Share post now

global

The Alliance Sud magazine analyses and comments on Switzerland's foreign and development policies. "global" is published four times a year (in german and french) and can be subscribed to free of charge.

UN Financing for Development Conference

26.09.2025, Financing for development

Attendees at the fourth UN Financing for Development Conference (FfD4) in Seville were in no doubt that more money had to be procured from where it is available, namely, from companies and high net worth individuals. Opinions nevertheless diverged considrably as to the "how".

Voicing opposition to debt burdens and shrinking space: civil society protest at the FfD4 conference building in Seville. © Jochen Wolf / Alliance Sud

The FfD4 conference in early July took place in one of the most problematic phases for global development in decades. Official development finance seems set to dwindle by 17 per cent in the year 2025 alone. On top of that, the fate of USAID – once the world's biggest donor – was definitively sealed during the very conference itself. With less than five years remaining to the deadline, there is still an annual funding gap of more than 4 billion US dollars for meeting the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

It is not as though there were a basic lack of funds – since the last FfD conference in Addis Ababa in 2015, the wealthiest one per cent of the world's population has increased its wealth by more than 33.9 trillion dollars, i.e., 22 times the amount that it would take annually to eliminate absolute poverty. According to the UN Organisation for Trade and Development (UNCTAD), Africa alone could raise almost 89 billion dollars annually if illicit financial flows were stopped. One half of that amount is down to tax avoidance by corporations, and the commodities sector is far and away the leading source of such financial flows. Switzerland ought really to be taking an interest in this.

The conference's non-binding final document, the "Compromiso de Sevilla" had already been approved almost unanimously on 17 June in New York. Hence, no further negotiations took place in Seville. The USA had been very instrumental in watering down the text with respect to climate, for example. Yet that country withdrew from the process two weeks before the conference, becoming the only country not to support the final document. Furthermore, the USA stayed away from Seville.

Despite this, there were more than 15,000 attendees at the conference, including 60 Heads of State and Government, 80 ministers, UN Secretary-General António Guterres, and high-level representatives from UN agencies and other international organisations. For its part, Switzerland opted not to send a high-level delegation. The lack of ministerial status meant that in the official part of the conference, Switzerland could only take the floor at the very end. And because no Federal Councillor bothered to attend, Switzerland missed out on dialogue with the 60 Heads of State and Government in attendance. The road to Seville is simply longer than to Davos, and besides, it was much too hot there.

Because the Financing-for-Development process encompasses much more than "development finance" as understood in the context of international cooperation, several Federal Councillors could well have attended. Action to combat tax avoidance and illicit financial flows was just as high on the agenda as the topics of debt and debt relief, trade and development, or systemic issues of the international financial architecture.

One topic dominated the agenda, namely, "Mobilising Private Resources", which was about the incentives that could be deployed to persuade profit-oriented companies and investors to fill the gap left by the shortfall in government funds. Empty clichés were deployed, such as "Accelerating the Shift and Private Climate Investment at Scale", "Catalytic Pathways to Scale Private Investment", "Unlocking Ecosystems for Inclusive Private Sector Growth", "Impact Investing, from Pioneering Innovations to Scalable Solutions", and so on and so forth.

One might think that this was because "business representatives" made up 40 per cent of attendees, and they were holding a "Business Forum" of their own. In the official sessions, however, the topic was just as dominant among governments (especially those from the North) and international organisations. The same was true for Switzerland. Most of the events it organised revolved around the topic (e.g., "Accelerating SDG Impact through Outcomes-based Financing").

Private sector strengthened, mission accomplished? Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez with UN Secretary-General António Guterres and European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen. © Bianca Otero / ZUMA Press Wire

Fortunately, civil society too organised numerous side events, where it was also pointed out that in Seville, much old wine was being put into old wineskins. Daniela Gabor, for example, economist and member of the UN Expert Group on Financing for Development, recalled that already in 2015, the World Bank came up with its motto "from billions to trillions" in regard to funding implementation of the Addis Ababa Action Agenda (the outcome of the third financing for development conference). Public-private partnerships and de-risking were already central pillars of the Agenda at the time. The idea was (and still is) to use taxpayer funds from the international cooperation (IC) budgets of the Global North to create "investable projects" for large investors like BlackRock or pension funds. In reality, this meant assuming risk so that such investors could garner attractive "risk-adjusted returns" on their investments in water, road or energy projects.

That most certainly did not work and – according to Gabor – not for a lack of sufficient funds for de-risking from multilateral development banks, the EU or the Biden administration. It failed because even with tax monies being used to fund risk-taking, major projects were still much too costly for the countries in the Global South.

Meanwhile, the "small is beautiful" version of de-risking has emerged, whereby "impact" investments are to be promoted for implementing individual SDGs, and not just for major infrastructure projects. They are meant to reach "beneficiaries" in the Global South directly. However, beneficiaries must also pay for renewable energy, for instance, as the returns have to come from somewhere. IC terminology notwithstanding, the “beneficiaries” are in fact no more than clients and borrowers. It is this version of the de-risking agenda that Switzerland, too, is also promoting.

Objections were forthcoming not just from civil society, but also from government representatives from the Global South. South Africa's Planning Minister Maropene Ramokgopa, for example, urged realism and recalled that the private sector only plays a part where a profit can be made, and that "blending" cannot therefore replace concessional funding especially in the prevailing debt situation. In addition, an event held by Small Island Developing States highlighted entirely different risks that ought to be of pivotal importance. They were not the risks to investors, but those confronting people as a result of sea level rise. This is where "de-risking" is needed.

No one disputes that the "private sector" and the super-rich possess considerable assets that could be harnessed for realising the SDGs and implementing the Compromiso. Still, there are means other than hoping to lure them with scarce IC funds or relying on their philanthropy. Luckily, that too could be heard in Seville. If one wanted to hear it. Switzerland did not.

"Domestic Resource Mobilisation" is another key plank of the "Compromiso de Sevilla". More tax revenue enables the countries of the Global South to depend less on development funding and to develop their economy and society from the inside out.

This could have been heard from Aminata Touré, former Prime Minister of Senegal: "When it comes to taxes, there is an ongoing injustice from which Africa has suffered for centuries. (…) We have debts because of tax avoidance and evasion, (…) because European multinationals exploit our commodities and pay no taxes. (…) This is why the African Union is so strongly committed to a binding UN tax convention. We want a fair distribution of the right to tax. Taxes should be paid where wealth is created. That is hard to explain because it is so simple. Every school child understands that the richer you are, the more taxes you pay.

A German Finance Ministry representative had a remarkably similar message: "Steadily diminishing development finance creates an even greater need for more decisive measures against illicit financial flows, the German government has long been committed to this. Corporations and the super-rich must make their fair contribution towards the global tax pie."

Nobel Prize Laureate in Economics Joseph Stiglitz underlined other key aspects of the tax agenda: “The USA is now paying part of that price [of inequality] with the capture of our government by the techno-oligarchs. That agenda of (…) letting the rich escape taxation, of cutting taxes for the oligarchs, Trump wants to make global. (…) But the world can’t be held hostage, (…) there can be coalitions of the willing. (…) There’s been a very a rich discussion here of the rationale for why we ought to be taxing the super-rich. It’s obvious you don’t need to have a Nobel Prize to figure that out. (…) We’ve created tax havens around the world. (…) We could have regulated them. (…) We allow them to exist. (…) There are some special interests who benefit from them. We need global norms, we need global rules”.

