Share post now

Article

Leapfrogging with solar

29.11.2025, Climate justice

Trump wants to curb China's growing power in the geopolitical struggle for technological leadership. But under the notorious climate change denier, the US is already lagging behind in key solar technology. China, on the other hand, is busy equipping Africa with solar panels – and thus the continent with the greatest need for electrification through renewables.

There is an enormous demand for reliable electricity on the African continent. A man displays a solar panel for sale in a shop in Abuja, Nigeria. © Keystone/AP/Olamikan Gbemiga

California's Governor Gavin Newsom was also among those who spoke at the COP30 in Belém. He deplored that fact that Trump was turning the USA into a footnote at the climate conference. Kenyan scholar and climate activist Mohammed Adow has told the BBC that the USA is committing an "act of self-sabotage", as that country will ultimately "miss out on the energy of the future" as a result.

While the USA sees itself in a technology race against China that it is desperate to win in every possible field, the game is already over when it comes to solar technology. Three quarters of all solar panels produced worldwide since 2010 have come from China, and that share has grown substantially over recent years. This has been possible because the Chinese leadership is pursuing the clear goal of decarbonising the country (in the medium term, coal-fired power generation was also expanded in parallel for a long time.). And this with technologies and equipment being produced in their own country.

The success of this strategy is a problem for those who, for ideological reasons, stand in principled opposition to industrial policy in general, not to mention "green" industrial policy in particular. Those circles are very strongly represented in Switzerland, including in business schools and economics faculties, the NZZ and SECO. They readily point to China's current overproduction. But overproduction is relative, when we consider the enormous unmet demand for affordable and reliable power: 800 million people, mainly in Africa, are still without electricity.

But something is beginning to stir in Africa – described as the "take-off in solar in Africa" by Ember, a non-profit think tank specialising in energy matters. Ember substantiates this with impressive figures, and China of course takes centre stage. The past two years have witnessed almost a tripling of solar panel imports from China (excluding South Africa). This increase was evident all across Africa. In the 12 months to June 2025, 20 countries set a new record for imports of solar modules. 25 countries imported appreciable amounts (more than 100 megawatts). In Sierra Leone, for example, the modules imported in one year can supply 61 per cent of the electricity output (2023).

Across huge swathes of Africa, wireless technologies have made it possible to leapfrog the stage that entailed the building of landline telephone infrastructure in the countries of the Global North. Solar energy holds the same leapfrogging potential. Instead of concentrating the production of vast amounts of energy at one central location, it allows power generation to be decentralised and located close to those who consume the power. The potential of solar energy for Africa's development would be so much greater if only its use did not depend on imports from China. The first green shoots of local solar panel manufacturing are now appearing in Egypt, Morocco, Nigeria and South Africa.

Research paper

How the oil lobby undermines the energy transition

27.10.2025, Climate justice

Switzerland's climate policy relies primarily on offsets abroad. How did this come about? The hidden answer is called Avenergy Suisse, as revealed by our investigation into its questionable practices.

When polluters shape climate policy: the oil industry campaigns against domestic climate measures while promoting offsetting abroad. Oil refinery in Cressier, near Neuchâtel (Switzerland). © REUTERS/Michael Buholzer

Over the past 20 years, Switzerland has deployed its climate policies in such a way as to attain its climate targets only partly through emission mitigation at home. This is so, inter alia, because it is doing remarkably little to decarbonise the transport sector, and new oil and gas-fuelled heating systems are still being installed in buildings. In the negotiations on the Paris Climate Agreement, Switzerland therefore made a strong case for pursuing its climate targets by continuing to purchase emission reductions from other countries and attributing them to its performance so as to embellish its own results.

How did Switzerland come to choose this carbon offsetting option, which it still pursues despite copious criticism? An Alliance Sud investigation uncovers the tools used by the oil lobby to decisively influence Switzerland's most crucial climate policy decisions so as to delay decarbonisation in Switzerland. Instead, the lobby advocates the purchase of emission certificates (International Transferred Mitigation Outcomes, ITMOs) abroad. It works to further the interests of international oil corporations, partly with funding from them.

The Swiss oil lobby is called Avenergy Suisse and is funded by its members, the importers of heating and motor fuels, some of which are subsidiaries of foreign oil corporations. Besides, heating fuel dealers are also represented by Swissoil, with the Swissoil manager, Ueli Bamert, doubling up as policy officer at Avenergy Suisse. Bamert is currently standing as candidate of the rights-wing SVP party for election to the Zurich City Council. The oil lobby acts mostly in lockstep with the car industry lobby and often also with the Swiss Homeowners' Association. Following a dispute with Economiesuisse (umbrella organisation for the Swiss business sector) over the CO2 Act, oil and car lobbies joined the Swiss Union of Crafts and Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises, which really represents the interests of SMEs, but is making an exception for oil corporations. Meanwhile, Avenergy Suisse has also resumed its membership of Economiesuisse.

How does the oil lobby procee? While there is no information about the funding of Avenergy Suisse or its members, their activities are visible enough so that one can form an idea of their tools and procedures.

