many NGOs in the Global South. In this country, too, some opponents of development cooperation are already rejoicing and wishing to see the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation eliminated. But the abrupt closure of USAID also harbours serious medium-to-long-term security risks – indeed globally.

USAID, for example, is largely responsible for monitoring and containing the Ebola virus in West Africa and also for the surveillance of avian flu in 48 countries. Combined with the withdrawal of the USA from the World Health Organisation, this shutdown has lethal implications and the risk of a global pandemic is growing.

The discontinuation of vital emergency relief in war-torn and crisis regions can also quickly lead to new waves of migration. Various experts are already warning that the vacuum left by the dismantling of USAID will benefit countries like China and Russia, which will now gladly step into the breach with the usual anti-Western rhetoric.

Crisis as opportunity?

The dismantling of USAID comes as the worldwide climate crisis worsens and the attainment of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) proves ever more elusive. The OECD now estimates the funding shortfall for attaining the SDGs by 2030 at USD 6.4 trillion. In parallel, several European countries, including Switzerland, have cut development spending in recent years, and the international climate finance gap is growing steadily wider.

A rising number of countries are currently entrenching themselves behind their own national interests, and far-right propaganda seems to have regained social acceptability in many places. Besides affecting critical accomplishments in the areas of diversity, gender justice and the fight against racism, this is also strongly impacting development cooperation.

The global development system is certainly in need of reform – local players, for example, must have a greater role in designing and implementing projects. An open discussion on the future of development cooperation is to be welcomed. What has befallen USAID, however, is the exact opposite. The radical policies of Trump and Musk clearly demonstrate not just the massive worldwide repercussions of the abrupt elimination of a development agency, but also how quickly a democracy can be damaged and extreme right-wing ideology and rhetoric can take hold.

It now seems all the more important for countries like Switzerland, which are happy to brag about their democracy and their humanitarian values, to take a clear stand and strongly condemn the dismantling of USAID. Moreover, as host to an international cooperation hub in the form of international Geneva, Switzerland should now make common cause with other donor countries to financially cushion the loss of USAID and position itself over the long term as a defender of multilateralism and democracy. This is the only way that the crisis into which Trump and his acolytes seem to be plunging the entire world could yet perhaps represent an opportunity.

Tied aid

Who benefits from Swiss development funds?

29.11.2024, International cooperation

For decades, aid tied to countertrade transactions has been frowned upon in international cooperation. Donor countries seem hardly bothered by it, however. On the contrary. In Switzerland, too, tied aid is again becoming acceptable. An analysis by Laura Ebneter

No economic aid for Swiss companies yet: In March 2022, after the start of the major Russian offensive against Ukraine, Switzerland delivers humanitarian aid. © Keystone / Michael Buholzer

In an interview with Swiss Radio and Television SRF in the summer of 2024, Helene Budliger-Artieda, Director of the State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (SECO), said the following: "In our work of development cooperation, we strive primarily to place orders in the local economy. But this is about reconstruction [in Ukraine]. In this case, we have a different logic". The interview was about the Federal Council's plans for supporting Ukraine. The Federal Council has earmarked 1.5 billion francs for support to Ukraine over the next four years. Of this amount, 500 million is to benefit Swiss companies operating in Ukraine. Is this still development cooperation or is it export promotion?

This is an instance of tied aid, which is frowned upon. The term covers development funds that are made conditional on the procurement of goods and services from donor countries. This is why it is often referred to as shopping vouchers. The partner countries are left no choice: in an emergency, we also accept Migros shopping vouchers, even if this harms our own village shop, which would be much more important for locals in the medium term.

Bad deal for the Global South

All available estimates arrive at the same conclusion – if goods and services must be bought in donor countries, projects cost 15-30% more than if countries are able to choose a supplier. Yet, cooperation without countertrades enhances more than just efficiency in the use of funds and self-determination on the part of partner countries. Promoting local markets and companies also generates positive stimuli that go beyond project outcomes. If local suppliers are used, it becomes less problematic to obtain spare parts, as the supply chains are significantly shorter. Maintenance costs will otherwise be higher and can jeopardise long-term success if funds are lacking upon completion of the project.

Has history taught us nothing?

Tied aid is part of a decades-long debate on the effectiveness of development financing. In essence, it is about two closely related concerns. One is future-oriented international cooperation based on principles of effectiveness and efficiency. This means that the debate on tied aid also has a bearing on the decolonisation agenda, in that partner countries should be able to determine their own development path. The other relates to the potentially distorting effects of tying allocated funds to the export of goods and services from donor countries.

It is also about a level playing field. After all, those countries that forego the practice of tied aid – instead putting their contracts up for international tender – justifiably assert that they would be at a disadvantage if other countries failed to follow suit. Hence, Swiss suppliers, for example, have only limited access to other markets, while international suppliers have ample access to Switzerland's procurement system.

To facilitate international coordination, donor countries agreed in 2001 on the "Recommendation on Untying Official Development Assistance (ODA)" in the OECD framework. The purpose of that common agreement was and remains that of providing as much untied development funding as possible, thereby rendering international cooperation more efficient and effective. There is agreement in the international community, after all, that this form of public development financing is paternalistic, costly and inefficient.

Obscure pathways into Switzerland

Official figures for untied aid show that so far, Switzerland has a good record compared to other countries. According to an OECD analysis, 3% of the funds provided by Switzerland in 2021 and 2022 was tied. Yet, the picture presented by the analysis is an incomplete one, as the figure only includes funds that were formally tied. There are, however, also informal ways of giving preference to domestic providers. The pool of candidates can be controlled, for example, by means of the language used in the tender, the financial scale of the projects or the choice of communication channel.

There is no precise overview of the extent of informally tied aid. However, procurement statistics can form the basis for estimating the portion of the funds up for tender that goes to domestic providers. Assessments by Eurodad, the European Network on Debt and Development, show that 52% of all untied funds were awarded to donor country suppliers in 2018 – this being the most recent data available. At 51%, Switzerland is about average. Overall, only 11% went directly to suppliers in partner countries.

Untied aid had long been free of controversy in Switzerland. The current draft of the International Cooperation Strategy (IC strategy) 2025-2028 states: "It [IC] is in line with international trade law, which aims to prevent trade-distorting subsidies in favour of Swiss companies. […] Switzerland takes account of the content of the OECD-DAC Recommendation on Untying Official Development Assistance". Yet, in the light of the decisions regarding Ukraine funds going to Swiss companies, this affirmation seems to be playing to the gallery, for just weeks after the publication of the IC strategy, the Federal Council wrote in a press release: "The Swiss private sector is to play a key role in Ukraine's recovery." This project also signals Switzerland's intention to formally reintroduce tied aid (see also here).