Such coalitions were already emerging in Seville. Spain and Brazil announced a joint initiative for the global taxation of the super-rich. Nine countries – Brazil, France, Kenya, Barbados, Spain, Somalia, Benin, Sierra Leone and Antigua and Barbuda – are willing to commit to introducing a "solidarity levy" on business and first-class flight tickets and on private jets.

The "Sevilla Platform for Action" through which the Seville "Commitment" is to be implemented, contains these and 130 other voluntary initiatives. There is something of a contradiction between commitment and voluntary action, but considering the state of multilateralism, even a list setting out some good suggestions represents progress.

Although the "Compromiso de Sevilla" is non-binding, the "platform" voluntary, and key topics are missing, the conference did show that there are various coalitions of European, African and Latin American countries pursuing solutions. Switzerland should draw up the following to-do list as a pragmatic minimum programme:

Those who prefer less pragmatism can find comprehensive problem-solving suggestions available Alliance Sud’s latest publication “The New Deal – A New Switzerland for a Just World”.

Share post now

global

The Alliance Sud magazine analyses and comments on Switzerland's foreign and development policies. "global" is published four times a year (in german and french) and can be subscribed to free of charge.

Article

29.06.2025, Financing for development, Climate justice

At the UN conference in Seville, the future direction of international financial institutions is also at the centre of discussions. However, the development of the World Bank remains far from the urgently needed revolution.

The idea of attracting private capital on a large scale to finance roads, hospitals and other urgently needed infrastructure projects in the poorest countries also proved to be an illusion at the World Bank. © Shutterstock

In 2015, the World Bank launched a new strategy and vision – the “Forward Look: A Vision for the World Bank Group in 2030”. This was the birth of the Maximize Finance for Development approach, which aimed to massively increase private finance for development through sectoral and policy reforms, as well as the use of guarantees and various de-risking instruments. As a result, the slogan “from billions to trillions” became a much-repeated mantra in the broader development community. Fast forward to 2023 – the World Bank initiated a strategy process termed the “Evolution Roadmap”, which is supposed to make it better equipped to address modern development challenges and to renew its credibility. While the Evolution Roadmap changes the World Bank’s mandate and mission to include major global challenges, most notably climate change, operationally and financially, it is more a deepening and a continuation of the Maximize Finance for Development Approach (despite the fact that the “billions to trillions” slogan has in the meantime been debunked as a myth even by notable World Bank economists).

Indeed, ten years after the launch of the slogan “from billions to trillions” – “well-meaning but silly” according to the CEO of the Private Infrastructure Development Group (PIDG), Philippe Valuhu, recently quoted by the FT, progress in finding private finance to fill the ever-growing funding gap (4,000 billion a year for the SDGs not counting climate financing needs) – has been very disappointing. The basic idea to use public funding to attract large amounts of private money, particularly from institutional investors did not materialize. The (over-) simplistic hope was that pension funds and insurance companies in rich countries would line up to finance roads, hospitals and other basic infrastructure sorely needed in developing countries.

Originally, when the slogan “from billions to trillions” was launched, the assumption was that every public dollar could leverage two or more private-sector dollars. Such a “leverage ratio” is only achieved in rare cases. A recent ODI study shows that “blended concessional finance” – i. e. public capital (mainly provided by MDBs) at below-market rates – attracted, in 2021, for every dollar, some 59 cents of private co-financing in Sub-Saharan Africa – the region where needs are greatest – and 70 cents elsewhere. Multilateral development banks (MDBs) and development finance institutions (DFIs) have been and remain at the forefront of these “mobilization” efforts. By 2023, they together succeeded in mobilizing some 88 billion USD of private financing for middle-income and low-income countries (MICs and LICs), out of which 51 billion were mobilized by the World Bank Group (including its private sector arms IFC and MIGA), representing around 60% of the total amount of private financing mobilized. However, only 20 billion USD were mobilized for sub-Saharan Africa and only half of this reached the poorest countries (LICs). By way of comparison, the region received USD 62 billion in aid in the same year. Furthermore, more than 50% of these private funds went to just two sectors: banking and business services, and energy. By comparison, education and health and population together received less than 1%.

While the evidence is obviously disappointing, the amount of financing that MDBs should be able to “crowd-in” for development projects has become an idée fixe for donors and other stakeholders. So, the dream goes on, and the level of ambition has been raised considerably under the Evolution Roadmap. Although the WB's current president, Ajay Banga, has admitted that the “billions to trillions” formula is unrealistic, and its chief economist, Indermit Gill, has called it a “fantasy”, the Bank is experimenting with new and increasingly sophisticated models, including the bundling of loans into financial products that are then sold to private investors – a practice known as securitization, with the aim of freeing up capital to issue more loans.

New instruments are constantly being developed and praised for their potential to attract private capital: the idea is to extend the use of risk-sharing instruments such as guarantees, new investment vehicles and insurance solutions to mobilize private capital. The World Bank's most recent products are “outcome bonds”, aiming at mobilizing funding from private investors for projects in developing economies, by transferring performance risks to investors who are then rewarded if the underlying activities are successful.

Under the Evolution Roadmap, the World Bank has changed its vision to add “on a liveable planet” to its existing twin goals of eradicating extreme poverty and boosting shared prosperity. In line with this addition, it has positioned itself as a key player in achieving the new climate finance target agreed to at the COP29 in Baku. According to a statement released before the conference, the “World Bank Group is by far the largest provider of climate finance to developing countries”. In 2024, it reportedly delivered 42.6 billion in climate finance (amounting to 44% of its total lending). While there are also significant problems with regards to accounting and transparency of WB climate finance, this article focuses primarily on climate finance as part the broader privatisation agenda pursued by the WB.

As the World increasingly looks to multilateral development banks as providers of climate finance, the focus shifts away from much-needed public finance solutions. A recent analysis by the Bretton Woods Project highlights how the World Banks climate finance is deeply embedded in its broader privatisation agenda. This is also particularly visible in its development policy financing (DPF), which in 2023 accounted for 22% of IDA and IBRDs (the WB organisations in charge of providing loans and grants to poor and middle-income countries) climate finance. DPF is a form of non-earmarked, fungible budget support that is linked to concrete policy reforms (prior actions). Most of the prior actions required were linked to market-based reforms, including de-risking measures for private investment or the removal of consumer subsidies on fossil fuels (which are found to have a particularly punitive impact on the poorest segments of populations).

Furthermore, the majority of MDB climate finance comes in the form of loans, rather than grants, thus increasing the debt burden of already highly indebted countries. In fact, in 2023, loans accounted for 89.9% of IBRD and IDA climate finance (the two WB organisations that account for the largest share of WB climate finance). The fact that these loans – which by definition have to be paid back with interest – are also attributable to the climate finance of WB member states also stands in sharp contradiction to the “polluter pays” principle.

