Share post now

Article

"The local people always know their needs best"

05.10.2020, International cooperation

Patricia Danzi took over as head of the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) on 1 May, succeeding an FDFA diplomat who had reached the end of his career. In an interview, she lays out some initial priorities.

Patricia Danzi in the interview on September 8, 2020.

© Daniel Rihs / Alliance Sud

Meinung

Persistence pays off

05.10.2020, International cooperation

In 2019, Alliance Sud reported in its magazine “global” on the Swiss agricultural firm GADCO in Ghana. Those in charge rejected the portrayal. Guest author Holy Kofi Ahiabu, the Ghanaian employee of Alliance Suds Kristina Lanz, faced intimidation.

Holy Kofi Ahiabu

Share post now

Article

What does “sustainability” really mean?

09.12.2020, International cooperation

Reflections on an overused concept, the aspirations of which are controversial even in academia. A change of paradigm is needed.

A farmer from the Sikh community works near the Guru Hargobind coal-fired power plant, Punjab, India. Pollutants are repeatedly released into the air and onto the field – which is associated with health problems.

© Chris Stowers / Panos

Share post now

Article, Global

National Contact Point: The limits of dialogue

09.10.2017, Corporate responsibility

Economic associations are opposed to the introduction of civil liability for business-related human rights violations and environmental degradation, as proposed under the Responsible Business Initiative; they point to National Contact Point.

Where people are dwarfed by machines. Photo: At Zambia's Mopani copper mine owned by the Glencore group, some 4,000 tonnes of copper ore are brought to the surface daily. © Meinrad Schade

It should be recalled that governments that have adhered to the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, Switzerland among them, have undertaken to set up a National Contact Point (NCP), which is a non-judicial grievance mechanism whose structure and functioning vary from country to country. The primary function of the NCP is to promote the OECD Guidelines and receive complaints regarding the non-observance of the Guidelines by enterprises.

In Switzerland, the powers and functions of the National Contact Point are laid out in a Federal Council Ordinance, which tasks it, among other things, with “handling specific instances raised regarding presumed breaches of the OECD Guidelines by enterprises and to act as a mediator between the parties”.

An individual or a group may “raise specific instances” with the Swiss NCP, which is empowered, inter alia, to handle issues raised concerning the activities of Swiss enterprises established in non-OECD countries, quite likely in developing countries. Institutionally, the Swiss NCP is attached to the State Secretariat for the Economy (SECO) and has been assisted since 2013 by an Advisory Board composed of 14 members representing the Federal Administration, employers' federations and trade associations, trade unions, NGOs and academia. The NCP Procedural Guidance states that the NCP serves as a “platform for dialogue and mediation” between the parties involved, with a view to helping them resolve the dispute at hand. The NCP may itself conduct the dialogue or seek the assistance of an intermediary or an external mediator. Remarkably, however, “participation in this dialogue is not obligatory”.

Shortcomings and weaknesses of the NCP

The (sole) mission of the NCP is to encourage dialogue between the parties and not that of determining whether the OECD Guidelines have been breached. The NCP may not comment on the possible non-observance of the Guidelines by a multinational enterprise.

In its present form, the Swiss NCP confines itself to providing a platform for dialogue and mediation between the parties to a conflict. Besides, participation in this dialogue is not mandatory and the NCP has no means of persuading or compelling enterprises to take part in it. As such, it is a voluntary mediation procedure that therefore depends on the good will and good faith of enterprises that submit to it. Indeed, mediation is by nature consensual and does no more than offer the parties the chance – but does not require them – to take part in a process of assisted dialogue to settle a dispute.

Regarding the efficiency and efficacy of the Swiss NCP, the main weaknesses in its current structure and functioning are the following:

- Its lack of institutional independence – being attached to SECO – unlike other NCPs that operate as entities independent of the government, one example being that of Norway, which comprises four independent experts;

- stringent confidentiality requirements, or the lack of public access to the procedure;[1]

- the paucity of resources provided to enable the poorest population groups (mainly) in developing countries who are harmed by the activities of multinational enterprises with headquarters in Switzerland to participate fully in the mediation procedure launched by the NCP (specifically to cover the costs of translation and travel for the communities concerned);

- the absence of conclusions in the "final statements" from specific instances regarding the violation of the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and the absence of clear recommendations on measures expected of enterprises to ensure full observance of those Guidelines;

- the absence of a supervisory body (independent body with decision-making power), as the Advisory Board, with its vague mandate, does not fulfil these conditions;

- the lack of material consequences for enterprises in the event of non-participation or bad faith during the proceedings, unlike the case of Canada's NCP which may withhold any commercial support abroad from the companies concerned, or which considers the attitude of enterprises when they wish to access credit/export support.

Complementarity between NCP and access to civil justice

By itself, a platform for dialogue and mediation would not be able to guarantee “Access to remedy” as called for in the third pillar of the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. In fact, these principles affirm that “States should provide (…) non-judicial grievance mechanisms, alongside judicial mechanisms, as part of a comprehensive State-based system for the remedy of business-related human right abuses” (UNGP, 27). The same complementarity is being sought through Recommendation CM/Rec(2016)3 of the Committee of Ministers to Member States of the Council of Europe, whose chapter on civil liability for business-related human rights abuses provides that «Member States should apply such legislative or other measures as may be necessary to ensure that human rights abuses caused by business enterprises within their jurisdiction give rise to civil liability under their respective laws» (§32) and that Member States should consider allowing their domestic courts to exercise jurisdiction over civil claims concerning business-related human rights abuses against subsidiaries, wherever they are based, of business enterprises domiciled within their jurisdiction if such claims are closely connected with civil claims against the latter enterprises (§35).

In this regard, the Federal Council itself recalls, in its National Action Plan for the implementation of the aforementioned UN Guiding Principles adopted in December 2016, the importance of effective national judicial mechanisms in deciding on material consequences and compensation when dealing with business-related human rights violations.

The mechanism for “raising specific instances” provided by the Swiss NCP is no more than a voluntary mediation procedure, as it has no power to rule on the violation of the OECD Guidelines or impose material consequences. It cannot therefore substitute for effective access to legal remedy before a judicial body that is competent to rule on the existence of business-related human rights abuses and impose adequate indemnification as called for under the Responsible Business Initiative.