(Un)controversial core contributions

Under OECD guidelines, core contributions to non-governmental organisations from donor countries are not regarded as tied aid, as NGOs operate in the public interest and on a non-profit basis. Internationally, however, this preference is controversial. In recent months, the international #ShiftThePower movement has called for more development funds to go directly to organisations in the Global South. While this call is entirely justified, a more detailed look at how funds can reach partner organisations in the Global South is warranted. The fact is that putting more projects and programmes up for international tender does not automatically mean that organisations in the Global South will win bids. It is therefore crucial to ensure that award processes are created that pave the way for smaller organisations in the Global South to receive core funding and not remain in the role of project implementation partners. Swiss NGOs in particular, all of which have long-standing, solid and trusting partnerships with countless organisations in the Global South, play a crucial bridging function in this context.

Going forward on an equal footing

Many countries make no secret of the fact that they tie their development funding to foreign policy interests. Carsten Staur, the Danish Chair of OECD Development Assistance Committee, said in an interview in 2022 that there has never been any official development assistance in history that has not pursued foreign and security policy aims in one way or another.

Interestingly, those calling for tied aid in Switzerland are the very same political parties that otherwise champion liberal trade rules. But suddenly these rules are no longer to apply to IC. Moreover, such policy decisions mean that those claiming that international cooperation is not effective are in part responsible for the possibility that international cooperation funds may be deployed less efficiently.

If cooperation is to be sustainable and effective and is to take place on an equal footing, partner countries must be able to shape their own development paths. Believing that we in Switzerland should determine what partner countries "need" is failing to do justice to the international debates on forward-looking international cooperation. It should also be clear that tied aid is inefficient and costly. It is therefore high time once again to abandon this approach and invest in long-term partnerships on an equal footing.

The term "tied aid" describes a situation where the provision of funds is made conditional on the purchase of goods and services from suppliers in the donor country. But other forms of conditionality also exist, such as stipulations by donor countries regarding anti-corruption measures, free trade and deregulation policies, or the observance of democratic principles. Attaching conditionality to development funds is also a strategic tool with which to pursue foreign policy goals in the countries of the Global South. This is rarely well received in partner countries, however, as it interferes with their right of self-determination. This in part explains the popularity of new donor countries like China, which make few or no stipulations at all.

Share post now

global

The Alliance Sud magazine analyses and comments on Switzerland's foreign and development policies. "global" is published four times a year (in german and french) and can be subscribed to free of charge.

Climate policy

Trade in carbon certificates – more apparent than real?

03.12.2024, Climate justice

Whether in regard to the CO2 Act or the new austerity programme: Swiss policymakers are relying increasingly on carbon certificates from abroad to meet their own climate target by 2030. Yet the plan could fail – the first programmes are already showing serious shortcomings. An analysis by Delia Berner

Old buses and ubiquitous face masks: Bangkok suffers from exhaust fumes, but do e-buses financed by Switzerland really help in Thailand? © Benson Truong / Shutterstock

In January 2024, Switzerland captured the world's attention – at least in the specialised world of the carbon markets. This was because, for the very first time, carbon emission reductions had been transferred in the form of certificates from one country to another under the new market mechanism in the Paris Climate Agreement. More specifically, Thailand had introduced electric buses in Bangkok and had reduced carbon emissions by around 2000 tonnes in the first year. Switzerland bought this reduction in order to count it towards its own climate target.

Let us take a step back: Switzerland plans, by 2030, to save more than 30 million tonnes of CO2 abroad rather than in Switzerland. The first bilateral agreements in that regard were concluded in the autumn of 2020, and their number has now surpassed a dozen. Several other projects are being developed, ranging from biogas facilities and efficient cooking stoves in the poorest countries, to climate-friendly cooling systems, and also to energy efficiency in buildings and industry. So far, only two programmes have been approved for attribution towards Switzerland's climate target. And the 2000 tonnes of CO2 savings from Thailand were in fact the first certificates to be traded. This means that much remains to be done by 2030 if there is to be a sufficient number of certificates available for purchase by Switzerland.

The first project could fail...

After inspecting case documents under the Freedom of Information Act, the "Beobachter" newspaper has now revealed that the very first programme in Bangkok is at risk of failing to generate any further certificates. Already a year ago, allegations began reaching the Federal Office for the Environment (FOEN) to the effect that the e-bus manufacturing company was violating national labour law and the right to the freedom of association enshrined in human rights law. Although a provisional agreement was reached a year ago, new allegations apparently surfaced this year, which the FOEN must now investigate. This is so because Switzerland cannot approve certificates if human rights violations were entailed in generating them. The FOEN was quoted in the "Beobachter" to the effect that it "can and will" suspend further issuance of certificates if the allegations are substantiated. Extensive investigation by the "Republik" magazine has brought yet more allegations to light. Supposedly, Switzerland was even implicated in an economic crime in Thailand by fuelling a 10-billion-franc stock market bubble and ignoring warnings.

The second approved project, too, will generate fewer certificates than promised. A new research by Alliance Sud into the cooking stove project in Ghana reveals that its planning entailed over-estimating emission reductions by as much as 1.4 million tonnes.

It is now already clear that, in general, foreign offsets are no cheaper and certainly no easier to implement than climate protection measures in Switzerland. The latter will have to be introduced sooner or later anyway in order to achieve the net zero target in Switzerland.

More than growing pains

The first projects illustrate the difficulties being encountered in ensuring that a project effectively reduces carbon emissions by a particular amount and is also cost-effective. Doubts surrounding reductions have been the reason why many offset projects have made the headlines in recent years. Cost effectiveness is crucial, as the majority of the certificates are paid for by the Swiss public through a tax on fuel. To verify these two things, the FOEN would need to examine the projects' financial plans. It would have to be persuaded, for example, that project costs include no disproportionate margins or profits, but that as much money as possible is being invested in climate protection or sustainable development, with the involvement of the concerned population groups in the partner country.

Yet the flaws of the Swiss system of foreign offsets are becoming apparent here. Because the certificates are not bought by the Confederation but by the Foundation for Climate Protection and Carbon Offset, Klik, which converts the proceeds from the fuel tax into certificates, the "commercial details" are not revealed to the public. What this means is that no one knows the cost of saving a tonne of carbon emissions by using e-buses in Bangkok, or the overall amount of money being invested in the cooking stove project in Ghana – let alone what the yields accruing to private market participants look like. Moreover, in the case of the aforementioned project in Ghana, extensive passages were redacted in the project documentation that was published. The transparency is even worse than in the case of serious standards in the voluntary carbon market.

Twofold need for action

These challenges go beyond mere teething problems and reveal a twofold need for action by Swiss lawmakers. First, the lack of transparency regarding project-related financial information in the ordinance on the CO2 Act must be remedied. The ordinance is currently being aligned with the latest revision of the Act. Second, the image of foreign offsets as a cheaper and simpler path to climate protection must be corrected. Switzerland must move ahead with climate protection within its borders and again achieve climate goals after 2030 without carbon offsets. Alliance Sud calls on the Federal Council to incorporate this into the CO2 Act after 2030.

Share post now

Trade and climate

Carbon border taxes must not penalise poor countries

03.12.2024, Climate justice, Trade and investments

Imports of the most polluting products are to be taxed under the European Union's Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM). No exemption is being contemplated for the poorest countries, even though they will be severely affected. Should Switzerland ever adopt this measure, it would have to make sure to put this right.