The WB Evolution Roadmap is hence far from a revolution in terms of its private sector agenda but could be classified as “more of the same, including climate”. However, the expansion of climate finance is now being severely challenged by the new US administration. While recently reaffirming its commitment to the WB (and IMF), Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent called for a return to its core mandates and reforms of “expansive” programs. The Bank should support “job-rich, private-sector-led economic growth”, and move away from its social or climate programs. Mr. Bessent stressed that the Bank should be “technology neutral” and prioritize the affordability of energy investments. In most cases, this means “investing in the production of gas and other fossil fuels”. In order not to offend the new US administration, the Bank has become rather silent on its climate agenda and following a request by the US has recently decided to end its moratorium on nuclear energy and a vote on reintroducing financing for the exploration and extraction of gas should follow in the near future. Whether the US administration will be able to force the WB to reverse the expansion of its vision and mandate and to move away from its “Paris alignment” commitment or whether the European chairs will be in any position to oppose such disastrous decisions, as well as what role Switzerland will play, remains to be seen.

As the World’s development community gathers in Sevilla to discuss the future of development finance, some of the sticking points may become clearer. Once more the “Sevilla compromise” highlights the enormous financing gap of 4 trillion USD needed to reach the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030. While it acknowledges that “private investment in sustainable development has not reached expectations, nor has it adequately prioritized sustainable development impact”, the document goes on to outline a broad set of measures aimed at “increasing the mobilization of private finance from public sources by strengthening the use of risk-sharing and blended finance instruments”, with MDBs playing a key role in this agenda. While the frantic search for new instruments and ways to make development and climate projects “bankable” and thus more appealing for private investors continues, the debt crisis takes on speed and the role of the public sector as a provider of much-needed development and climate finance is further weakened.

According to the World Bank chief economist Indermit “since 2022, foreign private creditors have extracted nearly $141 billion more in debt-service payments from public-sector borrowers in developing economies than they have disbursed in new financing.” Today, several African countries spent more than half of their resources on debt repayment and Indermit event admits that some countries simply use World Bank loans (which have a longer maturity rate) to pay back their private creditors, thereby diverting scarce resources “away from areas critical for long-term growth and development, such as health and education”.

While private capital certainly can and should play a role in sustainable development and climate finance, it is time to abandon simplistic solutions and to address the root causes of current multiple crisis. This would include a much-needed reform of the WBs governance structure to give countries in the Global South more decision-making power, as well as broad-based debt restructuring and cancellations, as well as investments in domestic resource mobilisation and a fairer global tax system with the aim to combat rising inequalities world-wide. It does not look like Sevilla will be the place, where the much-needed revolution starts, but the fight goes on.

Share post now

Impact Investing

21.03.2025, Financing for development

Advocates of impact investing portray it as one way to help fund both the Sustainable Development Goals and climate targets. In a recent study, Alliance Sud took a closer look at this contribution, which to date remains rather limited.

Few investments are made in the poorest countries, as they are considered too risky. A farmer in Guerou, Mauritania, uses solar panels to irrigate his pastures. © Tim Dirven / Panos Pictures

It is no secret that Switzerland aims to become a leader in the realm of sustainable finance. At the heart of "sustainable" finance is impact investing, with a twofold ambition, namely, ensuring "market-based" financial returns, while also helping to resolve global social and environmental challenges. Laid out for the first time in 2007 by the Rockefeller Foundation, this approach has since gained many public and private followers in the international financial system; their shared objective is to "mobilise" private capital in order to attain the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Some even see this as a way of cushioning the cuts to Official Development Assistance (ODA) budgets. Yet, there is a yawning financing "gap" for achieving those goals. According to UN Trade and Development (UNCTAD) based in Geneva, developing countries are grappling with an annual funding gap of more than USD 4000 billion. Of this amount, some USD 2200 billion are needed to fund the energy transition alone.

To put things into perspective, at the end of 2023, Swiss banks – the leaders in cross-border wealth management – were managing some CHF 8,392 billion. Hence the somewhat simplistic question: what portion of this wealth could be invested in developing countries to fund the SDGs?

In its “Sustainable finance action plan”, the Federal Council aims to extend access to impact investing to include private capital, going beyond just private foundations and family offices, and this "on a large scale" in order to fund projects that make a "measurable and credible contribution to the aims of sustainability". In parallel, it also aims to create new economic outlets for Switzerland's asset management industry. In other words, impact investing is to be brought out of its niche and made accessible and attractive to institutional investors, including pension funds, which are seeking, or must secure a financial return acceptable to the market.

In parallel, Switzerland's international cooperation funds – which Parliament reduced in December last, let us recall – are being deployed, as part of blended finance, to reduce investment risks and so render impact investing financially more attractive. The hope is that this risk reduction will have a "demonstration effect" and attract the aforementioned institutional investors on a larger scale.

To examine the plausibility of these expectations, Alliance Sud used a recent study to present Switzerland's impact investing market, that is to say impact investing managers based in Switzerland and deploying capital in developing countries. This market comprises some 18 players managing almost USD 15 billion in assets. Of this amount, some USD 11 billion comprises "private" assets, in other words investments in shares and bonds issued by private enterprises in developing countries – in contrast to "public" enterprises, which are listed on the stock exchange.

To put this figure into perspective, this amount represents less than 0.6% of the global volume of "sustainability-linked investments" (according to the definitions applied by the Swiss Sustainable Finance association), or 0.116% of the total volume of assets under management (AuM) by Swiss banks at the end of 2023 (the roughly CHF 8400 billion mentioned above).

Countless European banks are involved in low-risk, high-return projects such as the Cerro Dominador solar power plant in the emerging nation of Chile. © Fernando Moleres / Panos Pictures

This market is highly concentrated, with its three leading players – responsAbility, BlueOrchard and Symbiotics, now all foreign-owned – controlling 80%. In regional terms, these investments are concentrated mainly in Latin America and the Caribbean (24%), and also in Eastern Europe and Central Asia (20%), given the relative political and economic stability and an investment-friendly environment. Sub-Saharan Africa, on the other hand, receives only 13% of overall investments, while the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) receives a mere 2%, reflecting less attractive investment conditions and risks perceived as too high in these regions.

One half of impact investing is concentrated in 10 countries. India heads the list with 15% of overall exposure, followed by Cambodia, Georgia, Ecuador and Vietnam. All told, 35 countries account for 85% of the investments (taking into account only countries with at least 1% exposure). As of 2025, only 14 of these 35 countries are priority countries for Swiss international cooperation. In income terms, one half of them consists of upper middle-income countries. Only four are least developed countries (LDCs), i.e., Cambodia (6%), Bangladesh (2%) – countries from which the SDC has announced its withdrawal as of 2025 following budget cuts – Tanzania (1%) and Myanmar (1%).

The Swiss impact investing market is also highly concentrated in terms of sectors. Microfinance dominates the market, accounting for about half of total assets under management. The two sectors of microfinance and SME development account for more than 80% of investments, reflecting their financial performance. The sectors of food and agriculture as well as climate and biodiversity receive significantly less investments – with 10% and 4% respectively – despite their substantial financial needs. The "social sectors", including housing, water supply, healthcare and education, together attract less than 2% of the capital. This is due mainly to the fact that these sectors generally do not offer attractive financial returns and are often managed by governments as public goods.