[1] The NCP procedures remain confidential during the mediation process. The parties involved must also respect this confidentiality and may not make public any information during proceedings (NCP Specific Instance Procedure, paragraph 3.5). Norway, in contrast, allows public access to all information concerning an ongoing procedure, pursuant to the Norwegian Freedom of Information Act.

Share post now

global

The Alliance Sud magazine analyses and comments on Switzerland's foreign and development policies. "global" is published four times a year (in german and french) and can be subscribed to free of charge.

Article

Sustainable Finance: a generational project

06.12.2023, Climate justice, Finance and tax policy

In 2015, governments committed to aligning financial flows with the climate objectives of the Paris Agreement. Where do things stand with implementation? What is Switzerland doing? A stocktake.

The financial sector's commitment to climate protection is very contradictory.

© Adeel Halim / Land Rover Our Panet

Signing the Paris Agreement in 2015 the international community committed to significantly reducing greenhouse gas emissions, aiding developing countries in climate change mitigation and adaptation, and directing both public and private finances into a low-carbon economy and climate-resilient development. Article 2.1(c) of the Paris Agreement embodies this goal. The jargon therefore speaks of "Paris alignment".

On 3 and 4 October, government officials, business leaders and representatives from NGOs came together at the 3rd Building Bridges Summit for a two-day workshop in Geneva to explore this orientation and its alignment with Article 9 of the Paris Agreement. This was done with a view to the first "global stocktake" to be conducted at COP28. Under Article 9, developed countries pledged to extend financial support to developing nations for climate change mitigation and adaptation measures. Numerous delegates and NGOs in Geneva have raised concerns that industrialised countries are emphasising private finance alignment while disregarding their commitment to assisting developing countries.

Financial flows for economic activities based on fossil fuels continue to far surpass those meant for mitigation and adaptation measures. The most recent IPCC synthesis report affirms that sufficient capital exists globally to close the worldwide climate investment gaps. The predicament is therefore not a shortage of capital, but rather the ongoing mismanagement and misallocation of funds that is impacting both public and private capital flows. Nevertheless, redirecting financing and investment towards climate action, primarily in the neediest and most vulnerable nations, is no silver bullet. The challenges of a "just transition" go much further, and developing countries also expect financial support from the North.

Responsibility of governments

Businesses, including those in the financial sector, are not bound by the Paris Agreement. Governments therefore have a responsibility to translate climate change commitments into national legislation. Put simply, "Paris alignment" requires governments to ensure that all financial flows contribute to achieving the climate goals of the Paris Agreement. Implementing Article 2.1(c) will require a variety of instruments, and it is primarily up to individual governments to identify the regulatory frameworks, measures, levers and incentives needed to achieve alignment. This will require concrete steps leading to tangible and measurable results for individual companies and financial institutions.

What is Switzerland doing?

By ratifying the Paris Agreement, Switzerland has also committed to making its financial flows compatible with climate goals. The Federal Council is also working with the industry to ensure that the financial centre plays a leading role with regard to sustainable finance. However, it is still relying primarily on voluntary measures and self-regulation.

With the Climate and Innovation Act, the Swiss electorate decided, in June 2023, that Switzerland should achieve climate neutrality by 2050. Interim greenhouse gas reduction targets have been set, along with precise benchmarks for certain sectors (construction, transport and industry). Broadly speaking, all companies must have reduced their emissions to net zero by 2050 at the latest. With specific reference to the goal of aligning financial flows with climate goals, Article 9 of the Climate Act stipulates that: "The Confederation shall ensure that the Swiss financial centre contributes effectively to low-carbon, climate-resilient development. This includes measures to reduce the climate impact of national and international financial flows. To this end, the Federal Council may conclude agreements with the financial sector aimed at aligning financial flows with climate objectives".

The role and responsibility of Switzerland as a financial centre

The facts are clear: the Swiss financial centre is the country's most important "climate lever". The CO2 emissions associated with Switzerland's financial flows (investments in the form of shares, bonds and loans) are 14 to 18 times greater than the emissions produced in Switzerland! It would therefore be logical for the Federal Council to give priority to these financial flows. Given its size – around CHF 7800 billion in assets under management – the Swiss financial centre could make a significant contribution to achieving the climate goals. However, this would require effective measures here at home to help redirect financial flows. This would include credible CO2 pricing, both domestically and – as yet unimplemented – internationally.

Range of measures for Swiss companies and financial market players

From January 2024, large companies – including banks and insurers – will be required to publish a report on climate matters covering not only the financial risks a company faces from its climate-related activities, but also the impact of its business activities on the climate ("double materiality"). The report must also include companies’ transition plans and, "where possible and appropriate", CO2 emission reduction targets that are comparable to Switzerland's climate targets. Like the UK and a number of other countries, the European Union has introduced similar obligations. Thus, for once, Switzerland is not lagging behind.

PACTA Climate Test

Starting in 2017, the Federal Council has recommended that all financial market players – banks, insurers, pension funds and asset managers – should voluntarily participate in the "PACTA Climate Test" every two years. The aim is to analyse the extent to which their investments are in line with the temperature target set by the Paris Agreement. The test covers the equity and bond portfolios of listed companies and the mortgage portfolios of financial institutions. The PACTA is designed to show the portfolio weight of companies operating in the eight most carbon-intensive industries, which account for more than 75 per cent of global CO2 emissions (oil, gas, electricity, automobiles, cement, aviation and steel).

However, participation in the PACTA test remains voluntary and participants are free to choose the portfolios they wish to submit. Furthermore, the publication of individual test results is not (even) mandatory for financial institutions that have set themselves a net-zero target for 2050. The Federal Council recommends rejecting a motion calling for improvements to these aspects, arguing that existing decisions are already sufficient.

Self-declared net-zero targets

Many Swiss financial institutions have voluntarily set themselves carbon-neutral targets under the auspices of the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ). The Federal Council supports this approach. However, these initiatives raise crucial questions about transparency and credibility. What is the percentage of financial institutions that have set net-zero targets? What is the percentage of assets and business activities that will actually be net zero by 2050? How comparable is the information, i.e., final and interim targets and progress made by financial institutions? To increase the transparency and accountability of financial actors, the Federal Council had originally proposed the conclusion of sectoral agreements with them. This was rejected by the financial lobbies. However, the Climate Act now envisages the conclusion of such agreements, and the Federal Department of Finance is to submit a report on the matter by the end of the year.