One of the world's largest uranium ore mines closed in Akokan, Niger. However, more are planned in the crisis-ridden north and are economically significant. © Keystone / AFP / Olympia de Maismont

The European Union (EU) takes its climate commitments seriously. In 2019, it launched the European Green Deal, designed to cut CO2 emissions by 55% by 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality by 2050. The programme encompasses a number of internal and external policy measures, including the European Union Deforestation Regulation (EUDR, see global #92). Another key European trade policy project is the CBAM, or Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism. Its purpose is to make importing industries subject to the same rules as polluting European enterprises. The latter must observe a cap on emissions, which, by the way, they can trade on the "carbon market" in order to comply with the limits set. These measures are designed to render investment in clean energy in Europe cheaper and more attractive. "The CBAM will encourage global industry to adopt greener technologies," European Commissioner for Economic Affairs Paolo Gentiloni has said.

Avoiding carbon leakages

Brussels adopted the CBAM in order to prevent production from moving to countries where the price of carbon is lower than in the EU, or even zero (known as "carbon leakages"), or to shield European producers from unfair competition. Under this mechanism, imports of particularly polluting products will be taxed at the border, starting with iron and steel, cement, fertilisers, aluminium, hydrogen and electricity. It took effect in the EU on 1 October 2023 and is being implemented in successive phases; the mechanism will be fully deployed as of 2026. Starting in 2031, it is expected to cover all imports.

Poorer countries affected

The fundamental question is whether the measure is effective. The EU is optimistic. It estimates that its emissions will decline by 13.8% by 2030, while those of the rest of the world will be down by 0.3% compared with 1990. But the approach elicits sharp criticism from the countries of the Global South, which assert that it is negatively impacting their development. Others criticise it for failing to provide a general waiver, at least for the poorest countries. Moreover, UN Trade and Development (UNCTAD) has calculated that the impact on climate is expected to be minimal: the CBAM will reduce global CO2 emissions by a mere 0.1%, while EU emissions will diminish by 0.9%. It is nonetheless expected to boost the revenue accruing to developed countries by USD 2.5 billion while reducing the revenue going to developing countries by USD 5.9 billion.

In 2022, ministers from Brazil, South Africa, India and China called for discriminatory measures such as carbon taxes at borders to be avoided. The countries most affected by this mechanism are the emerging countries that are the leading exporters of steel and aluminium to Europe, namely, Russia, Turkey, China, India, South Africa and the United Arab Emirates. But Least Developed Countries (LDCs, a category created by the United Nations) such as Mozambique (aluminium) and Niger (uranium ore) will also be impacted. The welfare losses to developing countries like Ukraine, Egypt, Mozambique and Turkey are put at EUR 1–5 billion, a substantial amount considering their gross domestic product (GDP).

An exemption for LDCs

Let us take Africa, which is home to 33 of the 46 LDCs. A recent study by the London School of Economics concludes that if the CBAM were applied to all imports, Africa's GDP would contract by 1.12% or EUR 25 billion. Aluminium exports would decline by 13.9%, iron and steel by 8.2%, fertilisers by 3.9%, and cement by 3.1%. So, should the baby be thrown out with the bathwater and the CBAM declared to be anti-development? Probably not. The Belgian NGO 11.11.11. proposes that the least developed countries be exempted from this mechanism, at least initially, under WTO rules; or that they be taxed less than the others. When the CBAM was being discussed in Brussels, this possibility was considered then jettisoned by the Parliament, as the EU opted to secure more revenue. UN Trade and Development suggests returning the revenue from the mechanism to the LDCs to fund their climate transition. The EU is expected to garner revenue of EUR 2.1 billion, which could be channelled multilaterally via the Green Climate Fund, itself currently underfunded.

No CBAM in Switzerland for the time being

For now, there is nothing of the kind in Switzerland. Goods originating in Switzerland and exported to the EU are currently exempt from the CBAM by virtue of the Emissions Trading System (ETS), and the Federal Council has opted not to introduce any such mechanism for products being imported into Switzerland. The ETS represents the maximum amount of emissions available to industries in a particular economic sector. Each participant is allocated a certain quantity of emission rights. If their emissions remain below this limit, they may sell their rights. If they exceed the limit, they may purchase rights.

A parliamentary initiative was submitted to the National Council in March 2021 calling on Switzerland to amend the CO2 Act to include a border carbon adjustment mechanism, taking account of developments in the EU. Currently, that parliamentary initiative is still being discussed in the committees. The CBAM could be an effective trade measure for reducing imported CO2 emissions. But should Switzerland ever adopt it, it would have to make sure not to penalise the poorest countries, instead granting them exemptions, and returning a substantial part of the accrued revenue to assist them in making the energy transition.

International trade accounts for 27% of emissions

Greenhouse gas emissions generated by the production and transport of exported and imported goods and services account for 27% of global greenhouse gas emissions. According to the OECD, these emissions come from seven economic sectors, namely, mining and energy production, textiles and leather, non-metallic chemicals and mining products, base metals, electronic and electrical products, machinery, vehicles and semiconductors.

Action is undoubtedly needed on both the trade and production fronts – on the production front, for example, by promoting green technologies, technology transfer and climate finance. On the trade side, through other measures such as the CBAM, though without penalising poor countries. The latter must be assisted in managing their ecological transition and adapting to the new standards.

Share post now

global

The Alliance Sud magazine analyses and comments on Switzerland's foreign and development policies. "global" is published four times a year (in german and french) and can be subscribed to free of charge.

International Tax Policy

"The system is set up against us"

29.11.2024, Finance and tax policy

Everlyn Muendo is following the UN negotiations for a framework convention for international cooperation in tax matters on behalf of the Tax Justice Network Africa (TJNA). In this interview, she analyses the current developments in the process in New York and explains why there is no longer any alternative to the UN for the Global South when it comes to international tax policy. Interview: Dominik Gross

Tax revenue is flowing to the north, the cost of living is rising: Violent protests against unjust fiscal policy reforms have been shaking Kenya since June. © Keystone / AFP / Kabir Dhanji

Alliance Sud: Everlyn Muendo, you participated in the negotiation sessions for a UN framework on international tax cooperation in New York this year. What is your general impression of this process so far?

We experienced a very clear and sharp political divide in terms of the positions between the Global North and the Global South. Overall, through all the sessions, we could clearly see what the positions of the Global North and of the Global South were.

The transparency of the negotiations is already a big step forward compared to those in previous years at the OECD in Paris. Where do you see the major issues resulting in this divide between North and South?

I would summarize the positions of the Global North into the following issues. Firstly, they think that the UN framework convention should play a complementary role to the OECD and shouldn’t – as they call it – duplicate its work in the field of international tax cooperation. So obviously the work of the OECD in this field. Secondly, their goal seems to be to diminish the role of the UN only to capacity building, which means to offer support in terms of infrastructure and expert education for tax administrations in the Global South. This is the result of a profound misperception of the situation of the Global South: They seem to think that we don’t have adequate capacities. In their view this is the reason for the international tax system not being inclusive or effective. This is a disingenuous argument, because even during the inclusive framework process of the OECD some developing countries articulated substantive and significant concerns about the overall direction of the global minimum tax and the redistribution of taxing rights to market countries. But those concerns were constantly ignored.