Misleading arguments

On its website, Avenergy writes that while the carbon emissions generated in Switzerland are very limited, "Switzerland's overall emissions increase through the consumption of imported goods. It therefore makes sense to keep open all climate action options in Switzerland and abroad." In an interview with the daily newspaper Tages-Anzeiger in November 2021, the body in charge of foreign offsets, the KliK Foundation, also deployed the imported emissions argument. In 2017, the Federal Council had laid out its climate policy up to 2030, with carbon offsetting abroad being a fixed element, “in the knowledge that through their imports, citizens and industry again generate roughly the same amount of carbon emissions abroad as they do here at home. Switzerland therefore has a duty to cut carbon emissions abroad as well.” The fact that Switzerland's imported emissions surpass its domestic emissions is of course true, as is its duty to mitigate these grey emissions. Yet neither the Federal Council nor Avenergy has ever called for imported emissions to be offset. The only purpose ever served by offsets abroad has been to embellish Switzerland's performance in domestic emissions. After all, mitigating imported emissions does not fall under the Paris Agreement and is not viewed by many players as being incumbent on Switzerland. In the public consultation on the ordinance relating to the Climate and Innovation Act, Avenergy thus supported the submission by the Swiss Union of Crafts and Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises, which stated: "Indirect emissions are not part of Switzerland's climate policy." The argument that offsets abroad are undertaken because we import large amounts of emissions is misleading. It diverts attention from the fact that Switzerland is not even concerned about sufficiently mitigating its domestic emissions.

Council of States heeds the industry’s "request"

The fuel lobby's major success 20 years ago in introducing a "climate cent" (Klimarappen) as a voluntary measure on the part of Swiss industry, designed to pay for carbon offsetting abroad and thereby avoid a statutory CO2 levy, is well documented. The oil lobby itself proceeded to set up the foundation responsible for offsets and to supply its Board of Trustees members in the process. It is now the KliK Foundation. That was tantamount to deciding that, if at all, Switzerland would meet its obligations under the Kyoto Protocol only through carbon offsetting abroad. As a study later showed, the bulk of the carbon credits traded under the Kyoto Protocol were not worth the paper they were printed on.

The industry's major influence was evident not only 20 years ago, but to this day, it remains very well networked. According to the vested interests made public, numerous representatives of the car industry lobby, the Swiss Homeowners' Association and the Swiss Union of Crafts and Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises – including influential party and parliamentary group members – are sitting in Parliament. Up to the end of 2022, the current Federal Councillor Albert Rösti was President of Swissoil and a member of the National Council. Today he is the minister with responsibility for climate, energy and transport. Besides, Avenergy is being represented by the Farner public affairs agency, which, on its behalf, also leads the parliamentary group on hydrogen.

One anecdote from last year's deliberations on the CO2 Act in the Council of States illustrates just how great and obvious the industry’s influence on politics is. When Council of States member Hans Wicki tabled a last-minute proposal to replace the concept of "synthetic fuels" with that of "renewable fuels", he explained that it was a "request" from the "industry". After being informed by a colleague that the desired amendment would massively reduce the climate impact of the Act, the man submitting the proposal said that he was unable to make such an assessment but that he was merely saying that the industry had pointed out to him that the concept should be "corrected". The Council of States approved the amendment with a vote of 27 to 13, in line with the oil industry. The National Council then reversed that decision.

Yet another anecdote: During the latest review of the CO2 Act in Parliament, climate action was watered down so much that Switzerland was left more dependent on offsets abroad than the Federal Council had originally proposed. Thereafter, the industry verifiably lobbied the Federal Office for the Environment (FOEN) with a view to reducing its own level of carbon offsetting.

Avenergy and like-minded associations secure this influence also through targeted donations during federal elections. While the national political funding register for the recent 2023 elections tends to show the larger donations by the car industry lobby and the Houseowners' Association, there is also a cantonal register that shows evidence of Avenergy activity. Unlike the national register, that of the Canton of Freiburg also transparently records four-figure contributions. In 2023, Avenergy contributed 5000 francs to each candidate of the Liberals (FDP) and SVP to the Council of States. This suggests that it is also directly supporting candidates in other cantons. The national register, on the other hand, has so many possibilities for circumvention, that the absence of entries does not automatically mean that no contributions went to particular parties or candidates. The truth remains hidden.

Avenergy makes a mockery of climate justice

Avenergy spearheaded the no-campaign worth millions during the 2021 referendum against the revised CO2 Act. However, besides the official campaign by the oil lobby and its allies, there were also ancillary campaigns which at first glance looked less like the oil lobby, but which turned out to be just that. Initially, the "Liberal committee for an effective environment policy", which also opposed the Act, looked like a group of Young Liberals. However, the family business of campaign leader Alain Schwald, Schätzle AG, is owned by AVIA, which is a member of Avenergy. "IG Klimagerecht" also opposed the CO2 Act. This website argued that climate action was a global task to be done through international cooperation, but misused the concept of "climate justice" so as to call for a substantial foreign component in Switzerland's climate policy. IG defines justice in such a way that climate action should not entail any redistribution. In so doing, it omits to mention that the poorest people are the ones worst affected by the climate crisis, having contributed the least to it. Accordingly, part and parcel of climate justice is also redistribution in the form of compensation payments by the perpetrators. The cynical originator behind the site notice – again Avenergy Suisse, representing an oil industry that is fuelling the climate crisis through its business dealings worth billions.

Avenergy subsequently became more careful with slogans against climate and energy laws, but it is financial involvement continues. This is so not only at the national level, as shown by vote on cantonal climate legislation in Valais in November 2024. At the opponents' post-election party, the newspaper "Le Nouvelliste" ran into Avenergy's media spokesperson, who was thrilled at the outcome and at money well spent. Asked if Avenergy had helped to fund the campaign, he refused to make a statement, and asked the journalists not to reveal his presence at the party. Many votes on cantonal energy and climate laws have taken place in recent years, often with massive counter-campaigns by the SVP. In September 2025, the canton of Zürich voted on climate legislation – Avenergy's policy officer and Swissoil Managing Director, acting in his SVP party capacity, was prominent on the committee of the opposing campaign, which won the vote by wielding misleading arguments.