Swiss Climate Scores

The Swiss Climate Scores (SCS) were developed by the authorities and industry and introduced by the Federal Council in June 2022 in keeping with GFANZ. The basic idea is to create transparency regarding the Paris alignment of financial flows in order to encourage investment decisions that contribute to achieving the global climate goals. Here too, the approach remains voluntary for financial service providers.

At the Building Bridges Summit, the CEO of the asset management firm BlackRock Switzerland lamented the low uptake of the SCS in her industry. This confirmed the misgivings expressed by Alliance Sud when they were introduced. The daily newspaper NZZ also recently noted the low uptake and inconsistencies in implementation by financial institutions – describing the SCS as a "refrigerator label" for financial products compared to the EU's sophisticated regulatory framework.

Paradigm shift

Implementing Article 2.1(c) of the Paris Agreement will therefore also be a major undertaking for Switzerland. The range of largely voluntary measures adopted so far clearly falls short of the Paris commitments. A paradigm shift is therefore urgently needed.

The Federal Council recently proposed the adoption of a motion calling for the creation of a "co-regulation mechanism" and a commitment that this mechanism would become binding "if, by 2028, less than 80 per cent of the financial flows of Swiss institutions are on track to achieve the greenhouse gas reductions envisaged in the Paris Agreement".

It is now up to the parliament to take the first steps to tackle this generational project.

Share post now

Article, Global

Blended Finance: Dream or reality?

10.12.2020, Financing for development

The 2030 Agenda rests on what is hitherto the most ambitious funding strategy for sustainable development. Is it realistic to think it possible to raise trillions for the sustainable development goals?

A worker controls beer production in Beni, Democratic Republic of Congo. It is questionable whether private investors also have poverty reduction in mind. © Kris Pannecoucke / Panos

In addition to public funds, private funding sources – domestic and foreign – are deemed indispensable. This is even viewed in some circles as the ideal way of meeting the funding shortfalls. More specifically, these private funds encompass private investments as well as philanthropy and remittances.[1] In its International Cooperation Strategy 2021-2024, the Swiss Government advocates for diversifying and scaling up cooperation with the private sector; it envisages deploying Official Development Assistance (ODA) funds as a means of raising "additional private funds" for sustainable development.

The Blended Finance approach in particular is one of the financial vehicles intended to attract private resources for sustainable development financing. While it has generated very high expectations, the outcomes to date have been rather modest.

Let us try to achieve some clarity on the basis of five questions:

1. Blended Finance: What is it about?

There is no universally accepted definition of Blended Finance. The underlying idea, however, is for funds and other resources (personnel, expertise, political contacts, etc.) from bilateral and multilateral official development aid to be deployed as a "levers" to mobilise private sector investments for development cooperation.

2. What are the currently existing models?

In practice, Blended Finance works as follows: private investors generally aim for a financial return commensurate with the investment risk, in other words, a risk-adjusted return. The higher the risk – real or perceived – the higher must be the hoped-for return to offset that risk.

In public financing (bilateral or multilateral), there are essentially two approaches to attracting private investors to projects that (a priori) do not meet risk-based return expectations. Under one approach, the investment risk to the private investor can be reduced (de-risking); under the other, the potentially yield accruing to the private investor can be increased.

In general, risk reduction through instruments such as guarantees or first loss capital is applied to projects that seem profitable enough but carry a considerable risk of default or loss of value. The yield may be increased by granting preferential loans to the investor to offset certain project costs, or through an equity stake. These are ways of offering an investment incentive to private investors. Another possibility is technical assistance to reduce certain transaction costs (in the form of feasibility studies, for example).

Both approaches – reducing risk and increasing return – are tantamount to subsidising private investors from official development assistance funds.

3. How does this benefit the poorest?

This is the key question. The Federal Act on International Development Cooperation states that such cooperation is meant to support "primarily the poorer developing countries, regions and population groups" (Article 5.2). To this day, however, there is little evidence of any benefit from such blended finance in the poorest countries.

Blended Finance has indeed grown exponentially, but has so far bypassed the least developed countries (LDCs). The bulk of Blended Finance transactions have gone to middle income countries (MICs), where the main beneficiaries are the sectors with the highest return on investment – i.e. energy, financial services, industry, mining and construction. Sectors like education or health are hardly involved.

4. What are the risks?

Blended Finance carries the following risks:

- First, it must be borne in mind that if the volume of international cooperation funding remains constant, increased support for this form of financing means a decline in "classic" official development assistance (ODA) funds.

- Second, development funding intended for LDCs could come under pressure if blended finance projects take place principally in MICs.

- Third, there is a danger that the internationally recognised principles of the effectiveness of development cooperation may not be respected; these principles specifically require that development priorities are set inclusively, in other words, in agreement with the beneficiaries.

- Fourth, the use of such funding instruments could cause market distortions in developing countries and crowd out local enterprises and investors.

- Lastly, blended finance entails a debt risk for developing countries.

The Alliance Sud Position paper "Blended Finance – Mischfinanzierungen und Entwicklungszusammenarbeit" (in German and French) offers an in-depth analysis of the potential, limits and risks of blended finance and makes some recommendations.

5. What are the alternatives?

The question generally arises as to whether and under what circumstances the use of Blended Finance and partnerships between players from official development cooperation and private enterprises could fulfil the (high) expectations placed on them.

It should be recalled in this connection that the Addis Ababa Action Agenda (AAAA) provides for the mobilisation of domestic public resources as a priority area of intervention for development financing and that combating illicit financial flows is indispensable in this context. Moreover, in developing the private sector, priority should go to local enterprises, especially micro, small and medium-size enterprises (MSMEs) – especially businesses run by women – and to domestic financial markets.

Blended Finance can thus be just one among several financial instruments with which to implement the 2030 Agenda.

[1] Over recent years, remittances – money sent back to their home countries by workers living and working abroad – have skyrocketed. For numerous developing countries, they currently represent the most substantial source of foreign financing, outstripping even Official Development Assistance (ODA) and Foreign Direct Investment (FDI).

Blended Finance: negligible impacts on poverty

A mere 6 per cent of the USD 157 billion in private funding raised between 2012 and 2017 – or USD 9.4 billion – went to least developed countries (LDCs). Furthermore, Blended Finance projects in LDCs tend to attract less private funding.