In the UN framework convention process, the countries of the Global South are strongly pushing to address the systemic issues.

How were these concerns ignored?

For instance, developing countries were obviously not comfortable with setting the minimum tax rate to fifteen percent. We wanted a much higher rate. But we still ended up there. Some countries went as far as rejecting the so called Two Pillar Solution of the OECD back in 2021. These were Nigeria, Kenya, Sri Lanka and Pakistan. But still, nothing was substantially done to change the way these proposals were framed. That’s why I think it is very disingenuous to say it is a capacity issue. It is the substantive rule making that needs to be changed. As I said in my statement during the negotiations in April in New York, you can’t capacity build us out of imbalanced taxing rights. In the UN framework convention process, the countries of the Global South are strongly pushing to address those systemic issues.

So, countries of the Global North are trying to avoid the crucial issues in this process?

Yes, I think so. My impression is that they are not negotiating honestly. But in international negotiations it is a fundamental principle that both parties are supposed to negotiate in good faith. They are also obligated to implement the treaties and the obligations that they have agreed on in good faith. For instance, to say that we need more technical analyses, does not build confidence. We have the UN secretary general’s tax report on the status of international tax cooperation, which was particularly looking at how the lack of inclusiveness in international tax cooperation is making international tax cooperation ineffective. So, we have proof of our arguments, it’s all there.

How is the coordination between African countries working?

I think the Africa Group is doing its best with the limited resources that are available, both on the human and the technical level. I think we also have seen a lot of great leadership from the African Union commission and the Pan African bodies – the UNECA (UN Economic Commission for Africa) and the ATAF (African Tax Administration Forum) – in organizing and informing African countries of what is at stake at the UN.

Everlyn Muendo

Kenyan Everlyn Muendo is a lawyer at the Tax Justice Network Africa (TJNA). She works on the question of how international tax policy influences development financing in African countries.

How can we as a global civil society coalition best challenge the position of the EU or Switzerland speaking off “duplication” and “capacity building”?

First, it just needs to be acknowledged, that the OECD initiatives and processes such as the development of the automatic exchange of information or the one of the minimum tax for multinationals are not working for a significant group of people, particularly in countries of the Global South. That’s why they are seeking to create another forum for international tax cooperation which should be inclusive. This is clearly defined in the UN resolutions on which the process has been based since 2022. Secondly, there is no other universal initiative on global tax cooperation. Some may say we could regard most of the work which has been done at the OECD as regional level work. The question is then what would be the criteria for picking and leaving certain aspects of what has been done. For example, Pillar 1 of the OECD BEPS II project which is supposed to be about reallocation of taxing rights will probably never be completed. These aren’t issues which we can give more time to.

Countries agreed on the Terms of Reference of the convention with a 2/3 majority. What is at stake now?

Tax is such a critical issue when it comes to financing for development. It is not just about technical issues like profit allocation rules or the division of taxing rights. It is about building up decent education systems for all or about fighting the public health crisis in the Global South. The reason for the dramatic problems in both fields is a constant underfunding of public services in those countries. At the end it’s about human beings. Our inaction brings about victims and that’s why we really want to move forward with this process. It is also about generating resources to finance climate protection. Although we – compared to the Global North – contributed very little to the climate crisis, we are severely affected by it.

On the African continent you can’t speak about international taxation without speaking about taxation of natural resources, particularly those of the extractive sector.

What would be the key solutions for resource-rich countries in Africa?

On the African continent you can’t speak about international taxation without speaking about taxation of natural resources, particularly those of the extractive sector. Most multinational enterprises within the continent are part of the extractive industry. But their headquarters are obviously in developed countries. It’s actually a very complicated issue and goes way back into our colonial history. Before colonialists left, they made sure that even after independence our economies would be structured in a way that benefits them the most. So, instead of building up food security for instance, our economies have been structured in such a way that we would essentially continue to produce coffee, tea, crops and commodities that are of most value to developed countries. Essentially, we export all these raw materials, and the added value is made outside the continent. On the other side all the final products resulting from industrial production in the Global North based on our raw materials are then sold back to us. We don’t gain as much as we should from our own resources in comparison to countries who don’t have these commodities at all.

Can you give us an example?

Which country is known for good chocolate? It’s not Ghana.

Switzerland?

Exactly! This is a striking fact if you consider that over half of the cocoa beans imported into Switzerland comes from Ghana. Because of harmful tax practices and aggressive tax planning by multinationals hundreds of billions of dollars in profits are shifted away from African countries. Even with the economic activities which foreign companies are carrying out and the income they’re generating through our resources we don’t get our fair share of taxes. Instead, the tax revenues go primarily to the residence countries of the multinationals. The system is really set up against us.

It will take some time until new UN rules based on a future framework convention will bear fruit. Are there current opportunities for improvement outside this process?

We are also fighting for more bilateral double tax treaties based on the UN model rules which are much better than their counterparts at the OECD, but we haven’t been so successful with that. By nature, a single country from the Global North has a lot of power when it comes to negotiating a bilateral agreement. And some of those countries are bullies! The imbalance of economic power really plays out here. So even if African or developing countries in general do have a lot of capacity, they still end up giving away a lot of our taxing rights. That is happening because we feel the pressure that we still must attract foreign direct investment from a partner country to fuel economic development. I like to call that the FDI fallacy in Africa.

Everlyn Muendo at a discussion of the Tax Justice Network Africa on tax and climate justice this November in Nairobi. © TJNA

The Kenyan society faces huge tensions because of a recent new finance bill issued by the national government. Can you explain what is happening there?

The June 2025 Finance Bill protests were bigger than the Finance Bill itself. They were an expression of the frustration of hardworking Kenyans with the increasing economic injustices. The Kenyan government is highly indebted and desperately needs to raise resources for debt servicing and development. But it is introducing taxes that have a heavy bearing on the cost of living. These include a proposed eco-levy, a motor vehicle tax, increased road maintenance levies and removing VAT exemptions on certain crucial items, amongst others. These taxes are highly regressive yet at the same time, we receive very little value for our money in terms of public services. The bulk of the revenue is spent on debt servicing, which can take up more than 50% of the revenue, and on corruption which crowds out critical public services.

What are the consequences?

There is a breakdown of public services such as health and education. For instance, there have been severe pay cuts for public servants such as medical interns whose salaries were reduced. Additionally, a new university funding model was introduced. This model skyrocketed university fees leading to a huge public outcry. Kenya has become a hub for experimentation on fiscal consolidation measures. Ordinary Kenyans are losing twice!

How can you – as Switzerland - talk about corruption in the African continent, while you are the biggest enabler of secrecy perpetrating illicit financial flows?

What do you say to the accusation, that more public revenue in African countries would disappear due to corruption anyway?