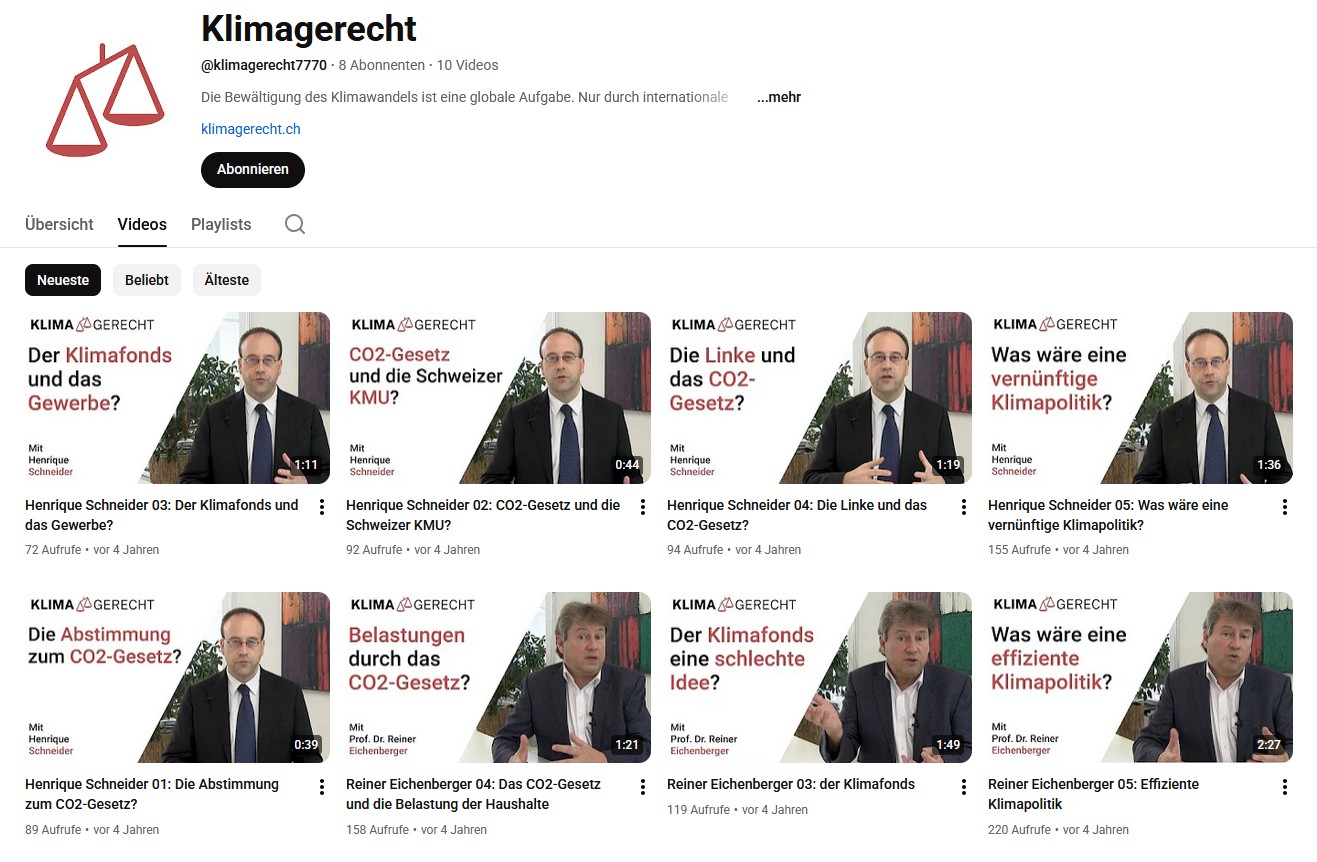

Fig.: The YouTube channel operated by "IG Klimagerecht" also has little to do with tackling the climate crisis in a globally equitable manner. During the 2021 referendum campaign, 10 short videos opposing the CO2 Act were uploaded. Along with the then Deputy Director of the Swiss Union of Small Businesses (SGV) Henrique Schneider, Freiburg University Professor Reiner Eichenberger was also roped in by Avenergy.

Image campaigns for fossil fuels

Avenergy can afford not just political campaigns but also invests in channels designed to incite the public to continue purchasing combustion engine vehicles and installing oil-based heating systems. On behalf of Avenergy Suisse, the Bertakomm agency manages seven social media platforms with video content, and a website with blog contributions. It takes turns questioning the phase-out of fossil fuels by 2050, discussing the costs of the energy transition without mentioning the costs of global warming, extolling the virtues of oil-fired heating, or arguing that a CO2 levy on thermal fuels makes no sense from the standpoint of the consumer and the industry. What attracts the most views, however, is a mini-series in which people at a petrol station asked, for example, whether they take the train or drive their cars when going on vacation, and why. Of course, the concept does not include asking the same question at a railway station.

In addition, Swissoil organises regular "information events" for the public in order to demonstrate that oil-fired heating is still permitted virtually everywhere and is to their advantage.