The Swiss impact investing market therefore tends to be concentrated in regions and sectors that offer lower risks and higher financial returns. This reflects a broader trend towards "safe" investments, which does not necessarily address the more urgent challenges of sustainable development. In its conclusions, the Alliance Sud study underlines the fact that impact investing obviously cannot by itself offset the deficit in funding for achieving the SDGs. It is therefore crucial to prioritise the mobilisation of domestic resources, the fight against illicit financial flows and the maintenance of substantial official development assistance for the poorest countries.

Share post now

global

The Alliance Sud magazine analyses and comments on Switzerland's foreign and development policies. "global" is published four times a year (in german and french) and can be subscribed to free of charge.

Private climate finance

05.12.2024, Financing for development, Climate justice

Many people favour greater use of private funding to cover current and future contributions from the countries in the North to those in the South in their fight against climate change. A stocktake by Laurent Matile

Correcting inflated expectations: An initiative launched by Barbados' Prime Minister Mia Mottley to promote climate finance for developing countries has scaled back its demands on the private sector. © Keystone / AFP / Brendan Smialowski

"The numbers that are thrown around about the potential of green capital mobilization are illusory. [...] There is a lot of piffle in this area." These were some of the remarks made by Lawrence H. Summers, former US Treasury Secretary and President Emeritus of Harvard University, in wrapping up a panel discussion in Washington D.C. last October.1

At COP29 in Baku, which ended on 24 November, a new climate financing goal was agreed at the last minute: developed countries have pledged to triple funding, from the previous target of USD 100 billion per year to USD 300 billion per year by 2035. This is far too little in view of the needs of developing countries, which are estimated to total USD 2,400 billion a year. In a nebulous formula, it was further agreed to ‘secure the efforts of all actors’ to increase funding for developing countries, from public and private sources, to 1.3 trillion dollars a year by 2035.

Despite not being central to the COP29 agenda, mobilising private climate finance is still considered the silver bullet by many public and private players. The definition of "climate finance" does not in fact specify what portion must be covered by public and/or private funding. This vagueness has spawned much uncertainty as to the source of the funds being allocated to climate, and allows governments ample leeway in meeting their commitments. And there is great temptation to use private funds to fill the public funding gap.

The fact is that since the conclusion of the Paris climate agreement in 2015, many public and private players – the ones Lawrence Summers has in mind – have stepped up their efforts to advocate for the design of "innovative financial instruments" that benefit from public subsidies and invariably pursue the same aim: that of de-risking in order to "catalyse" private investments, whether for the climate or for sustainable development. And this credo is not about to disappear. In the back of their minds, numerous delegations, including Switzerland, are thinking that whatever the final amount owed by each developed country, it will be possible to secure a substantial part of it by "mobilising private capital".

Let us consider for a moment the current state of climate finance in developing countries. The latest OECD2 figures show that:

The OECD recalls (time and again) that "a number of challenges may affect the potential to mobilise private finance" to combat climate change in developing countries. These include the general environment that may be enabling (or not) for investment in beneficiary countries, the fact that many climate projects are not profitable enough to attract large-scale private investment; or, the fact that individual projects are often too small to obtain significant commercial funding.

Few ideas seem as hackneyed as the hope that a few billion dollars in public funds will be able to mobilise trillions in private investment for sustainable development and climate protection. This credo is increasingly being challenged, and not just by non-governmental organisations.

The Bridgetown Initiative 3.0, for example, has reassessed its expectations regarding the mobilisation of the private sector. Launched in 2022 by Mia Mottley, the charismatic Prime Minister of Barbados, the third version of this initiative was published in late September. It aims to rethink the global financial system in order to reduce debt and improve access to climate finance for developing countries. While Bridgetown 2.0 called for over USD 1.5 trillion per year to be mobilised from the private sector for a green and just transition, version 3.0 has scaled back the amount being requested to "at least USD 500 billion".

In the light of the outcomes in terms of the volumes and characteristics of private finance mobilised to date, a number of conclusions can be drawn:

Position of Alliance Sud

First, Alliance Sud is calling for most of Switzerland's "fair share" to international climate finance to be provided through public funding – with a balance between funds allocated to mitigation and those allocated to adaptation. Second, the call is also made for private funding mobilised through public instruments to be counted towards Switzerland’s climate finance only if its positive impact on people in the Global South can be duly demonstrated.

1 CGD Annual Meetings Events: Bretton Woods at 80: Priorities for the Next Decade, Washington D.C., October 2024.

2 Climate Finance Provided and Mobilised by Developed Countries in 2013-2022, OECD 2024.

Share post now

global

The Alliance Sud magazine analyses and comments on Switzerland's foreign and development policies. "global" is published four times a year (in german and french) and can be subscribed to free of charge.

Study

10.12.2024, Financing for development

Impact Investment has gained popularity, particularly in Switzerland, a country known for its financial system and its aspirations for sustainable finance. As impact investing is often presented as a panacea for development challenges, Alliance Sud’s study takes a critical look at its effectiveness, its limitations and the extent to which it can contribute to sustainable development.

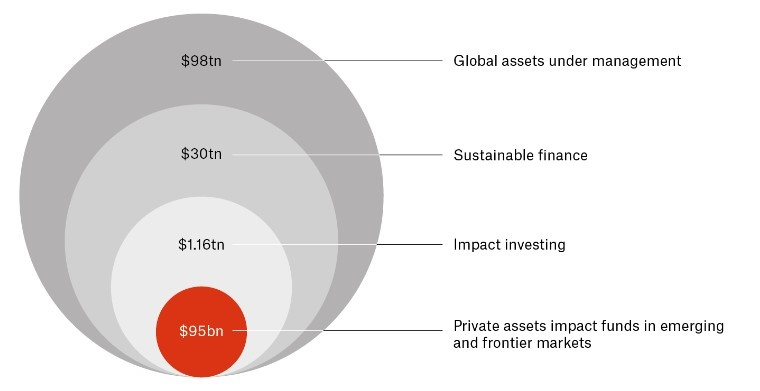

Impact investing, while growing, remains a niche market globally,

particularly in developing countries. Source: Tameo 2023.

Share post now

REBUILDING UKRAINE

03.10.2024, Financing for development

The Federal Council wants to allocate to the Swiss private sector 500 million earmarked for reconstruction in Ukraine. This certainly does not serve the interests of Ukraine's economy and enterprises.

Large Ukrainian steelworks such as Zaporizhstal have been attacked or occupied and are barely able to maintain their production volumes. © Keystone/EPA/Oleg Petrasyuk

Speaking at the Ukraine Recovery Conference (URC) in Berlin on 11 June last, Federal Councillor Ignazio Cassis laid out Switzerland's commitments: "First, the private sector plays a key role in the reconstruction process. Switzerland is promoting sustainable framework conditions and ensuring that small and medium-size enterprises (SMEs) can function and remain competitive". In cooperation with the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), Switzerland announced its support for a new mechanism to protect private investments against war risks, and its intention to join an alliance to support SMEs. One therefore had reason to believe that the Swiss Foreign Minister's intention was to give priority support to Ukrainian companies and the Ukrainian economy.