How can you – as Switzerland - talk about corruption in the African continent, while you are the biggest enabler of secrecy perpetrating illicit financial flows? Seriously, all I can say, it needs two to tango. On the one hand there is an African official who is corrupt, but who is giving him the bribe? A lot of corporations! We had Glencore from Switzerland. The corruption cases this corporation has been involved in are very telling. We also must recognize the role secrecy jurisdictions like Switzerland have played in this by being a haven for these corrupt individuals and officials in our countries. That’s why a lot of this wealth is held offshore. Nobody says, oh I am going to hide my money in Kenya. No! It’s Switzerland! You are infamous for a reason!

How is all this related to tax avoidance of multinationals?

Aggressive tax planning and corruption are the same. They are both immoral, they both have the same overall effect of bleeding out resources. But one is legal, one is not. And this is why you find a lot of African countries that prefer using the term illicit financial flows (IFFs), where we are grouping all these activities together and trying to produce a continental level strategy to address it – whether they are legitimated by law or not. Particularly the commission of the African Union is doing a lot in this regard with the support of the UN.

Let us get back to the UN. The next negotiations are due in February 2025. Could the positions of the Global North change?

Well, there are two interesting developments in this regard: Firstly, the EU states abstained in the vote on the key elements of the convention in August instead of voting no, as they did on the previous resolutions. This is a sign that the Global North's extraordinarily strong skepticism towards the process itself is easing. That could have a positive impact on the next rounds of negotiations. Secondly, Donald Trump's victory in the US presidential elections could lead to the USA completely blocking both OECD and UN processes. Up to now, the countries of the North have always said that decisions at the UN need to be made by consensus. However, I think that they will now have to adjust this position in view of the developments in the USA.

Going to the UN is our way of addressing fundamental challenges.

What would you like to change?

Wouldn't it be better to be satisfied with simple majority decisions, even if consensus is the ideal? Sometimes things just do not go according to your own ideal. Instead of being held back by a single country or a small group of countries, it would be more democratic to allow everyone else – whether from the Global North or the Global South – to move forward. However, if decisions are made by consensus, the USA, as the economically strongest country, has a virtual veto power. It would be much more democratic to give every country an equal vote in majority decisions.

Where do you see positive developments on the African continent?

In several African countries we see a political process today, in which people push for stronger accountability systems of our own leaders, politically and economically. Especially in West Africa, for example in Senegal. The uprisings we have recently experienced there showed to a certain extent also an extreme expression of the desire for self-determination in societies which we can still call postcolonial. No matter if you look from trade to debt to tax to whatever: we may have political sovereignty, we may be recognized states by international law, but we are far from economic sovereignty. Going to the UN is our way of addressing those fundamental challenges because tax sovereignty is a very crucial part of economic sovereignty overall.

Share post now

global

The Alliance Sud magazine analyses and comments on Switzerland's foreign and development policies. "global" is published four times a year (in german and french) and can be subscribed to free of charge.

Investigation

Switzerland in the dense fog of carbon offsetting

20.11.2024, Climate justice

With the purchase of new cookstoves, Ghana is expected to save more than 3 million tonnes of carbon emissions, thanks mainly to women – as a substitute for emission mitigation in Switzerland. Alliance Sud criticises the project's glaring lack of transparency and highlights controversial details that project owners attempted to hide from public view.

A girl cooks with her mother in her home in Tinguri, Ghana.

© Keystone / Robert Harding / Ben Langdon Photography

Grace Adongo, a farmer from Ghana's Ashanti region, is happy with her new and more efficient cookstove. Instead of cooking on an open fire, she now places the pot on a small stove. She needs appreciably less charcoal, which both saves money and mitigates carbon emissions. This testimonial comes from the latest Annual Report of the Ghana Carbon Market Office and coincides with many others that are reporting on the numerous cookstove projects throughout the global carbon market. These projects supposedly help provide poorer population groups with cookstoves that are more efficient and less harmful to health than traditional stoves or fireplaces, which generate large amounts of smoke. This reduces wood consumption and carbon dioxide emissions (how much is highly controversial – but more on that later).

The principle involved is always similar. The cookstoves are sold cheaply. This entails customers transferring to project owners their rights to the emission mitigation outcomes. The emissions saved by the new stoves are then calculated over the ensuing years and sold internationally by the project owner as carbon certificates. The proceeds from the certificates are needed to subsidise the cookstoves.

From the personal standpoint of people like Mrs. Adongo, what sounds like a good thing is also precisely that. But the system as a whole is much more multilayered and contradictory. The case mentioned at the start, the Transformative Cookstove Activity in Rural Ghana, which Alliance Sud examines in detail in this paper, revolves around the government carbon offset market in which Switzerland imputes the emission mitigation outcomes achieved in Ghana to its own climate goals. A surprising number of venues also come to light in the process, and also warrant critical assessment from the standpoint of climate justice. Switzerland's cooperation with Ghana is also a good example of why the trade in certificates under the Paris Agreement is not conducive to attaining the ambitious climate goals.

Carbon certificates from this and many other projects are being paid for with a 5-centime tax assessed on each litre of fuel at Swiss petrol pumps. Owned by motor fuel importers, the Foundation for Climate Protection and Carbon Offset KliK provides the money for mitigation projects in Switzerland and abroad. Through carbon offsetting abroad, Swiss lawmakers aim to compensate for climate mitigation actions not taken in Switzerland, so that they are still able to meet the climate goals of the Paris Agreement.

Under the 2015 Paris Agreement, Switzerland undertook to halve, by 2030, its greenhouse gas emissions compared to 1990. With the CO2 Act, however, only about 30% of emissions can be mitigated in Switzerland – barely more than before the law was revised in the spring of 2024. The remaining 20% must be offset abroad. Under the Federal Council's savings package announced in September 2024, climate mitigation activities in Switzerland are also expected to diminish. The inevitable consequence is that Switzerland will need more carbon offset certificates if it is still to achieve the climate goals. That is not the meaning of Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, under which the transfer of emission mitigation outcomes to other countries should lead expressly to "higher ambitions". To achieve this, Switzerland will have to ensure that the climate goals of both countries are consistent with the goals of the Paris Agreement. Switzerland has promised net zero by 2050. Because net zero is to be achieved globally by that same year, Switzerland therefore expects other countries also to set their net zero target at 2050. Measured against this yardstick, there are substantial gaps in Ghana's national contribution, up to 2030, towards the realisation of the Paris Agreement. Ghana has announced only a non-binding net zero target for 2060 and excludes oil production from its climate goals. When contacted in that regard, the Federal Office for the Environment (FOEN) writes: "The requirements of the Paris Agreement apply", and points towards the unilaterally set climate goals based on the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capacities. "In the process, climate goals must encompass the highest possible ambition and subsequent goals must be even more ambitious." However, there are no other criteria for the climate goals of a partner country.

A year ago, Ghana announced the expansion of oil production, adducing the lack of financial support for climate protection as the reason. This illustrates the fundamental problem: the countries in the Global South lack the international climate finance that should be forthcoming from the Global North by way of support. The upshot is that they opt for what they see as their second-best solution for raising funds, that of selling the outcomes of their climate mitigation activities as carbon certificates. The difference with climate finance is that Switzerland obtains the "right" to postpone its climate mitigation measures. On balance, ambitions for effective climate mitigation are being lowered, not raised.