Conclusion: A targeted strategy against the energy transition

The oil industry is therefore militating very actively against domestic climate action – in part with misleading arguments and invariably with non-transparent spending – at the political level, against incentive measures, and in public, through one-sided information against the voluntary changeover to fossil-free technologies. It has managed to persuade a majority in Parliament to regard the purchase of ITMOs abroad as equivalent to emission mitigation at home, even though the scientific literature on carbon offset markets has been pointing out for years that ITMOs cannot be treated as emission mitigation units on a one-to-one basis, as they are highly error-prone.

The oil lobby will therefore bear some responsible if omissions in Switzerland do not diminish quickly enough. At the same time, through the foundation responsible for carbon offsetting, the industry prides itself as being part of the global solution to the climate crisis. While it urges the public in Switzerland to use combustion engine vehicles, it funds e-bikes in Ghana and e-busses in Bangkok. Its involvement in the carbon offset market is helping to keep emissions far too high in Switzerland and to perpetuate the dependence of Swiss citizens on fossil-based heating and motor fuels.

Share post now

Analytical paper

Carbon trading: helping or hindering global climate action?

05.11.2025, Climate justice

At the climate conference in Baku a year ago, the international community adopted new rules on the trade of Internationally Transferred Mitigation Outcomes (ITMOs) between countries. Some countries are hoping to attract investments, others are using ITMOs to achieve their nationally determined contributions. Taking the example of Switzerland, Alliance Sud and Fastenaktion question whether Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, which regulates ITMO trading, is really leading to more climate action.

A wrong turn or fast track to energy transition: Switzerland is offsetting CO2 emissions cheaply abroad and continuing as before with domestic transport and consumption. © KEYSTONE/Gian Ehrenzeller

Switzerland considers itself a pioneer under the Paris Agreement which, 10 years ago, was widely hailed as a breakthrough in international climate policy. The Swiss Confederation was the quickest to implement Article 6, under which countries may trade in ITMOs in order to achieve their climate goals: the first bilateral agreements have been concluded, first projects approved, and the first ITMOs have been bought. On paper, Switzerland can achieve its climate targets by purchasing ITMOs despite only a negligible decline in Swiss greenhouse gas emissions. In exchange, climate action projects are being implemented in the Global South – e.g., by selling efficient cooking stoves, and promoting e-buses and e-bikes; the resulting emission reductions are then attributed to Switzerland. What does this trade in ITMOs mean for global climate action? Criticism of carbon offset projects is often countered with the assertion that they are expressly contemplated in the Paris Agreement. This is true on the sole condition that, overall, the trade in ITMOs generates more, not less climate action.

The experts from Alliance Sud and Fastenaktion investigated and analysed just how far Switzerland meets this condition as a pioneer of the Article 6 mechanism and unearthed a surprising number of puzzle pieces relevant to answering this question.

Share post now

South Perspective

Africa – key continent for the energy transition

02.10.2025, Climate justice

It is now time to promote responsible mining practices that enable Africa to maximise the returns from its strategic reserves of transition minerals, secure better standards of living for its citizens, and mitigate negative social and environmental impacts. Emmanuel Mbolela

Who profits from coltan, the mineral that powers our future? The Rubaya mines are at the centre of the war between the M23 militia, Congo and Rwanda. © Eduardo Soteras Jalil / Panos Pictures

The world energy transition is deemed indispensable to the fight against global warming and the shaping of a sustainable energy future for coming generations. For about the past decade, the topic has been unavoidable in political and public debates in countries of the North and South. Africa figures in those debates as a continent that embodies the solution by virtue of its exceptional biodiversity, which leaves no doubt about its key role as a global carbon sink. Africa has been integral to these debates also by virtue of its subsoil, which holds deposits of the various transition minerals (copper, cobalt, lithium, nickel, coltan and tantalum) that the world needs for manufacturing electric vehicle batteries, storing renewable energies, and for the innovative technologies that are key to the global energy transition. According to the International Energy Agency, demand for these minerals will grow 4 to 6 times by 2040.

Yet there is still an open question regarding the fate of the continent that produces and supplies these strategic raw materials. Will Africa serve yet again as a mere cash cow, or will this energy transition process pave the way for its emergence?

Africa has always been at the heart of the major transformations that have led to the industrialisation of nations, and this at a very high cost.

History repeating itself

Let me recall that thanks to its population and natural resources, Africa has always been at the heart of the major transformations that have led to the industrialisation of nations, and this at a very high cost. One such cost was the slave trade, in which Africans were forcibly put on ships, transported under inhumane conditions, and sold in America to work on sugar or cotton plantations. Another example is rubber, which was used to make the inflatable tyres that revolutionised the entire automobile industry. Its extraction, however, left painful memories behind in the producing African countries. We will never forget the physical violence (severing of hands, kidnapping of women and children) meted out in the Congo by King Leopold II of Belgium to compel the people to extract more of this white gold, the sale of which served only to enrich the King himself and to develop his Kingdom of Belgium.

The industrial revolution of the 20th century was made possible thanks to the commodities supplied by Africa. Also worthy of mention is the uranium extracted in the south of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and used to manufacture the atomic bomb that helped to end the Second World War. Only very recently, in the development of modern-day information and communication technologies, Africa was again called upon to supply the raw materials, especially coltan, which is used in the manufacture of telephones and notebooks.

Paradoxically, Africa is at the bottom of the hierarchy. Its sons and daughters are being forced to become wanderers in search of an El Dorado. They are dying in the desert and at sea, under the complicit and culpable gaze of those who have the means to save them but refuse to do so under the pretext that they would be creating a pull factor.