Two weeks later, however, on 26 June, the Federal Council announced that "Switzerland's private sector should play a key role in Ukraine's recovery efforts". The Federal Council plans to allocate CHF 500 million for that purpose over the next four years, that amount coming from the budget of CHF 1.5 billion earmarked for Ukraine in the International Cooperation Strategy 2025-2028. Almost the entire sum will be transferred from bilateral development cooperation funds at the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) to the State Secretariat for the Economy (SECO). The "Ukraine country programme" as a whole will be managed by Jacques Gerber, currently Councillor of State for the PLR in the Canton of Jura, who will be attached to the General Secretariat of the FDFA as Delegate for Ukraine, and will report directly to Federal Councillors Cassis and Parmelin.

As far as we are aware, the SECO plans comprise two phases. First, support is to be given to Swiss companies already operating in Ukraine to enable them to create or maintain jobs. To this end, the federal government must cover the risks faced by those companies, for example, through financial assistance or insurance solutions. The justification given for using international cooperation funds is that the projects of companies being supported must include a "development component", for example vocational training programmes. So far nothing is clear, but some potential beneficiaries are being mentioned, including the glass manufacturer Glas Trösch. Moreover, some measures are meant to incentivise Swiss companies not yet active in Ukraine to invest there. That could crowd-out Ukrainian SMEs and companies.

The second phase, in which SECO envisages giving preference to the Swiss private sector in general, is even more problematic. Ukraine would receive money from Switzerland which it could then only use for procurement from Swiss companies. This tied aid is at odds with best practices of international cooperation, WTO provisions, and with Swiss law on public procurement. There is no legal basis for that practice, and it would therefore have to be created in the coming months. For the Federal Council, an international agreement with Ukraine would suffice, while the Foreign Affairs Committee of the Council of States has called for a specific law. During its winter session, the Parliament will take the final decision on the package as a whole in the context of the International Cooperation Strategy. The decision by the Federal Council to grant preferential treatment to Switzerland's private sector is obviously not consistent with the promises made in Berlin, however. The fact that Ukraine is free to decide for itself what it needs from Swiss companies is not a convincing argument. In an emergency, you will accept a supermarket voucher even if it is disadvantageous to your own village shop, which you should be supporting.

What Ukraine needs is support from the international community – which should include Switzerland – for its economy and its companies, the backbone of which comprises small and medium-size enterprises (SMEs) – some 90% – which are showing exceptional resilience despite the uncertainties of the war. A recent study by the London School of Economics1 has found the Ukrainian economy to be remarkably resilient, but that growth prospects will remain weak for as long as the war continues. Ukrainian producers are losing domestic market share to international competitors that are not operating in wartime conditions. This represents a loss to Ukraine that gives cause for concern and illustrates that the country’s relatively open economy (especially vis-a-vis the EU, through the Association Agreement) is ill-suited to wartime conditions. In the circumstances, increased State purchases of goods and services (through public procurement) from Ukrainian private enterprises is a crucial tool for boosting the resilience of Ukraine's wartime economy by supporting production capacity and employment while laying the groundwork for future recovery and reconstruction.

Partners, including Switzerland, must therefore support a "localisation offensive" to guarantee and build national capacities. They should support the Ukrainian Government's "Made in Ukraine" subsidy programme, which is designed to boost national production. They should set the example by making local content stipulations a condition for providing financial aid to Ukraine, so that aid going to Ukraine is spent in Ukraine. Efforts should also be made to favour technology transfer to the Ukrainian economy. Not only would this boost fiscal receipts, but thanks to increased exports, also foreign exchange receipts, both of which will be needed to repay the reconstruction loans granted by the international community (mainly the EU).

Moreover, Western countries should encourage cooperation between their enterprises and Ukrainian ones for goods production (through joint ventures or consortiums, for instance), using mechanisms that insure against war risks, and providing favourable funding. In the short term, that could boost the resilience of Ukraine’s wartime economy and, over the medium-to-long term, facilitate its integration into global value chains. The measures in the first phase of Switzerland's plans would therefore be meaningful, if the appropriate framework conditions were met.

Reconstruction planning should take account of the green transition, which would both make Ukraine's economy sustainable and facilitate alignment with the EU's Green Deal. Investing in clean energy would be indispensable, as would be efforts to decentralise energy production (Ukraine has a large number of small electric power plants), which renders the industry less vulnerable to Russian strikes. Foreign partners and investors should help Ukrainian enterprises that are lacking in capabilities and human capital to deploy cutting-edge technology, including zero-emission technologies. SECO's plans could also contribute to this.

There is nonetheless an appreciable shortage of funding for modernising Ukraine's industries and for reconstruction, including in the construction materials and metalworking industries, and for decarbonising their structures, some of which date back to the Soviet era. Creating a Ukrainian development bank could provide the long-term capital needed for such re-industrialisation projects. Western partners, including Switzerland, should support Kiev in its quest for funds and provide the requisite guarantees for the large-scale funding of Ukrainian companies.

Ukraine's burgeoning raw materials sector demonstrates the need for both increased funding and a targeted industrial policy. In Berlin, EU representatives hailed Ukraine's huge reserves of ‘critical raw materials’, which the European Commission considers to be crucial to the European economy. Ukraine is said to have 22 of the 34 minerals identified as essential for ensuring the EU's ‘strategic autonomy’, or even ‘European sovereignty’. A Ukrainian development bank could help national companies to become players in this emerging sector and maximise value creation in Ukraine.

It is clear to Alliance Sud that some measures in the first phase of SECO's plans could be wise, if they create jobs, facilitate technology transfer – especially "green" technology – and entail partnerships with local companies, and if it is ensured that promoting Swiss companies does not mean crowding out Ukrainian ones. There is an urgent need for transparent reporting on specific plans so that their utility or their undesirable effects can be assessed. Switzerland's aid should nevertheless focus on support for the local private sector and the Ukrainian economy. That would require funding first and foremost; Switzerland would do better to use existing multilateral channels instead of going it alone.

The second phase, which is designed solely to secure a "piece of the reconstruction cake" for the Swiss export sector, would clearly run counter to the interests of the Ukrainian economy. Yet, a Ukrainian economy with long-term stability is more beneficial to Switzerland than full order books for some companies in the short term. These plans should therefore be stopped. Clearly, these activities are only marginally in line with Switzerland's international cooperation priorities and should therefore not be funded from the international cooperation budget.

1 A state-led war economy in an open market. Investigating state-market relations in Ukraine 2021-2023. LSE Conflict and Civicness Research Group, 4 June 2024.

Share post now

global

The Alliance Sud magazine analyses and comments on Switzerland's foreign and development policies. "global" is published four times a year (in german and french) and can be subscribed to free of charge.

Article, Global

21.03.2024, Financing for development

In October 2023, the OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC) took a decision that has largely escaped public notice. It is about including "private sector instruments" in development financing, and could hold far-reaching implications for the poorest countries in the South.

© Christina Baeriswyl

The way of measuring development funding has been a topic of discussion since its inception. While donor countries in the North wish to be seen as being as generous as possible, countries in the South want the biggest possible share of the funds to go where it is most needed. This is the backdrop to the current debate on the inclusion of public contributions for loans and various types of investment in enterprises located in countries of the South.

In February 2016, and as part of the process of "modernising" the definition of Official Development Assistance (ODA), members of the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) agreed for the first time on principles by which to account for Private Sector Instruments (PSIs). These instruments include loans to enterprises, equity investments, mezzanine financing1 and guarantees.