Dense fog in February

Ghana and Switzerland approved this cookstove project in February 2024 under the bilateral market mechanism of the Paris Agreement (Art. 6.2). It is being implemented by the Amsterdam-based company ACT Commodities (project owner, see Box 2) and is projected to record a 3-million tonne reduction in carbon emissions by 2030. It is therefore incumbent on both governments to ensure that the project fulfils and maintains high quality requirements, which it promises to do. The Federal Office for the Environment (FOEN) verifies the relevant project documentation and publishes them upon authorization.

The project owner is ACT Commodities, an international conglomerate headquartered in Amsterdam. On its website, the company describes itself as the leading global provider of market-based sustainability solutions that is driving the transition to a sustainable world. ACT is a major player in emissions trading. But the company prefers to avoid too much transparency – its own website fails to mention that the conglomerate also has oil and fuel trading in its portfolio (through its sister company ACT Fuels, which has no website). This comes to light thanks only to a perusal of the Dutch commercial register. Since July 2023, ACT Commodities has also owned a company that supplies marine fuels, the dirtiest of all fuels. The conglomerate is therefore one of a growing group of commodity traders doing business with fossil fuels and simultaneously "greenwashing" themselves as players on the carbon market.

But the very first look at the documents reveals a lack of transparency: the project is as opaque as dense fog. Extensive passages in the project description are redacted, including virtually the entire analysis that is meant to prove that the project will lead to additional emission mitigation (see chart). But many other relevant facts and figures were also concealed. And the document containing the calculations showing why the CO2 reduction should amount to 3.2 million tonnes was not even published in the first place. That is not what transparency looks like.

Alliance Sud requested publication of the unredacted documents and calculations pursuant to the Freedom of Information Act (FoIA) – and had to wait four months owing to the project owner's initial refusal. Much, though not all of the project documentation was released thereafter. The passages that were still redacted were supposedly business secrets. It is now also becoming clear that in the original document, many places had simply been arbitrarily concealed.

Excerpt from the analysis of the project's additionality, originally redacted altogether.

Emission mitigation is being overestimated by up to 79%

The calculation methodology whereby the project in Ghana is expected to save 400,000 tons of carbon emissions annually over eight years is a key piece of information regarding carbon offset projects. Reputable certifiers in the voluntary carbon market require project owners to disclose these calculations. These data must be made available for scientific analysis – especially since a growing number of studies are identifying cases of over-crediting of emission mitigation through carbon certificates, including for cookstove projects.

In this case, however, the project owner is reluctant to do so – an unacceptable lack of transparency. Alliance Sud submitted an FoIA request and obtained a PDF copy of the calculation tables. Without being able to view the integrated Excel formulas, verifiability remains limited.

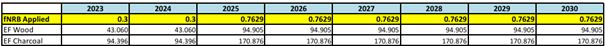

But the figures now available offer surprising revelations. The PDF document containing the calculations shows that for the years 2025-30, emission reductions for the same stoves are being calculated at almost twice as much as for the years 2023-24. The underlying reason is obviously a planned increase of the most key metric, namely, the fraction of non-renewable biomass (fNRB). This is an estimate of the amount of wood biomass by which the harvesting of fuelwood exceeds its natural rate of regeneration. Only reduced use of non-renewable fuelwood can be regarded as a reduction in carbon emissions. The metric is multiplied directly by the other factors and is therefore crucial to calculating emission mitigation. The overstating of the fraction of non-renewable biomass (fNRB) is the main reason for the sometimes-scathing criticism elicited by cookstove projects launched to date for emission mitigation purposes.

For anyone keen on the details, the project documentation showed an fNRB set at 0.3, which is more conservative than for many previous cookstove projects. According to the official UNFCCC reference study dated June 2024, this is an appropriate standard value, as it avoids massively overstating emission mitigation and is also consistent with the country-specific value contained in the study for Ghana, which is 0.33. However, the project now has a clause enabling Ghana and Switzerland bilaterally to adjust the fNRB retrospectively (upwards). The fact that concrete calculations are already being done, from 2025 onwards, on the basis of an fNRB of 0.7629 only comes to light from the PDF document containing the calculations, which was not originally published. The project description fails to mention that plans are already being laid using a higher value, even though it is still to be validated. The value 0.7629 comes from the outdated "CDM tool 30" which is deemed by the FOEN itself to be insufficient as a basis. In the spring of 2024, Ghana invited tenders for an independent study to determine a country-specific fNRB value for Ghana – obviously in the hope that a markedly higher value can be validated. If Switzerland is also to accept it, the study must pass the peer review by UNFCCC bodies. In the light of the aforementioned widely accepted reference study which calculates a country value of 0.33 for Ghana, that is likely to be an uphill task.

A look at the calculation document shows that as of 2025, calculations are to be based on an fNRB – the most important metric – more than two times higher (line in yellow). According to Alliance Sud calculations, this means that between 2025 and 2030, emission mitigation will be overestimated by up to 92%. All told, the overestimation is up to 79% (using the correct calculation for 2023 and 2024).

If a baseline fNRB value more than twice as high is applied, with no basis whatsoever, emission mitigation is being overestimated from the outset. According to Alliance Sud calculations, the project would reduce carbon emissions by 1.8 million tonnes at the most, if the fNRB value is held constant at the more realistic level of 0.3. But the project promises a reduction of 3.2 million tonnes of carbon emissions. It thus overestimates overall mitigation by up to 79%.

Some research lifts the fog…

The absurdity of attempting to describe half of the project documentation as "business secrets" (in the first version of February) is clear from the fact that much of the concealed information is publicly available in other places. If few more minor items of information that had originally been concealed are even available elsewhere in the same document. Further information can be gleaned from Ghanaian Government documents, or can be deduced from other sources.

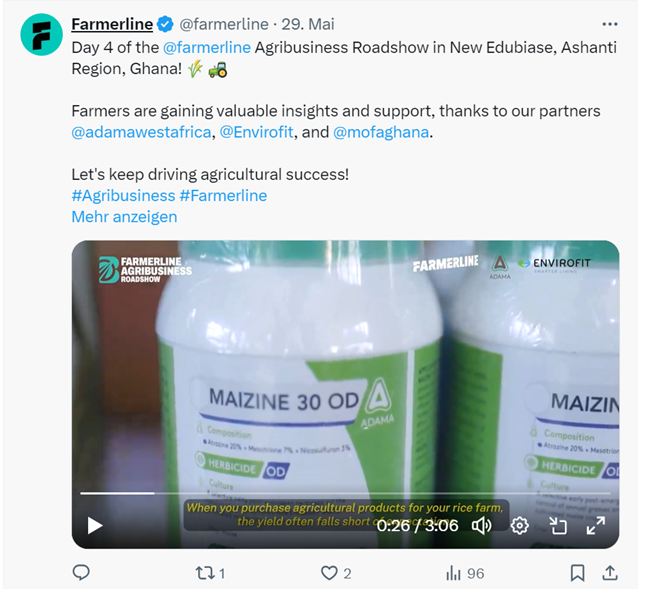

For example, from an online article by the Ghanaian authorities about a visit by the KliK Board of Directors, we learn who is the project's main distributing partner in Ghana – a Ghanaian company called "Farmerline". Farmerline facilitates access for farmers to agricultural inputs, thereby opening up the global agricultural industry to many new clients from Ghana. The project owner also attempted to conceal this connection. Several references to partnerships in the agriculture sector had originally been hidden in the project documentation, and specific cooperation is still redacted. There are reasons, as a closer look will show.