Emmanuel Mbolela holds a Master's degree in Applied Economics, with a specialisation in “Nouveaux environnements économiques et entrepreneuriat éthique” [New Economic Environments and Ethical Entrepreneurship] from the University of Angers in France.

He is an advocate and defender of fundamental migrants’ rights and author of the book titled “Réfugié : Une odyssée africaine“ [Refugee: an African odyssey]. He is the founder of the “Association des réfugiés et des communautés migrantes” [Association of refugees and migrant communities], and initiator of the project to create a shelter that provides temporary and emergency accommodation for migrant women and their children.

Today, Africa is again being called upon. It is showing up as it has always done for every rendezvous with history that has marked the industrialisation of nations. And yet again, it is playing the role of a continent with the solution – this time serving as a carbon sink to counteract global warming, and as the supplier of raw materials indispensable to the energy transition.

Yet, while previous industrial revolutions have helped to develop Western countries and improve their people’s quality of life, Africa’s lot has been bloodshed and painful memories. One example is the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), which, for thirty years now has been witnessing a war of depopulation and repopulation in its eastern region, where gigantic transition mineral mines are located. Although the country does not possess a single weapons factory, this armed conflict has already claimed millions of lives and spawned hundreds of thousands of internally displaced people and refugees. The large-scale rape of women and children is legion and is being used as a weapon of war to drive people out of towns and villages, forcing them to abandon their lands which are then immediately captured for mineral mining.

On the back of exponential growth in the demand for these minerals, we are now witnessing predatory and illicit practices in their extraction: child labour is being used in mines, armed conflicts are being deliberately provoked, and agreements are being signed with no transparency whatsoever, not just by multinational corporations but also by governments. Let us take the example of the agreement signed in February 2024 between the European Union and Rwanda on the sale of critical raw materials. It was signed just as that country had invaded its neighbour the DRC, and in full awareness on the part of the EU that Rwanda possesses no mines for these metals and that the minerals it is putting up for sale on the international market are being plundered from the DRC.

Cobalt ore from the Shabara mines in the Congo, where thousands of people dig in the most adverse conditions in an area controlled by Glencore. © Pascal Maitre / Panos Pictures

A peace agreement between the DRC and Rwanda was just signed on 27 June in Washington, with the mediation of the Trump administration. This agreement was reached after negotiations between American and Congolese authorities on the exploitation of rare raw materials, and is in line with President Trump's philosophy of exchanging peace for strategic minerals. It is the businessman's administration – President Trump has stated his readiness to end Rwanda's aggression against its neighbour the DRC, provided the latter cooperates with the United States in exploiting its mineral resources. It is now clear that this agreement, so much vaunted by Donald Trump, is really nothing other than the opening of the doors to the United States, thereby granting it access to minerals indispensable to world technology.

Multinationals are motivated by profit maximisation. They are not interested either in creating stable employment or in sustainable extraction practices.

The inevitable outcome of such an agreement will be peace without food security and the outbreak of a conflict between the great powers on African soil. This is even more likely as the multinationals that would be coming to the Congo are motivated by profit maximisation and would accordingly extract and take the products away for processing in their respective countries. They are not interested either in creating stable employment or in sustainable extraction practices. We cannot rule out the possibility that this accord could eventually trigger a war on Congolese soil between the great powers, more specifically the European Union and the United States of America, risking a repeat of the situation that arose around 1997 in Congo Brazzaville. That country’s democratically elected government was overthrown because President Lissouba had signed oil mining agreements with American companies, to the detriment of French companies that had long been present there. Those companies lost no time in re-arming former President Sassou-Nguesso in order to overthrow Pascal Lissouba. The ensuing war claimed hundreds of thousands of lives and spawned hundreds of thousands of internally displaced persons and refugees, and was subsequently described as an ethnic war.

Besides the aforementioned agreements, there was also the railway construction megaproject initiated by the United States and supported by the EU, designed to link the Democratic Republic of the Congo with Zambia, and to end in Angola’s Port of Lobito. It was inaugurated in Angola by former US President Joe Biden in his final days in office, and is intended to shorten the time needed to transport raw materials. Such a project takes us back to those launched during the colonial era, when roads and railways were built not to open up and develop colonies, but to link mineral mining areas or regions with the seas and oceans for easier transportation of raw materials to the metropolis.

Such reforms must end predatory exploitation, so that these minerals no longer constitute a curse, but instead bring happiness and a zest for life to the population.

Young Africans, who watch day by day as thousands of containers laden with these riches leave the continent for distant places (Europe, United States, Canada, China…), are calling for thoroughgoing reforms. Such reforms must end predatory exploitation, so that these minerals no longer constitute a curse, but instead bring them happiness and a zest for life.

In particular, the benefits derived from strategic reserves of transition minerals should be maximised for the good of the extracting countries so as to improve their citizens’ standard of living and mitigate the negative impacts of mineral mining.

Holding companies accountable

To this end, it is high time to activate and encourage the rigorous and bold implementation of the various international policies that have been lying dormant in drawers. These include the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises on Responsible Business Conduct, and the guiding principles of the UN Secretary-General's Panel on Critical Energy Transition Minerals.

If the energy transition is to be fair and equitable, then it would be fair to apply the polluter pays principle, not that of the polluted pays.

Support for undertakings like the Responsible Business Initiative in Switzerland goes without saying. The success of such initiatives depends, among other things, on raising public awareness and adequately informing citizens about the human tragedies and the environmental degradation being caused by the mining industry in Africa. Such actions could support the ongoing and unrelenting struggle of civil society across African countries to advocate for greater societal and environmental responsibility on the part of companies operating in the industry.