At the time, however, DAC members failed to agree on the rules that would govern the inclusion of PSIs in ODA, in accordance with the principles agreed. Provisional reporting methods were therefore put in place in 2018. As PSIs represent just 2-3 per cent of total ODA, the solution was deemed acceptable while the DAC worked to find a more permanent solution. In October 2023, a new permanent agreement was reached on PSIs, with potentially far-reaching consequences for development financing.

Since the introduction of ODA in the 1960s, one of its key principles has been that of concessionality. Under this principle, development funds are exclusively grants, or take the form of preferential loans. The OECD-DAC decision of October 2023 supplanted this principle and redefined ODA. The new rules require that when private sector instruments are included, evidence must be presented regarding the role of the funds allocated to these instruments in adding value, whether financially or in terms of content and development (see “The three definitions of additionality”). DAC member countries are expected to provide information on the type of additionality of the PSIs they use. This is mandatory.

But the DAC itself regrets that the data provided so far has been sketchy and that the additionality reports submitted are "incomplete and unconvincing". Yet, solid reporting on additionality is the key to ensuring that DAC members effectively allocate scarce ODA resources where the needs are greatest, and where they can be most impactful.

For a PSI activity to qualify as ODA, it must provide additionality at the financial level or in value and development terms:

In the absence of adequate additionality reporting, however, one can only make presumptions about, rather than demonstrate the added value of PSIs. In other words, without this information, there is the risk that ODA could be artificially "inflated" by creative accounting practices, and this would increasingly water down the definition of "development assistance". On a seemingly positive note, as of 2026, information provided on the additionality of PSIs will undergo special examination by the DAC Secretariat "to enhance the integrity of ODA". It is to be hoped that these verifications will make for greater transparency.

According to a Eurodad study, between 2018-2021, a total of USD 20.6 billion was reported as PSIs, representing 3 per cent of total ODA. By themselves, the four main European countries (UK, EU, Germany and France) account for 80 per cent of the total of PSIs from DAC members. Switzerland ranks 11th, with 0.7 per cent of the total.

Eighty-five per cent of the total was channelled through Development Finance Institutions (DFIs), including the Swiss Investment Fund for Emerging Markets (SIFEM) in Switzerland. The respective DFIs of the four major European donors – British International Investment (BII) in the UK, the European Investment Bank (EIB/EU), the Kreditanstalt für den Wiederaufbau (KfW) and the Deutsche Investitions- und Entwicklungsgesellschaft (DEG) in Germany, and France's Proparco – account for 91 per cent of all PSI ODA reported by these DAC members. Some of these DFIs have seen their portfolios double in the space of ten years, and the amount of DFI activity is expected to grow further in the years ahead.

Source: OECD-DAC Creditor Reporting System 2023.

These development finance institutions have a profitability mandate and therefore invest preferably in countries and regions with a lower risk profile and more secure profit expectations. As the figure above illustrates, between 2018 and 2021, most of the private sector instruments were invested in upper middle-income countries (59 per cent), followed by lower middle-income countries (37 per cent). Only 4 per cent of PSIs were allocated to least developed countries (LDCs). This shows that only marginal amounts of the development funds managed via PSIs reach the countries most in need.

Switzerland reports some CHF 35 million as ODA in the form of PSIs, which include capital payments of CHF 30 million per year to SIFEM, plus a few other instruments (less than CHF 5 million). SIFEM specialises in the long-term funding of SMEs and other "fast-growing" enterprises, in order to stimulate economic growth and create jobs.

A distinction must be drawn between PSIs and "amounts mobilised from the private sector", in other words, all private funding mobilised through public development finance interventions, regardless of the origin of the private funds. These funds are not part of ODA, but may be included in the broader indicator of development financing – total official support for sustainable development (TOSSD).

In its latest edition, the 2023 DFI Transparency Index – which analyses the activities of the 30 leading DFIs with assets totalling USD 2000 billion – SIFEM occupies a very low position in the transparency rankings! At the close of 2022, SIFEM's investment portfolio amounted to USD 451 million, and was allocated almost entirely to middle-income countries (MICs). More specifically, 62 per cent was invested in lower middle-income countries and 34 per cent in upper middle-income countries. Low-income countries (such as Ethiopia and Malawi) accounted for just 3 per cent of the investment portfolio. As of the same date, only 42 per cent of the portfolio was invested in priority countries for Switzerland's international cooperation.

We are witnessing a critical period where wars, the fallout from the coronavirus pandemic and the growing impacts of climate change are plunging millions of people into poverty. Donor-country resources are remaining flat or diminishing, and are therefore being used to cope with a growing number of crises and wars. This raises the question as to whether the development of private sector instruments, the vast majority of which are allocated to better-off developing countries, is the ideal path for Switzerland's international cooperation (IC). The current database is not sufficient to allow for a definitive assessment of the effectiveness of these instruments. But the current geographical distribution is such that we question whether private sector instruments are contributing to the constitutional mandate of IC – i.e., to assist those in need and combat poverty in developing countries and regions, and to favour the most disadvantaged population groups. These instruments should therefore not play a pivotal role in Switzerland's international cooperation, also in the future. But it is much more crucial to ensure that the modernisation process does not further dilute the principal benchmark for development financing, i.e. ODA, and that Pandora's box is closed once again.

1 The OECD defines mezzanine financing as instruments relating to types of financing that fall between an enterprise's senior debt and equity, displaying features of both debt and equity.

Share post now

global

The Alliance Sud magazine analyses and comments on Switzerland's foreign and development policies. "global" is published four times a year (in german and french) and can be subscribed to free of charge.

Article, Global

10.12.2020, Financing for development

The 2030 Agenda rests on what is hitherto the most ambitious funding strategy for sustainable development. Is it realistic to think it possible to raise trillions for the sustainable development goals?

A worker controls beer production in Beni, Democratic Republic of Congo. It is questionable whether private investors also have poverty reduction in mind. © Kris Pannecoucke / Panos

In addition to public funds, private funding sources – domestic and foreign – are deemed indispensable. This is even viewed in some circles as the ideal way of meeting the funding shortfalls. More specifically, these private funds encompass private investments as well as philanthropy and remittances.[1] In its International Cooperation Strategy 2021-2024, the Swiss Government advocates for diversifying and scaling up cooperation with the private sector; it envisages deploying Official Development Assistance (ODA) funds as a means of raising "additional private funds" for sustainable development.

The Blended Finance approach in particular is one of the financial vehicles intended to attract private resources for sustainable development financing. While it has generated very high expectations, the outcomes to date have been rather modest.

Let us try to achieve some clarity on the basis of five questions:

1. Blended Finance: What is it about?

There is no universally accepted definition of Blended Finance. The underlying idea, however, is for funds and other resources (personnel, expertise, political contacts, etc.) from bilateral and multilateral official development aid to be deployed as a "levers" to mobilise private sector investments for development cooperation.

2. What are the currently existing models?

In practice, Blended Finance works as follows: private investors generally aim for a financial return commensurate with the investment risk, in other words, a risk-adjusted return. The higher the risk – real or perceived – the higher must be the hoped-for return to offset that risk.