...lingering pesticide spray

In June 2023, Farmerline announced its cooperation with Envirofit, the cookstove producer and the project owner's implementing partner. The project documentation also describes plans to sell 180,000 stoves to rural dwellers within a short space of time, and notes that the stoves will be available at more than 400 businesses for agricultural inputs. But some posts by Farmerline on the "X" platform do arrest the attention of readers. This year, Farmerline conducted an "Agribusiness roadshow" across various regions of Ghana in cooperation with Envirofit – and with the crop protection company Adama, a member of the Syngenta Group. On each day of the roadshow, farmers were presented with the efficient Envirofit cookstoves and Adama pesticides, both being put up for sale. Adama products are identifiable in the Farmerline videos, including three insecticides and one herbicide containing active substances banned in Switzerland and the EU because of their toxicity to the environment and human health. They are atrazine, diazinon, and bifenthrin. Atrazine pollutes groundwater, hampers photosynthesis in plants and is virtually impossible to remove from the environment; it is also classified as a carcinogen. Diazinon attacks not only the pests being targeted but all insects and can also be highly toxic to humans if it comes into contact with the skin. Bifenthrin poses a danger mainly to aquatic animals but should also not be inhaled by humans (see the Pesticide database maintained by Pesticide Action Network).

Sample photo from a Farmerline roadshow video in which the herbicide Maizine 30 OD containing the active substance atrazine – banned in Europe – is also being sold alongside cookstoves.

Furthermore, none of the videos contains a demonstration or the sale of appropriate protective clothing. According to various studies (Demi und Sicchia 2021; Boateng et al 2022; and others), the growing use of pesticides in Ghanaian agriculture is leading to considerable health problems for farmers. In the absence of instructions from dealers, many either do not know how to use the pesticides properly and protect themselves in the process, or they lack sufficient funds to be able to afford protective clothing. Besides, they obtain expert information mostly from their personal circles or from some dealers, but no independent agricultural advice is available. In their study, Imoro et al. 2019 found that 50% used no protective clothing at all and another 40% were not sufficiently protected. Asked whether protective clothing was also being sold at the roadshows, KliK replied that the highest standards of sustainability were of course a prerequisite for their cooperation partners. KliK writes that the issues raised by Alliance Sud with this question lie outside the scope of its discretion.

Thus, attempting to obtain a clear statement regarding the benefits of this offset project for sustainable development is still akin to stumbling around in the dark. Cookstove customers will indeed save money and, as there is less smoke, also hopefully improve their health. Yet, they are simultaneously being urged to spend the money saved on pesticides, the increased use of which is damaging the environment and also creating new health problems in many instances. From this perspective, KliK's assessment of its cooperation partners' "highest standards of sustainability" is erroneous. It is indeed reasonable to strive for synergies with existing players in the agriculture sector in order to reach rural dwellers. But had sustainability been the uppermost concern, a partnership with organisations that promote agroecological approaches would much more likely have suggested itself.

Eye-watering profits for investors

While the new cookstoves enable customers to make financial savings, the project is financially worthwhile for the investors on a much larger scale. It lacks transparency also from a financial standpoint in that the pricing of the stoves is redacted, and the prices of the certificates are a private matter for KliK and its business partners. Moreover, the FOEN is not reviewing a financial plan or anything similar for the project. Yet, from the additional information released following the FoIA request, it is clear that investors are likely to rake in handsome profits. The investors behind this project are invisible, but according to project documentation, can expect an annual return of 19.75% on their investment. A comparison is being drawn with Ghanaian government bonds in order to justify this absurd return. That comparison holds no water whatsoever, as the one thing has nothing to do with the other. The risks associated with investing in a government bond issued by an already highly indebted country are of an entirely different nature – which accounts for the high yields (although it does not legitimise them, as the high interest rates for poor countries are horrific and catastrophic – but again, that is another story).

What this case involves, in contrast, is a project partly financed and secured with quasi-public funds; this could be classified as blended finance, a mix of public and private financing. This is so because fuel importers collect a levy on fuel, by virtue of the CO2 Act. At a purely technical level, should the proceeds of this levy pass through government coffers – as other levies generally do – before being disbursed for carbon offset projects, that would make them taxpayers' money.

That would give rise to a public interest in ensuring that the proceeds from this levy are used efficiently. The funds must go towards climate mitigation and sustainable development in the country concerned, not towards gold-plated returns for investors.

Conclusion

Efficient cookstoves are an inexpensive way of improving the lives of many people while mitigating greenhouse gas emissions. Yet, there are considerable contradictions lurking in the market mechanism under the Paris Agreement when implementing climate mitigation projects in the Global South. It is meant to promote sustainable development locally, but is conceived as potentially lucrative business for investors. And while some emissions are being reduced in the Global South, the mechanism offers a political pretext for postponing climate mitigation activities in a country as rich as Switzerland.

Transparency in the certificate trade is therefore the key to discovering the multilayered and potentially problematic background to carbon offset projects. Switzerland's carbon mitigation project in Ghana is a telling example of this. Neither the overestimation of emission mitigation, the sale of toxic pesticides nor the exorbitant yields could be gleaned from the documents that were published following the authorization of the cookstove project. It was only through an FoIA request and further investigation that Alliance Sud was able to clear the fog of non-transparency shrouding the project documentation: what came to light was the approval of reckless calculation methods, business practices by implementing partners inimical to the environment and to people, and a questionable interpretation of transparency by the main players. However, the possibility of public scrutiny remains crucial to ensuring that carbon mitigation projects do not endanger implementation of the Paris Agreement.

This case is the second carbon offset project by Switzerland under the Paris Agreement to be looked into by Alliance Sud. A year ago, Alliance Sud and Fastenaktion elucidated the reasons why new E-buses in Bangkok are no substitute for climate mitigation activities in Switzerland.

Share post now

EU deforestation regulation

Green colonialism or development opportunity?

21.06.2024, Trade and investments

A new regulation prohibits the import into the EU of the seven products most linked to deforestation. There must be no harm to small producers in the South.

A single green tree in the burnt and deforested landscape near Mae Chaem, northern Thailand.

© Keystone / EPA / Barbara Walton

The new European Union Deforestation Regulation (EUDR) will take full effect on 1 January 2025. Imports into the European Union (EU) of the seven commodities that contribute most to the death of forests – cocoa, coffee, palm oil, rubber, soya, wood, cattle – and their derived products such as chocolate, coffee capsules, furniture, paper, tyres, for example, will only be allowed if it is demonstrated that they originate from land that was not deforested after 1 January 2020. They must also respect labour rights, anti-corruption standards and the rights of indigenous peoples, among other things.