Some 55.5 per cent of these funds go to the energy and banking sectors, while just 5.6 per cent go to projects in the social sectors.

The modest level of Blended Finance activities in LDCs underscores the fact that like private financing, this form of mixed funding falls on fertile ground in those regions with the smallest obstacles to the mobilisation of capital.

Blended Finance projects have often succeeded in mobilising additional funds, but these have generally had little impact on poverty. It is more often the case that owing to inadequate monitoring and reporting as well as to a lack of transparency, the development impact is not known. All Blended Finance endeavours ought to be based on co-determination by the respective countries. Projects that are guided by the priorities of developing countries and take local and national players on board are more likely to achieve sustainable outcomes.

Source: Financing for Sustainable Development Report 2020. Inter-agency Task Force on Financing for Development.

Share post now

global

The Alliance Sud magazine analyses and comments on Switzerland's foreign and development policies. "global" is published four times a year (in german and french) and can be subscribed to free of charge.

Article

«A prosperous Africa is in our interest»

11.02.2021, International cooperation

During Swiss Federal Councillor Ignazio Cassis' official visit to North and West Africa from 7 to 13 February 2021, the priorities of the new MENA and Sub-Saharan Africa 2021-2024 strategies were at the heart of the discussions.

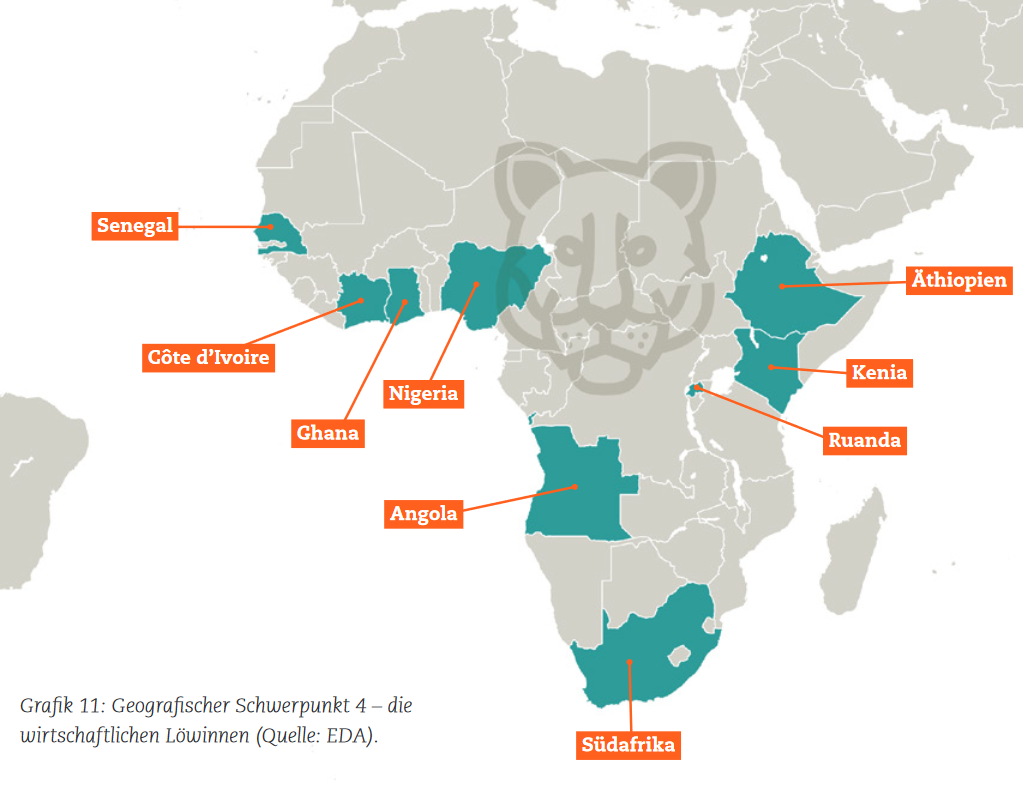

"The lion economies"

© FDFA

According to the Swiss Minister of Foreign Affairs, it would be wrong to limit Switzerland's role to conflict mediation or humanitarian aid; it would also be desirable to create opportunities for Swiss companies and to strengthen public-private partnerships. Interview with our Business and Development expert Laurent Matile to illustrate Alliance Sud's position.

In its first strategy for sub-Saharan Africa, the Swiss Government's stated aim is also to serve Switzerland's interests, including economic interests and those of its enterprises. Is this acceptable in your opinion?

What is in the interest of Switzerland (and of the members of the international community) is to contribute to a stable Africa, living in peace, a prosperous Africa, which can offer future prospects for its young people, women and minorities, in terms of decent jobs, and which allows greater participation in political, economic and social decision-making, also for disadvantaged populations.

We therefore welcome the fact that Swiss international cooperation is primarily aimed at supporting peace, security and the promotion of human rights, and that Switzerland remains committed to democracy and the rule of law and supports civil society initiatives in these areas.

These objectives also serve the interests of Swiss enterprises wishing to invest in these countries or to export products or services to them. A stable economic environment, where the rule of law and the protection of human rights are guaranteed, is a prerequisite for sustainable economic development and prosperity.

Shouldn't the focus instead be solely on strengthening local economies?

It is not a question of having a binary vision; above all, Switzerland's policies for sustainable development, including its foreign economic policy, must be coherent. We consider that the promotion of local enterprises in the African partner countries must remain a priority of Switzerland's international cooperation (IC). Supporting local entrepreneurship, SMEs - as the backbone of any economy - with a special focus on quality education for young people and their vocational training is an important tool in the fight against unemployment. Not forgetting support for equal access to the labour market for women and minorities.

What is the role of the Swiss private sector in strengthening local economies? Is a commitment desirable and if so, under what conditions?

What shall be expected from Swiss companies is that they guarantee "responsible business conduct", i.e. that they adhere to and implement the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and the UN Guidelines on Business and Human Rights; specifically they should:

- respect human rights ;

- do not cause damage to the environment ;

- create decent jobs;

- make an equitable tax contribution, including ending aggressive practices of profit shifting to tax havens;

- do not engage in corrupt practices.