These multinational corporations are in a position of strength, especially when it comes to the conclusion of mining contracts – often opaque and unknown to local communities. They use their position to bypass the rights of citizens and the fundamental rules of mining. They conduct their mining activities in a manner that overlooks the elementary rules of public health and fails to respect the rights of the local people. They are therefore the root cause of the air pollution and toxic water contamination that are giving rise to pathologies often unknown to the population, but which are lethal and are helping to exacerbate the public health crisis.

African societies are still waiting for countries in the North to acknowledge the role being played by Africa. This role deserves climate funding and compensation for the part that African peoples are being required to play in environmental preservation. If the energy transition is to be fair and equitable, then it would be fair to apply the polluter pays principle, not that of the polluted pays.

Share post now

global

The Alliance Sud magazine analyses and comments on Switzerland's foreign and development policies. "global" is published four times a year (in german and french) and can be subscribed to free of charge.

Article

World Bank reform: Back to the future?

29.06.2025, Financing for development, Climate justice

At the UN conference in Seville, the future direction of international financial institutions is also at the centre of discussions. However, the development of the World Bank remains far from the urgently needed revolution.

The idea of attracting private capital on a large scale to finance roads, hospitals and other urgently needed infrastructure projects in the poorest countries also proved to be an illusion at the World Bank. © Shutterstock

In 2015, the World Bank launched a new strategy and vision – the “Forward Look: A Vision for the World Bank Group in 2030”. This was the birth of the Maximize Finance for Development approach, which aimed to massively increase private finance for development through sectoral and policy reforms, as well as the use of guarantees and various de-risking instruments. As a result, the slogan “from billions to trillions” became a much-repeated mantra in the broader development community. Fast forward to 2023 – the World Bank initiated a strategy process termed the “Evolution Roadmap”, which is supposed to make it better equipped to address modern development challenges and to renew its credibility. While the Evolution Roadmap changes the World Bank’s mandate and mission to include major global challenges, most notably climate change, operationally and financially, it is more a deepening and a continuation of the Maximize Finance for Development Approach (despite the fact that the “billions to trillions” slogan has in the meantime been debunked as a myth even by notable World Bank economists).

The (silly) dream goes on

Indeed, ten years after the launch of the slogan “from billions to trillions” – “well-meaning but silly” according to the CEO of the Private Infrastructure Development Group (PIDG), Philippe Valuhu, recently quoted by the FT, progress in finding private finance to fill the ever-growing funding gap (4,000 billion a year for the SDGs not counting climate financing needs) – has been very disappointing. The basic idea to use public funding to attract large amounts of private money, particularly from institutional investors did not materialize. The (over-) simplistic hope was that pension funds and insurance companies in rich countries would line up to finance roads, hospitals and other basic infrastructure sorely needed in developing countries.

Originally, when the slogan “from billions to trillions” was launched, the assumption was that every public dollar could leverage two or more private-sector dollars. Such a “leverage ratio” is only achieved in rare cases. A recent ODI study shows that “blended concessional finance” – i. e. public capital (mainly provided by MDBs) at below-market rates – attracted, in 2021, for every dollar, some 59 cents of private co-financing in Sub-Saharan Africa – the region where needs are greatest – and 70 cents elsewhere. Multilateral development banks (MDBs) and development finance institutions (DFIs) have been and remain at the forefront of these “mobilization” efforts. By 2023, they together succeeded in mobilizing some 88 billion USD of private financing for middle-income and low-income countries (MICs and LICs), out of which 51 billion were mobilized by the World Bank Group (including its private sector arms IFC and MIGA), representing around 60% of the total amount of private financing mobilized. However, only 20 billion USD were mobilized for sub-Saharan Africa and only half of this reached the poorest countries (LICs). By way of comparison, the region received USD 62 billion in aid in the same year. Furthermore, more than 50% of these private funds went to just two sectors: banking and business services, and energy. By comparison, education and health and population together received less than 1%.

While the evidence is obviously disappointing, the amount of financing that MDBs should be able to “crowd-in” for development projects has become an idée fixe for donors and other stakeholders. So, the dream goes on, and the level of ambition has been raised considerably under the Evolution Roadmap. Although the WB's current president, Ajay Banga, has admitted that the “billions to trillions” formula is unrealistic, and its chief economist, Indermit Gill, has called it a “fantasy”, the Bank is experimenting with new and increasingly sophisticated models, including the bundling of loans into financial products that are then sold to private investors – a practice known as securitization, with the aim of freeing up capital to issue more loans.

New instruments are constantly being developed and praised for their potential to attract private capital: the idea is to extend the use of risk-sharing instruments such as guarantees, new investment vehicles and insurance solutions to mobilize private capital. The World Bank's most recent products are “outcome bonds”, aiming at mobilizing funding from private investors for projects in developing economies, by transferring performance risks to investors who are then rewarded if the underlying activities are successful.

Is climate finance being privatized?

Under the Evolution Roadmap, the World Bank has changed its vision to add “on a liveable planet” to its existing twin goals of eradicating extreme poverty and boosting shared prosperity. In line with this addition, it has positioned itself as a key player in achieving the new climate finance target agreed to at the COP29 in Baku. According to a statement released before the conference, the “World Bank Group is by far the largest provider of climate finance to developing countries”. In 2024, it reportedly delivered 42.6 billion in climate finance (amounting to 44% of its total lending). While there are also significant problems with regards to accounting and transparency of WB climate finance, this article focuses primarily on climate finance as part the broader privatisation agenda pursued by the WB.