In public financing (bilateral or multilateral), there are essentially two approaches to attracting private investors to projects that (a priori) do not meet risk-based return expectations. Under one approach, the investment risk to the private investor can be reduced (de-risking); under the other, the potentially yield accruing to the private investor can be increased.

In general, risk reduction through instruments such as guarantees or first loss capital is applied to projects that seem profitable enough but carry a considerable risk of default or loss of value. The yield may be increased by granting preferential loans to the investor to offset certain project costs, or through an equity stake. These are ways of offering an investment incentive to private investors. Another possibility is technical assistance to reduce certain transaction costs (in the form of feasibility studies, for example).

Both approaches – reducing risk and increasing return – are tantamount to subsidising private investors from official development assistance funds.

3. How does this benefit the poorest?

This is the key question. The Federal Act on International Development Cooperation states that such cooperation is meant to support "primarily the poorer developing countries, regions and population groups" (Article 5.2). To this day, however, there is little evidence of any benefit from such blended finance in the poorest countries.

Blended Finance has indeed grown exponentially, but has so far bypassed the least developed countries (LDCs). The bulk of Blended Finance transactions have gone to middle income countries (MICs), where the main beneficiaries are the sectors with the highest return on investment – i.e. energy, financial services, industry, mining and construction. Sectors like education or health are hardly involved.

4. What are the risks?

Blended Finance carries the following risks:

The Alliance Sud Position paper "Blended Finance – Mischfinanzierungen und Entwicklungszusammenarbeit" (in German and French) offers an in-depth analysis of the potential, limits and risks of blended finance and makes some recommendations.

5. What are the alternatives?

The question generally arises as to whether and under what circumstances the use of Blended Finance and partnerships between players from official development cooperation and private enterprises could fulfil the (high) expectations placed on them.

It should be recalled in this connection that the Addis Ababa Action Agenda (AAAA) provides for the mobilisation of domestic public resources as a priority area of intervention for development financing and that combating illicit financial flows is indispensable in this context. Moreover, in developing the private sector, priority should go to local enterprises, especially micro, small and medium-size enterprises (MSMEs) – especially businesses run by women – and to domestic financial markets.

Blended Finance can thus be just one among several financial instruments with which to implement the 2030 Agenda.

[1] Over recent years, remittances – money sent back to their home countries by workers living and working abroad – have skyrocketed. For numerous developing countries, they currently represent the most substantial source of foreign financing, outstripping even Official Development Assistance (ODA) and Foreign Direct Investment (FDI).

A mere 6 per cent of the USD 157 billion in private funding raised between 2012 and 2017 – or USD 9.4 billion – went to least developed countries (LDCs). Furthermore, Blended Finance projects in LDCs tend to attract less private funding.

Some 55.5 per cent of these funds go to the energy and banking sectors, while just 5.6 per cent go to projects in the social sectors.

The modest level of Blended Finance activities in LDCs underscores the fact that like private financing, this form of mixed funding falls on fertile ground in those regions with the smallest obstacles to the mobilisation of capital.

Blended Finance projects have often succeeded in mobilising additional funds, but these have generally had little impact on poverty. It is more often the case that owing to inadequate monitoring and reporting as well as to a lack of transparency, the development impact is not known. All Blended Finance endeavours ought to be based on co-determination by the respective countries. Projects that are guided by the priorities of developing countries and take local and national players on board are more likely to achieve sustainable outcomes.

Source: Financing for Sustainable Development Report 2020. Inter-agency Task Force on Financing for Development.

Share post now

global

The Alliance Sud magazine analyses and comments on Switzerland's foreign and development policies. "global" is published four times a year (in german and french) and can be subscribed to free of charge.

Article, Global

22.03.2021, International cooperation, Financing for development

In implementing the International Cooperation Strategy 2021-2024, the SDC plans to scale up its cooperation with the private sector and strike up new partnerships. How is this impacting developing countries?

Foreign Minister Ignazio Cassis visits a tourism education institute during his trip to Africa in February 2021.

© Foto: YEP Gambia

Working with the private sector is nothing new in the framework of Switzerland’s international cooperation, whether in the activities of the State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (SECO) or the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC).[1] In accordance with Sustainable Development Goal No. 17 enshrined in the 2030 Agenda, that of entering into partnerships in pursuit of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), Swiss international cooperation had already increased involvement with the private sector during the period 2017-2020.[2] So far, however, that cooperation had never been framed within an SDC strategy. This will now change, at least in part.

Published in January 2021, the “General Guidance on the Private Sector in the context of the International Cooperation Strategy 2021–24” lays out the basic principles governing SDC activities in connection with the private sector and outlines various forms of cooperation with private sector players, as well as the associated challenges and opportunities.

Considering that the private sector makes “the largest contribution to global poverty reduction and sustainable development” – especially as pertains to jobs, taxes and “innovative products that increase living standards in developing countries”[3] – the document states that the Federal Department of Foreign Affairs (FDFA) as well as the Federal Department of Economic Affairs, Education and Research (EAER) plan to step up cooperation with the private sector under the International Cooperation Strategy 2021-2024 and the Federal Council’s new 2030 Sustainable Development Strategy.

In this connection, the SDC points out that in addition to official development assistance (ODA) and domestic tax revenues, the 17 Sustainable Development Goals can only be achieved if “private sector investments are successfully mobilised.” The private sector is therefore considered by SDC as “part of the solution” for reaching the global development and climate protection goals.

For the SDC, private sector involvement in sustainable development is focused on the following four areas of activity: (1) Economic policy frameworks: this includes promoting the rule of law as well as responsible business conduct and sustainable investment. (2) Promotion of local companies in the priority countries for Swiss international cooperation, especially small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). (3) Private Sector Engagement (PSE): this entails engaging in partnerships with private sector players from Switzerland and other countries. And last but not least, (4) Public procurement. This area of activity encompasses SDC contracts awarded to private sector players (at home and abroad), which must meet more stringent sustainable development criteria in the future.

According to the SDC, the third area of activity, private sector engagement (PSE) encompasses ways in which Swiss international cooperation can engage with “established" private sector players that “consistently promote” sustainable development. The SDC states that such private sector players – in both the real economy and the financial sector – can contribute to poverty reduction and therefore make interesting partners for international cooperation. They include large companies and multinational enterprises, SMEs, social enterprises, impact investors and grant-making foundations. Each of these categories has its own “specific strengths”. In this connection, the SDC also mentions, for example, NGOs and academic institutions as possible implementation partners.

As stated in the “SDC Handbook on Private Sector Engagement”, the SDC plans, over the medium term, in other words during the implementation of the International Cooperation Strategy 2021-2024, to increase engagement with the private sector as well as the financial volume of its PSE portfolio. In addition to “traditional” PSE approaches, “new financial instruments” are to be developed, whereby the volume of public-private cooperation can be increased also in least developed countries (LDCs) and in fragile contexts.

Although the document mentions that the setting of a quantitative growth objective is not meaningful, it does note that currently some 8 per cent of all SDC-funded projects (bilateral activities and global programmes) entail partnerships with the private sector. Based on a combination of various factors, it is estimated that over the long run, some 20-25% of all SDC operations could be implemented in collaboration with the private sector, in both the bilateral and multilateral spheres. If we take as a baseline value the 2020 volume of spending of CHF 165 million for the roughly 125 existing partnerships, the volume could rise to almost half a billion in annual spending over the long term.