Beyond this, companies must invest over the long term (i.e. avoid purely speculative and/or short-term investments) and help establish linkages (upstream and downstream) with local businesses, to provide business opportunities for the local private sector and thus contribute to the diversification of the economic fabric of African countries.

Beyond contacts with State and business representatives, it would be desirable for Federal Council Cassis to talk to representatives of trade unions and civil society to find out their position and requests concerning the contribution of Swiss companies to the economic development of the countries in which Swiss International Cooperation is active.

Share post now

Investigation

New electric buses in Bangkok – no substitute for climate protection in Switzerland

11.12.2023, Climate justice

Switzerland is celebrating the world's first carbon offset programme under the Paris Agreement that will help the country fulfil its own climate goals. Emissions are being reduced in Bangkok through the co-funding of electric buses. A detailed study by Alliance Sud and Fastenaktion reveals that the investment in electric buses in Bangkok would have taken place by 2030 even without an offset programme.

Bangkok, Rachadamri road, 11th October 2022.

© KEYSTONE / Markus A. Jegerlehner

Under the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, industrialised countries were already able to offset greenhouse gas emissions through projects in the Global South. The Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) was developed for that purpose. The voluntary offset market developed in the wake of the CDM, for example, allowing companies to promote "carbon neutral" products without actually reducing their emissions to zero. Both mechanisms, the CDM and the voluntary mechanism, have repeatedly attracted criticism. Studies and research papers show that many of the associated climate projects eventually turn out to be largely useless, and in some cases, harmful to local communities.

The Paris Agreement, which succeeded the Kyoto Protocol, redefined the carbon market and made a distinction between an intergovernmental mechanism (Article 6.2) and a multilateral mechanism (Article 6.4). Under the Agreement, all countries are required to pursue the most ambitious possible climate policy. Article 6 provides that the aim of both mechanisms is to allow for higher ambitions through such cooperation. In other words, carbon emissions trading should enable countries to lower their emissions more quickly. In the negotiations, Switzerland did much to promote this bilateral trade in certificates, and is now leading the way in operationalising it. Switzerland has already signed a bilateral agreement with 11 partner countries, and another three agreements are expected to be concluded at COP28 in Dubai.

Art. 6 of the Paris Agreement

1. Parties recognize that some Parties choose to pursue voluntary cooperation in the implementation of the nationally determined contributions to allow for higher ambition in their mitigation and adaptation actions and to promote sustainable development and environmental integrity.

[...]

Domestically, the Swiss government and the centre-right parliamentary majority interpret this possibility as carte blanche not to pursue the country's stated goal of a 50 per cent reduction in emissions by 2030, within Switzerland. In other words, the possibility to buy certificates is not being used to reach higher goals. This is eminently clear from the current review of the CO2 Act, as it provides for remarkably limited emission reductions in Switzerland for the 2025–2030 period. Compared to 1990, the rollover of the measures currently in place is expected to yield a 29 per cent reduction by 2030. Under the government's proposal, the new CO2 Act is expected to produce a mere five percentage point reduction, i.e., -34% vis-à-vis 1990. However, if Switzerland is still to achieve its 50 per cent reduction target on paper, it will have to purchase more than two-thirds of the additional reduction needed (15 per cent of 1990 emissions) in the form of certificates from partner countries. The partner countries must forego including those emission reductions in their greenhouse gas balance. As the first chamber, the Council of States proceeded to further water down the government's already weak domestic ambitions in the CO2 Act, i.e., to a less than four percentage point reduction in five years. In so doing it has intensified the pressure, in the short time remaining until 2030, to produce sufficient certificates in partner countries, and this to very exacting qualitative requirements. That this is no simple matter is borne out, not least of all, by the problems mentioned initially, which have already come to light in the CDM and the voluntary carbon market.

Switzerland has approved three offset programmes since November 2022. Two were developed by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). The first is intended to reduce the output of methane from rice farming in Ghana, and the second, to promote the use of decentralised mini-solar panels on outlying islands in Vanuatu. Both programmes are intended to serve the federal administration's voluntary carbon offsetting endeavours.

The third programme approved – the Bangkok E-Bus Programme – is the world's first, under the Paris Agreement, in which emission reductions are to count towards the reduction goals of another country, namely Switzerland. The programme was commissioned by the KliK Foundation and is being implemented by South Pole, in partnership with the Thai company Energy Absolute – which is 25 per cent owned by UBS Singapore. Its purpose is the electrification of publicly licensed buses in Bangkok, which are operated by the private company Thai Smile Bus. The additional funding derived from the sale of certificates to the KliK Foundation in Switzerland is intended to cover the price difference between traditional and electric buses, as investing in new electric buses is not financially viable for private investors and would therefore not happen. Replacing old buses and operating some new bus lines is expected to save a total of 500,000 tonnes of CO2 between 2022 and 2030. The new buses began operating in autumn 2022.

Alliance Sud and Fastenaktion have studied the publicly available documents on the Bangkok E-Bus Programme and identified shortcomings in the additionality aspect, and in the quality of the information provided. They heighten concerns that the purchase of offset certificates is no equivalent substitute for domestic emission reductions. The certificate trading approach is fundamentally at odds with the principle of climate justice, whereby the countries mainly responsible must cut their emissions as quickly as possible.

KliK

The Foundation for Climate Protection and Carbon Offset KliK is owned by Switzerland’s fuel importers. The CO2 Act requires these companies, at the end of each year, to surrender offset certificates to the federal government, whether from Switzerland or abroad, covering some part of their fuel emissions. To that end, KliK develops programmes with partners through which it can purchase certificates

Shortcomings regarding additionality

One key condition for a one-tonne CO2 reduction elsewhere to become an equivalent substitute for one's own reduction is that of additionality. This means that without the additional funding from emission certificates, the emission-reducing activity such as replacing diesel-driven buses with electric ones, would not have taken place. This condition is crucial if a climate benefit is to exist. It is also enshrined in the CO2 Act. This is because a traded tonne of CO2 legitimises a further tonne of CO2 emissions by the purchaser, which is then shown on paper as a reduction.

Those in charge of the Bangkok E-Bus Programme must therefore prove that without the programme, the public bus lines run by private operators like Thai Smile Bus would not be using electric buses before 2030. Various factors must be considered in the process: For one thing, this electrification must not have been part of an already planned government subsidy programme, and for another, this investment may not be undertaken by private parties anyway.