As the World increasingly looks to multilateral development banks as providers of climate finance, the focus shifts away from much-needed public finance solutions. A recent analysis by the Bretton Woods Project highlights how the World Banks climate finance is deeply embedded in its broader privatisation agenda. This is also particularly visible in its development policy financing (DPF), which in 2023 accounted for 22% of IDA and IBRDs (the WB organisations in charge of providing loans and grants to poor and middle-income countries) climate finance. DPF is a form of non-earmarked, fungible budget support that is linked to concrete policy reforms (prior actions). Most of the prior actions required were linked to market-based reforms, including de-risking measures for private investment or the removal of consumer subsidies on fossil fuels (which are found to have a particularly punitive impact on the poorest segments of populations).

Furthermore, the majority of MDB climate finance comes in the form of loans, rather than grants, thus increasing the debt burden of already highly indebted countries. In fact, in 2023, loans accounted for 89.9% of IBRD and IDA climate finance (the two WB organisations that account for the largest share of WB climate finance). The fact that these loans – which by definition have to be paid back with interest – are also attributable to the climate finance of WB member states also stands in sharp contradiction to the “polluter pays” principle.

Evolution reversed

The WB Evolution Roadmap is hence far from a revolution in terms of its private sector agenda but could be classified as “more of the same, including climate”. However, the expansion of climate finance is now being severely challenged by the new US administration. While recently reaffirming its commitment to the WB (and IMF), Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent called for a return to its core mandates and reforms of “expansive” programs. The Bank should support “job-rich, private-sector-led economic growth”, and move away from its social or climate programs. Mr. Bessent stressed that the Bank should be “technology neutral” and prioritize the affordability of energy investments. In most cases, this means “investing in the production of gas and other fossil fuels”. In order not to offend the new US administration, the Bank has become rather silent on its climate agenda and following a request by the US has recently decided to end its moratorium on nuclear energy and a vote on reintroducing financing for the exploration and extraction of gas should follow in the near future. Whether the US administration will be able to force the WB to reverse the expansion of its vision and mandate and to move away from its “Paris alignment” commitment or whether the European chairs will be in any position to oppose such disastrous decisions, as well as what role Switzerland will play, remains to be seen.

Revolution postponed

As the World’s development community gathers in Sevilla to discuss the future of development finance, some of the sticking points may become clearer. Once more the “Sevilla compromise” highlights the enormous financing gap of 4 trillion USD needed to reach the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030. While it acknowledges that “private investment in sustainable development has not reached expectations, nor has it adequately prioritized sustainable development impact”, the document goes on to outline a broad set of measures aimed at “increasing the mobilization of private finance from public sources by strengthening the use of risk-sharing and blended finance instruments”, with MDBs playing a key role in this agenda. While the frantic search for new instruments and ways to make development and climate projects “bankable” and thus more appealing for private investors continues, the debt crisis takes on speed and the role of the public sector as a provider of much-needed development and climate finance is further weakened.

According to the World Bank chief economist Indermit “since 2022, foreign private creditors have extracted nearly $141 billion more in debt-service payments from public-sector borrowers in developing economies than they have disbursed in new financing.” Today, several African countries spent more than half of their resources on debt repayment and Indermit event admits that some countries simply use World Bank loans (which have a longer maturity rate) to pay back their private creditors, thereby diverting scarce resources “away from areas critical for long-term growth and development, such as health and education”.

While private capital certainly can and should play a role in sustainable development and climate finance, it is time to abandon simplistic solutions and to address the root causes of current multiple crisis. This would include a much-needed reform of the WBs governance structure to give countries in the Global South more decision-making power, as well as broad-based debt restructuring and cancellations, as well as investments in domestic resource mobilisation and a fairer global tax system with the aim to combat rising inequalities world-wide. It does not look like Sevilla will be the place, where the much-needed revolution starts, but the fight goes on.

Share post now

Sustainable finance

For financial flows without environmental degradation abroad

20.03.2025, Climate justice, Finance and tax policy

The Swiss financial centre has demonstrated that it will not voluntarily give up business involving environmental degradation abroad. The Financial Centre Initiative aims to amend the Constitution to include a ban on new investments in coal, oil and gas by Swiss financial market players.

The rainforest in Pará, Brazil, is climatically significant and indigenous land. But it is increasingly being destroyed by deforestation, mines and infrastructure projects - mostly involved are Swiss financial players.

© Lalo de Almeida / Panos Pictures

Felling rainforests helps drive environmental degradation and global warming. That is common knowledge. Besides, illegal slash-and-burn practices often curtail the land rights of indigenous communities and also violate their human rights. Switzerland's banking major UBS knows this. Yet it invests in large Brazilian agribusinesses that are involved in illegal forest clearances in the Amazon, as revealed some time ago by the Society for Threatened Peoples.

Each year, Swiss banks and insurance companies fund or insure billions worth of business operations that degrade the environment and drive global warming. According to a McKinsey study, the Swiss financial centre is responsible for as much as 18 times the amount of carbon emissions generated in Switzerland. Already ten years ago, the international community enshrined in Article 2.1(c) of the Paris Climate Agreement the key role of the financial system in addressing the climate crisis. It laid out the goal of "making finance flows consistent with a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development." Switzerland has ratified the Agreement and is bound by international law to contribute to achieving this goal. Approved by an overwhelming majority of Swiss voters, the Climate Protection Act further requires the federal government to ensure the climate-friendly orientation of financial flows. But implementation is not going smoothly.