For those purposes, producing countries will be divided into three categories based on the risk of deforestation, and production sites will be monitored by sophisticated technology, including geo-tracking. The initiative forms part of the EU Green Deal, which is based on an incontrovertible finding: after China, the Twenty-seven are the main importers of products that contribute to the deforestation linked to international trade. Due diligence, i. e., ensuring the absence of deforestation, must be carried out by all players in the supply chain – producers, exporters and importers large and small, with more or less stringent conditionalities, depending on size.

The NGO Fern (Forests and the European Union Resource Network) takes the view that the regulation could also affect Honduras, Ghana and Cameroon, which are countries especially dependent on exports to the EU.

Countries of the Global South opposed to the EUDR

The countries of the Global South are steadfastly opposed to this initiative, which they view as disguised protectionism and a new green colonialism. In September 2023, 17 Heads of Government of Latin America, Africa and Asia sent a letter to the Presidents of the European Commission, European Parliament and Council of Ministers deploring the "one-size-fits-all" approach of the EUDR and the fact that it ignores the different local conditions.

Smallholders and small-scale producers, in particular, will find it extremely difficult to prove their compliance with the requirements, even though, except for a few products like coffee and cocoa, it is mainly the large producers and exporters who are able to place their products on European markets.

The negative impacts of this initiative were not long in coming. As highlighted by the International Institute for Environment and Development, European importers are already turning away from Ethiopian coffee and instead towards Brazilian coffee, which is much more traceable.

In its Trade and Development Report 2023, UN Trade and Development (formerly UNCTAD) expressed concern over the proliferation of unilateral initiatives like the EUDR and the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) – the carbon tax at the border also imposed by the EU on highly polluting products such as aluminium. They are seen as violating the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities enshrined in the Paris Climate Agreement.

The example of Thailand

Krungsri Research View looked specifically at the case of Thailand, which demonstrates the ambivalent nature of the impact of the EUDR. The products covered by the EUDR represent a mere 8.3 per cent of exports to the EU and 0.7 per cent of all Thai exports, but their value is rising.

Producers and exporters of rubber, wood and palm oil will have to bear substantial costs in adapting to the new regulation; small producers will lose their competitiveness and Thailand risks finding itself excluded from world supply chains.

But if the process is adequately supported, both by the government and through the aid available under the EUDR, Thailand could gain a competitive advantage over its competitors while conserving its forests.

Impact on Switzerland

And what about Switzerland? The country is being indirectly affected by the new provision, as all exports of the seven products to the EU must meet EUDR requirements. Krungsri also states that our country even ranks 17th in terms of impact, with regard to cocoa and especially coffee.

So far, the Swiss government has decided not to adapt Swiss law to the EUDR for as long as mutual recognition with the EU is not possible. This is meant to avoid doubling the administrative burden on Swiss companies. But it plans to conduct an impact study by the summer and to take a decision thereafter.

Civil society is examining the matter. Alliance Sud participates in a working group that is studying whether and how to adapt the EUDR to Switzerland. The concern is to avoid penalising small producers in countries of the Global South. Where necessary, support and training measures should be put in place, and local communities consulted. This would ensure that the fight against climate change does not prejudice the potential for further developing international trade.

Share post now

global

The Alliance Sud magazine analyses and comments on Switzerland's foreign and development policies. "global" is published four times a year (in german and french) and can be subscribed to free of charge.

UN tax convention

Temperatures also rising on the tax policy front in New York

26.07.2024, Finance and tax policy

Next week ushers in another round of negotiations on a Framework Tax Convention at the UN headquarters in New York. Recently, the Swiss Cantons of Basel City and Zug, noted for their low corporate tax rates, again provided new material illustrating why this is an absolute necessity.

Until mid-August, countries from the Global South in particular will be campaigning in New York for a strong UN tax convention - this is likely to make Switzerland and other profiteers of the current tax system sweat. © KEYSTONE / SPUTNIK / Sergey Guneev

Over the next three weeks, the Ad Hoc Committee to Draft Terms of Reference for a United Nations Framework Convention on International Tax Cooperation will be determining the policy scope of the new Framework Convention and also its decision-making procedure. What sounds extremely technical is of great political significance in that, by mid-August, negotiators must determine how much power the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) will hand over to the UN, having dominated the multilateral agenda in international tax policy matters since the 1970s. Should the UN take over the reins in global tax policy in the future, the countries of the North – which continue to dominate economic policy despite the rise of China – would be relinquishing some of their supremacy in this key aspect of tax policy. As might be expected, there is great resistance to a robust UN tax convention from the EU, the USA and the erstwhile beneficiaries of the OECD-led international tax system, i.e., low corporate tax jurisdictions and major financial centres. Both business models benefit from the fact that, despite all the OECD reforms of the past 10 years, corporate profits and assets can still be taxed where rates are lowest or not be taxed at all.

The South in a key position

Negotiating multilateral tax questions in the UN instead of the OECD will alter the majority structure, placing the countries of the South in a key position. The Draft Terms of Reference (ToR) recently released by the Bureau of the Ad Hoc Committee reflects this. The text directly links the tax convention with the funding of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and states the Convention’s aim, among other things, to "Establish an inclusive, fair, transparent, efficient, equitable, and effective international tax system for sustainable development". This aim is to be achieved in the following areas through the corresponding undertakings by signatory countries:

- The fair allocation of taxing rights vis-a-vis multinational enterprises,

- the effective taxation of high-net worth individuals,

- ensuring that tax measures contribute to addressing environmental challenges,

- effective transparency and information sharing for tax purposes,

- the effective prevention and resolution of tax disputes.

Should all these elements be included in the final version of the ToR, all major contemporary problems of international tax policy could in future be addressed in the UN framework: profit-shifting by multinational enterprises to low-tax jurisdictions; high-net worth individuals, who use cunning constructs to evade tax authorities in the global offshore system; the fact that today, taxes are not nearly being sufficiently harnessed as a tool for economic management in the climate policy framework; the lack of transparency in global asset management, and the absence of a level playing field between countries of domicile of multinational enterprises, those that are their markets, and those where their production takes place, when it comes to settling disputes over questions of who may tax which profits of these enterprises, and where. The strong opposition from the Global North is therefore no surprise, even though it is rarely ever made truly explicit.

Unconstructive Switzerland

Switzerland's position on the Draft Terms of Reference is symptomatic of this negotiating tactic adopted by the rich countries, which opt for subterfuge rather than explicitly laying out and defending their own interests. Like most OECD and EU countries, Switzerland favours decision-making by consensus, as the only way to implement, in practice, the multilateral reforms to the international tax system taken up in the Convention. At the same time, Switzerland wishes – again in line with the OECD majority and the EU – to negotiate in the UN framework only topics that have not yet been addressed in the OECD. This excludes corporate taxation, tax transparency, better taxation of high net worth individuals, and new dispute settlement mechanisms. In this connection, Switzerland speaks of a duplication of multinational forums.