Subsidy programme: The official programme documentation barely explains the government's failure to subsidise the introduction of e-buses to replace the old buses, which also contribute substantially to local air pollution. According to the programme documentation, promoting electromobility and energy efficiency in the transport industry in general is part and parcel of government plans. But subsidies were granted only to public bus operators, not to private ones, in other words, not to the programme's target group. The document does not explain why government subsidies are available only for public operators. Besides, no mention is made of Thai subsidies (mainly tax advantages) for private investors engaged in the manufacture of batteries and E-buses, for instance, and of which Energy Absolute is also a beneficiary.

Investment decision: For additionality to exist, the project owner must demonstrate that no positive investment decision could have been possible without the emissions-related funding. To that end, the programme documentation contains a calculation which is meant to prove that without the additional funding from the sale of certificates, the private investment would not have been profitable and hence would not have taken place. The sales proceeds are expected to cover the cost difference between the new purchase of traditional buses and the new purchase of e-buses, calculated for their entire service life. However, neither the price difference nor the way it was calculated is mentioned in the official documents. When contacted, KliK furnished no detailed information, stating that this was "part of the contract negotiated for financial support of the E-Bus Programme", in other words, a private matter between KliK and Energy Absolute. It is therefore not possible to examine the key argument as to why the funding programme is needed for the e-buses. Consequently, additionality is at best non-transparent, and at worst, non-existent. But the price difference argument is also remarkable, in that as an investment firm, Energy Absolute specialises in green technologies. As such, the firm would hardly have decided to invest in the purchase of buses with combustion engines. On the other hand, it is plausible that a major investment in e-buses would have taken place in the next few years anyway, because, even before the 2022 launch start of the programme, Thai Smile Bus had been operating e-buses on the streets of Bangkok, a fact borne out by several media and a Twitter post with pictures (see Figure below). Hence, there must have been funding pathways for e-buses prior to the Bangkok E-Bus Programme. This clearly contradicts the assertion that e-buses would not have been introduced in Bangkok without the offset programme. At a minimum, the programme documentation should have laid out this problem in detail and explained why, despite this, the programme is deemed to entail additionality.

Lack of transparency and poor quality of the publicly available information

Once a programme is approved by both participating States, the Swiss Federal Office for the Environment (FOEN) publishes the programme documentation. It explains and lays out the methods used to calculate the expected emission reductions and also how additionality is to be ensured. The programme rationale is also explained, and other aspects such as the positive implications for the UN sustainable development goals are also addressed. This is intended to make the programme comprehensible to outsiders. A test report by an independent consulting firm is also made available, confirming the information given in the programme documentation. On the basis of these documents, FOEN and the Thai authorities verify, then approve the programme. Switzerland's approval is also made public.

The Bangkok E-bus Programme lacks transparency around key aspects. First, the programme documents refer to an Excel document in which the expected emission reductions are calculated – but the document containing the calculation is not made public. Alliance Sud requested and obtained it, and sees no reason why it should not be published. Second, key aspects such as the cost of the certificates and the scale of the requisite funding are negotiated in the private contract between Energy Absolute and the KliK Foundation. KliK writes the following in that regard: "The commercial aspects are confidential." The contractual conditions between the programme owner Energy Absolute and the bus operator Thai Smile Bus also remain private. This gives rise to the aforementioned lack of transparency around additionality. Even the FOEN, which must verify the additionality aspect of the programme, is unable to access the information in the private contract for that purpose. Responding to an enquiry from Alliance Sud, the FOEN confirms that the contracts are not part of the project documentation.

Qualitative shortcomings can also be detected in the information published via the programme documentation. The following are some examples:

● The roles and responsibilities of the players involved remain somewhat unclear. The investment is being made by Energy Absolute, although it is Thai Smile Bus that needs the vehicles. There is no mention of the fact that the Energy Absolute group of companies not only produces renewable energy, batteries and charging stations, but also holds a stake in the e-bus manufacturing company – and, as gleaned from internet searches, acquired a stake in the Thai Smile Bus company concurrently with the launch of the programme. The long-term benefits of such an investment for the financially successful Energy Absolute group are not discussed.

● There is contradictory information regarding the scale of the programme. The programme documentation speaks of a maximum reduction of 500,000 tonnes of CO2, for which at least 122 bus lines are being electrified (at least 1900 buses). A few pages on, however, it is stated that funding through the certificates is needed for the first 154 e-buses, which will ply eight routes and account for a fraction of the anticipated CO2 emission reductions. Besides, the investment return is calculated for just 154 e-buses. When contacted, however, KliK writes that the certificate price will cover the funding gap for all e-buses under the programme, not just the first 154.

● Promises are made that are hard to keep. For example, the PM 2.5 air quality level is to be monitored in order to gauge the reduction in the air pollution caused by the old buses. The positive, non-polluting nature of e-buses is rightly mentioned, but even if air pollution were to diminish measurably, it would be extremely challenging to establish a causal link to the activities of this programme. The programme document outlines no such procedure.

● The programme's "pioneering achievement" is being exaggerated, for example, through assertions that “it introduces new technology to the Thai public” – although the same company had previously been operating e-buses on the streets of Bangkok. The Klik website even contains manifestly false statements: "Thailand is currently not using electric buses on scheduled routes as a means of public transport. This is the result of a lacking infrastructure and manufacturing capacity of e-buses & batteries. This programme is therefore to be seen as a first-of-its kind undertaking to push Thailand on its EV journey towards a decarbonised economy."

Busstop at Rachadamri road in Bangkok.

© KEYSTONE/Markus A. Jegerlehner

Conclusion: Offset certificates are no substitute for emission reductions at home

The switch to e-buses in Bangkok is a significant and good thing in itself. Switzerland, however, is a striking example of the failure to use the partnership mechanism under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement for the purposes of higher ambitions and greater climate protection. Switzerland's aim, by 2030, to cut its emissions by 50 per cent from their 1990 levels, is less ambitious than that of the EU (-55%) which, rather than rely on offsets abroad, negotiates political reforms to facilitate rapid decarbonisation in Europe. Following the defeat in the referendum on the CO2 Act in 2021 in Switzerland, the government and the parliamentary majority were all too willing to give up the pursuit of any ambitions within Switzerland. The strong reliance on carbon offsetting is not a reflection of technical challenges in implementing Switzerland's climate policy. On the contrary, Switzerland is delaying possible domestic measures, so that even faster reductions will later become necessary. Offsetting abroad is a political decision taken by the centre-right majority in the government and parliament, even though many additional measures in Switzerland would have been approved by a majority of the electorate. The market mechanism in Article 6 can jeopardise the achievement of the Paris climate goals, as it is the easiest way for a rich country to meet its goals on paper. This therefore makes a mockery of the true purpose of the Paris market mechanisms, that of helping to raise climate ambitions.