It should be recalled that the International Cooperation Strategy 2021-2024 makes no provision for the increase of the respective credit lines for the funding of these partnerships, but provides for them to be paid for with funds already earmarked for bilateral development cooperation.[4] This means that the increase in partnerships with the private sector will take place at the expense of other forms of cooperation that have been shown to hold implications for poverty alleviation, more particularly programmes in support of essential public services including education and health. It could also negatively impact other forms of private sector support in developing countries, including the promotion of local SMEs.

It is therefore necessary to ensure the developmental impacts of these partnerships and the relevance of the goals being pursued through this kind of cooperation with the private sector. On this point, the “General Guidance on the Private Sector” nevertheless remains vague, or as it stands, fails to convey any clear idea of how SDC plans to guarantee, under such partnerships, the effective fulfilment of its primary mandate, that of combating poverty in priority countries.

The SDC internal handbook lays out various criteria and modalities for cooperation as well as a complex risk analysis procedure. But as always, the devil is in the detail. The SDC will have to ensure that in creating the partnerships, these criteria and processes are effectively observed by all players and not merely ticked off on a list.

Given the clear trend among the Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) and bilateral donors, the SDC could find itself under pressure to “boost” its PSE portfolio without being able to guarantee that these partnerships are consistent with the core objective of the 2030 Agenda, that of “leaving no one behind”.

[1] See external audit report 2005-2014 on the promotion of employment.

[2] See “Switzerland’s international cooperation is working. Final report on the implementation of the Dispatch 2017–20”, p. 7.

[3] This statement must be qualified in many respects. More on this later.

[4] “In the event that the SDC establishes new forms of cooperation with the private sector, a new budgetary credit line could be created and the requisite funding will be drawn from the ‘Development cooperation (bilateral)’ credit.” IC Strategy 2021-2024, p. 35.

Share post now

global

The Alliance Sud magazine analyses and comments on Switzerland's foreign and development policies. "global" is published four times a year (in german and french) and can be subscribed to free of charge.

Press release

16.03.2022, Financing for development

There is a new SECO initiative designed to mobilise private capital for developing countries. It raises several questions about governance and development impacts.

The two faces of the private sector: on the one hand, it is transporting aid supplies from Zurich to Venezuela in the summer of 2020; on the other hand, Swiss banks are doing business with the elite of the crisis-ridden country, as the "Suisse Secrets" have shown. © KEYSTONE / POOL / Ennio Leanza

On 1 December 2021, the State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (SECO) unveiled the SDG Impact Finance Initiative, a new "public-private partnership for innovative development funding." It is being supported by the UBS Optimus Foundation, the Credit Suisse Foundation and the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC). According to these sponsors, the initiative is expected to raise as much as CHF 1 billion in private capital, in order to achieve "measurable impact in developing countries". SECO is contributing CHF 19.5 million to the initiative, and the UBS Optimus Foundation CHF 5 million; the contributions of the other participants are not yet known.

SECO's rationale for the partnership is that the funding gap to meet the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030 is estimated at more than USD 2.5 trillion per year. SECO therefore concludes that "private sector investments in developing countries must be increased in order to bridge this funding gap". Blended financing comprising public and philanthropic funds are seen as an effective way of mobilising private financing, which otherwise would not find its way into the countries concerned. The SDG Impact Finance Initiative aims to raise CHF 100 million from public and philanthropic players by 2030, and those funds will then serve to unlock "up to CHF 1 billion in private capital towards the SDGs in developing countries."

Three objectives have been stated: (1) supporting "innovative financial solutions" for new "impact-investing tools" through grant and seed funding, these being investments which, besides a financial return, also aim to generate positive, measurable social and environmental impact (innovation window); (2) promoting impact investing by mobilising more private capital and strengthening underlying portfolio companies (product window); and (3) contributing to " improved framework conditions for impact investing in Switzerland " and promoting "the quality of impact measurement". To that end, the initiative will work closely with Swiss Sustainable Finance (the umbrella association of financial service providers for the promotion of sustainable financial management) and the State Secretariat for International Finance (SIF).

The launch of the initiative (SIFI) raises numerous questions, first regarding governance and management. An association was established, chaired by a business lawyer, and including one representative from each of the banking foundations that are participating in the SIFI. Neither SECO nor the SDC is represented on the board. It is therefore hard to see how the federal representatives will be able to promote the development priorities that are to be implemented thanks to SECO’s contribution (and in the future presumably also that of the SDC).

Yet another key question is that of defining impact and measurability. To date there has been no universally applicable definition of impact investing, and according to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the boundaries of what may be regarded as impact investing are fluid. To cite the Chair of the OECD-DAC (Development Assistance Committee), "the difficulty lies in defining and measuring this impact. The various countries and public and private organisations use different instruments for measuring different criteria. If the risk of impact washing is to be tackled, public authorities must undertake to lay down standards and monitor their observance." What is more, internationally comparable data and assessment tools are lacking.

The recourse to development cooperation funds (currently CHF 19.5 million from SECO) raises the fundamental question of the Federal Government's role and aims under this initiative; its declared aim "to raise" CHF 1 billion in private funding to finance the SDGs in developing countries presupposes that there are measures to lower the (real or perceived) risks to private investors (de-risking). Such measures may take the form of guarantees, covering first losses, technical assistance for underlying portfolio companies or bearing project preparation costs. These measures are all tantamount to subsidies, the implicit aim of which is to facilitate the preparation of a portfolio of bankable projects that must conform to the risk-return profiles (risk-adjusted return) expected by private and institutional investors. Is the purpose of international cooperation funds therefore to satisfy the growing appetite of investors or – on the contrary – to ensure that the intended and unintended development impacts of investments are measured, monitored and made public?

The question also arises as to the criteria that should apply to the planned investments. Because public donors have so far not laid down a "sustainability framework"[1] for private financing, there is the danger that, with the level of requirements varying so considerably from one investor to another, the ESG criteria (environment, social, governance) may be applied arbitrarily (SDG washing). Besides, there are no indications as to the sectors and countries for which blended financing is intended and the SDGs to which it is meant to contribute. Lastly, this type of public-private partnership raises a number of systemic issues relating to the financialisation of development; the key question that arises when a portion of international cooperation funding is diverted from its original purpose of sustainably funding public goods and services and used as a "lure" and a lever for private investments is the following: does this new use of public funds in fact conform to inclusive development as is being pursued in the 2030 Agenda (leave no one behind)? In other words: how well-suited are these public funds for truly aligning private investments with the goals of sustainable and inclusive development and poverty alleviation? What kind of development is being promoted by this financialization? To what extent can these investments in developing countries contribute to combating inequality, both regionally and between social groups?

The discussion has only just begun.

[1] By indiscriminately incorporating the ambivalent ESG approaches rather than clarifying them individually, the latest reform of the World Bank’s Environmental and Social Framework leaves the door wide open to the danger of SDG washing. See Securitization for Sustainability. Does it help achieve the Sustainable Development Goals? Heinrich Böll Stiftung, 2019, p. 17.

Share post now