From the standpoint of climate justice, this pathway is all the more disturbing, considering that the climate crisis is hitting the world's most vulnerable people the hardest. Switzerland owes it to these people and to future generations to lower greenhouse gas emissions as quickly as possible. The International Panel on Climate Change has underscored that the world must achieve net zero emissions by the middle of the century if the Paris climate goals are to be met. There is no place in a net-zero world for substantial trading in emission reduction certificates. The Swiss policy of purchasing such certificates is therefore unnecessarily and unfairly delaying action that is urgently needed here in Switzerland. This injustice is deplored also by civil society organisations in countries in the Global South.

Lastly, like similar journalistic research on other programmes, this study also shows that offset schemes can offer no real assurance of additional emission reductions. At no level is the purchase of certificates an equal substitute for emission reductions at home.

Share post now

Article, Global

Private sector engagement: a perilous path

22.03.2021, International cooperation, Financing for development

In implementing the International Cooperation Strategy 2021-2024, the SDC plans to scale up its cooperation with the private sector and strike up new partnerships. How is this impacting developing countries?

Foreign Minister Ignazio Cassis visits a tourism education institute during his trip to Africa in February 2021.

© Foto: YEP Gambia

Working with the private sector is nothing new in the framework of Switzerland’s international cooperation, whether in the activities of the State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (SECO) or the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC).[1] In accordance with Sustainable Development Goal No. 17 enshrined in the 2030 Agenda, that of entering into partnerships in pursuit of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), Swiss international cooperation had already increased involvement with the private sector during the period 2017-2020.[2] So far, however, that cooperation had never been framed within an SDC strategy. This will now change, at least in part.

Published in January 2021, the “General Guidance on the Private Sector in the context of the International Cooperation Strategy 2021–24” lays out the basic principles governing SDC activities in connection with the private sector and outlines various forms of cooperation with private sector players, as well as the associated challenges and opportunities.

Considering that the private sector makes “the largest contribution to global poverty reduction and sustainable development” – especially as pertains to jobs, taxes and “innovative products that increase living standards in developing countries”[3] – the document states that the Federal Department of Foreign Affairs (FDFA) as well as the Federal Department of Economic Affairs, Education and Research (EAER) plan to step up cooperation with the private sector under the International Cooperation Strategy 2021-2024 and the Federal Council’s new 2030 Sustainable Development Strategy.

In this connection, the SDC points out that in addition to official development assistance (ODA) and domestic tax revenues, the 17 Sustainable Development Goals can only be achieved if “private sector investments are successfully mobilised.” The private sector is therefore considered by SDC as “part of the solution” for reaching the global development and climate protection goals.

Four areas of activity

For the SDC, private sector involvement in sustainable development is focused on the following four areas of activity: (1) Economic policy frameworks: this includes promoting the rule of law as well as responsible business conduct and sustainable investment. (2) Promotion of local companies in the priority countries for Swiss international cooperation, especially small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). (3) Private Sector Engagement (PSE): this entails engaging in partnerships with private sector players from Switzerland and other countries. And last but not least, (4) Public procurement. This area of activity encompasses SDC contracts awarded to private sector players (at home and abroad), which must meet more stringent sustainable development criteria in the future.

PSE – did you say PSE?

According to the SDC, the third area of activity, private sector engagement (PSE) encompasses ways in which Swiss international cooperation can engage with “established" private sector players that “consistently promote” sustainable development. The SDC states that such private sector players – in both the real economy and the financial sector – can contribute to poverty reduction and therefore make interesting partners for international cooperation. They include large companies and multinational enterprises, SMEs, social enterprises, impact investors and grant-making foundations. Each of these categories has its own “specific strengths”. In this connection, the SDC also mentions, for example, NGOs and academic institutions as possible implementation partners.

As stated in the “SDC Handbook on Private Sector Engagement”, the SDC plans, over the medium term, in other words during the implementation of the International Cooperation Strategy 2021-2024, to increase engagement with the private sector as well as the financial volume of its PSE portfolio. In addition to “traditional” PSE approaches, “new financial instruments” are to be developed, whereby the volume of public-private cooperation can be increased also in least developed countries (LDCs) and in fragile contexts.

500 million per year?

Although the document mentions that the setting of a quantitative growth objective is not meaningful, it does note that currently some 8 per cent of all SDC-funded projects (bilateral activities and global programmes) entail partnerships with the private sector. Based on a combination of various factors, it is estimated that over the long run, some 20-25% of all SDC operations could be implemented in collaboration with the private sector, in both the bilateral and multilateral spheres. If we take as a baseline value the 2020 volume of spending of CHF 165 million for the roughly 125 existing partnerships, the volume could rise to almost half a billion in annual spending over the long term.

It should be recalled that the International Cooperation Strategy 2021-2024 makes no provision for the increase of the respective credit lines for the funding of these partnerships, but provides for them to be paid for with funds already earmarked for bilateral development cooperation.[4] This means that the increase in partnerships with the private sector will take place at the expense of other forms of cooperation that have been shown to hold implications for poverty alleviation, more particularly programmes in support of essential public services including education and health. It could also negatively impact other forms of private sector support in developing countries, including the promotion of local SMEs.

What are the impacts?

It is therefore necessary to ensure the developmental impacts of these partnerships and the relevance of the goals being pursued through this kind of cooperation with the private sector. On this point, the “General Guidance on the Private Sector” nevertheless remains vague, or as it stands, fails to convey any clear idea of how SDC plans to guarantee, under such partnerships, the effective fulfilment of its primary mandate, that of combating poverty in priority countries.

The SDC internal handbook lays out various criteria and modalities for cooperation as well as a complex risk analysis procedure. But as always, the devil is in the detail. The SDC will have to ensure that in creating the partnerships, these criteria and processes are effectively observed by all players and not merely ticked off on a list.

Given the clear trend among the Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) and bilateral donors, the SDC could find itself under pressure to “boost” its PSE portfolio without being able to guarantee that these partnerships are consistent with the core objective of the 2030 Agenda, that of “leaving no one behind”.

[1] See external audit report 2005-2014 on the promotion of employment.

[2] See “Switzerland’s international cooperation is working. Final report on the implementation of the Dispatch 2017–20”, p. 7.

[3] This statement must be qualified in many respects. More on this later.

[4] “In the event that the SDC establishes new forms of cooperation with the private sector, a new budgetary credit line could be created and the requisite funding will be drawn from the ‘Development cooperation (bilateral)’ credit.” IC Strategy 2021-2024, p. 35.

Share post now

global

The Alliance Sud magazine analyses and comments on Switzerland's foreign and development policies. "global" is published four times a year (in german and french) and can be subscribed to free of charge.

Article, Global

UNGPs: a decade of incoherent action

16.02.2021,

Business-related human rights violations are frequent occurrences. Yet there is an international framework designed to provide solutions. This month marks the 10th anniversary of the adoption of the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights.

© Nic Bothma / EPA

Major international brands are implicated in forced labour at factories associated with Uighur internment camps in Xinjiang; there are commercial links between Western companies and the conglomerates controlled by the military junta in Myanmar. Corporate accountability is currently a hot-button issue, both in Switzerland and beyond.

Under its mandate to promote the UNGPs, the United Nations Working Group on Business and Human Rights has initiated a project to design the path for a new "decade of action" (UNGPs 10+). The aims are to take stock of accomplishments to date, assess existing gaps and challenges and, above all, formulate a vision and a roadmap for the broader and more extensive implementation of the UNGPs by 2030. The project is supported notably by the German Government and by the Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs (FDFA).

In the words of Anita Ramasastry, Chairperson of the aforementioned Working Group, “this 10-year anniversary must represent a real inflection point for the future we want. We are facing climate and environmental crises combined with other major global challenges such as shrinking civic space, populism, corruption, conflicts and fragility, as well as the still unknown human consequences of technological disruption”. The social and economic crisis spawned by Covid 19 has laid bare and amplified gross existing inequalities and structural discrimination. The 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) emphasise that responsible businesses are a part of the solution. The three pillars of the UNGPs lay out what is needed in practice: States must protect human rights, companies have a responsibility to respect human rights and victims must have access to effective remedy.

The UNGPs have so far helped to bring about substantial progress, but much more remains to be done in order to achieve their own vision of "tangible results for affected individuals and communities, thereby also contributing to a socially sustainable globalisation."

On the positive side, the UNGPs provide a globally agreed standard and baseline for what governments and businesses need to do to embed respect for human rights in a business context – something which did not exist before 2011. One of the most telling examples is the key UNGPs concept of corporate human rights due diligence. It is now at the centre of regulatory developments in Europe, with increasing backing from business and investors.

At the same time, prevention remains inconsistent, relatively few governments are taking action beyond lip service to the UNGPs, and access to remedy for business-related harms is a major and urgent challenge

Challenges and gaps of the UNGPs: viewpoints from Africa

Among the gaps and key challenges underlined by the African Coalition for Corporate Accountability (ACCA) in its submission to the Working Group is the on-binding character of the UNGPs: "The fact that no specific legal consequences are attached to the violation of UNGPs, especially for companies, is undoubtedly one reason for their failure to be effective in Africa.”

Another major challenge is the inadequacy of the existing legal framework, in particular as regards land ownership rights. Most commercial activities in Africa in fact require and depend on the acquisition of large areas of land to the detriment of local communities. The way land is held presents an array of obstacles for communities seeking access to remedy when land is taken or harmed due to international investment and development projects.

According to the ACCA, the third major challenge is the failure of the third pillar concerning access to remedy. In Africa, the communities and individuals whose rights are affected by business-related activities have faced major challenges in accessing timely and effective remedies. There is "a wide range of options for remedies but not enough actual remedy." Moreover, the power of enterprises and the absence of the rule of law represent an enormous challenge. There is an increasing corporate capture of state institutions that has led to corporate impunity in Africa. There is shrinking space for most human rights defenders on the continent to operate. Speaking up about human rights and environmental abuses from business activities in Africa is more dangerous.

It is therefore critical that extraterritorial obligations of States over transnational corporations be strengthened in policy and legal frameworks to ensure effective access to remedy measures beyond national remedial mechanisms. In other words, countries that are host to the corporate head offices and/or decision-making centres of enterprises should adopt binding legislation designed to avert human rights abuses and ensure access to remedy.

Ten years of procrastination by Switzerland

It is interesting to read in Switzerland's submission of January 2021 to the UNGP 10+ project that the medium and long term objective should be to achieve balanced international regulations; the submission further states that this could take the form of an international reference framework based on the Guiding Principles of both the UN and the OECD, as well as the OECD Guidelines on Due Diligence, on which basis each State could develop a suitable national legal framework relating to the observance of human rights by enterprises. The convoluted language is striking. But let us move on from words to deeds!

It is recalled, besides, that in late 2016 the Federal Council had adopted only a national action plan relating to business and human rights, and it was hardly consistent with the Federal Council’s position and action plan on corporate responsibility towards society and the environment, dated April 2015. Sharply criticised by the NGOs as “lacking action and ambition", these two documents were revised in January 2020 and now cover the period 2020-2023. Moreover, the Federal Council had initially opposed the Responsible Business Initiative without putting forward a counterproposal; it then changed its mind and in a tactical move submitted a hybrid text to Parliament after all, one that did no more than incorporate elements of legislation already in force in the EU and the Netherlands in order to sow confusion in the minds of the public in connection with the vote of 29 November last. Alliance Sud will be closely monitoring the implementation of the watered-down counterproposal – set to take effect in January 2022 – and will continue to advocate that Switzerland should adopt substantive and binding legislation in order to ensure full respect for human rights and the environment by business, as well as access to remedy.

Share post now

global

The Alliance Sud magazine analyses and comments on Switzerland's foreign and development policies. "global" is published four times a year (in german and french) and can be subscribed to free of charge.