"Voluntary" assumes that there is a will

The Federal Council is relying on voluntary and self-regulatory implementation measures by the finance industry, and rejects any additional state regulation. It did, however, support a motion by National Councillor Gerhard Andrey (Greens) which provided for more stringent actions, should the measures in place prove ineffective by 2028. The Parliament rejected the motion in the spring of 2024, however, and saw no need for further action.

We are now seeing that voluntary promises by these banks are not enough.

By January 2025 at the latest, it became clear why the financial sector's voluntary measures and promises were worth so little. The six largest American banks and the world's biggest asset manager BlackRock reneged on the climate promises they had made just four years earlier. Speaking on Western Switzerland television RTS, Professor Florian Egli of the Technical University of Munich said: "We are now seeing that voluntary promises by these banks are not enough. They have reneged on their promises." The UBS, too, is considering withdrawing from the Net Zero Banking Alliance, in which, since 2021, numerous banks had committed to a net zero target by 2050. The banks therefore want to continue funding environmental degradation, if it increases their profits.

The Financial Centre Initiative is needed

Anyone relying on voluntary measures is exposing itself to the whims of the financial sector, which is obviously guided not by climate science but by easy money and political winds. This is no way to combat the climate crisis. The International Energy Agency has long made clear in its Net Zero Roadmap that promoting new fossil fuel extraction is not compatible with meeting the Paris climate goals.

This prompted Climate Alliance Switzerland to launch the "Financial Centre Initiative" in late 2024, jointly with the WWF, Greenpeace and politicians from all the federal parties except the right-wing SVP. It is intended to ensure that no one else operating out of Switzerland finances environmental degradation and global warming. Should the Government and Parliament continue to sit on their hands, the electorate has the power to amend the Constitution to prohibit Switzerland's financial sector from funding or underwriting any additional extraction of coal, oil or gas. The same rules would then govern all players.

Alliance Sud supports the popular initiative in order that Switzerland can finally activate its greatest lever to enhance worldwide climate protection and fully implement the Paris Agreement.

Federal Popular Initiative 'For a sustainable and future-oriented Swiss financial centre (Financial Centre Initiative)’

The initiative aims for:

- the environmentally sustainable orientation of the financial centre, with financial market players aligning their business activities abroad with international climate and environmental goals. Consideration is being given to binding transition plans to be implemented by the companies concerned.

- a prohibition on the funding or underwriting of new fossil fuel extraction projects or the expansion of existing ones.

Alliance Sud supports the initiative because:

- Switzerland is not sufficiently implementing the Paris Climate Agreement through self-regulation by the financial sector.

- the financial centre bears the greatest climate responsibility of all players under Swiss influence. It represents Switzerland's most important lever for helping to achieve worldwide climate protection.

Share post now

global

The Alliance Sud magazine analyses and comments on Switzerland's foreign and development policies. "global" is published four times a year (in german and french) and can be subscribed to free of charge.

Climate policy

Trade in carbon certificates – more apparent than real?

03.12.2024, Climate justice

Whether in regard to the CO2 Act or the new austerity programme: Swiss policymakers are relying increasingly on carbon certificates from abroad to meet their own climate target by 2030. Yet the plan could fail – the first programmes are already showing serious shortcomings. An analysis by Delia Berner

Old buses and ubiquitous face masks: Bangkok suffers from exhaust fumes, but do e-buses financed by Switzerland really help in Thailand? © Benson Truong / Shutterstock

In January 2024, Switzerland captured the world's attention – at least in the specialised world of the carbon markets. This was because, for the very first time, carbon emission reductions had been transferred in the form of certificates from one country to another under the new market mechanism in the Paris Climate Agreement. More specifically, Thailand had introduced electric buses in Bangkok and had reduced carbon emissions by around 2000 tonnes in the first year. Switzerland bought this reduction in order to count it towards its own climate target.

Let us take a step back: Switzerland plans, by 2030, to save more than 30 million tonnes of CO2 abroad rather than in Switzerland. The first bilateral agreements in that regard were concluded in the autumn of 2020, and their number has now surpassed a dozen. Several other projects are being developed, ranging from biogas facilities and efficient cooking stoves in the poorest countries, to climate-friendly cooling systems, and also to energy efficiency in buildings and industry. So far, only two programmes have been approved for attribution towards Switzerland's climate target. And the 2000 tonnes of CO2 savings from Thailand were in fact the first certificates to be traded. This means that much remains to be done by 2030 if there is to be a sufficient number of certificates available for purchase by Switzerland.

The first project could fail...

After inspecting case documents under the Freedom of Information Act, the "Beobachter" newspaper has now revealed that the very first programme in Bangkok is at risk of failing to generate any further certificates. Already a year ago, allegations began reaching the Federal Office for the Environment (FOEN) to the effect that the e-bus manufacturing company was violating national labour law and the right to the freedom of association enshrined in human rights law. Although a provisional agreement was reached a year ago, new allegations apparently surfaced this year, which the FOEN must now investigate. This is so because Switzerland cannot approve certificates if human rights violations were entailed in generating them. The FOEN was quoted in the "Beobachter" to the effect that it "can and will" suspend further issuance of certificates if the allegations are substantiated. Extensive investigation by the "Republik" magazine has brought yet more allegations to light. Supposedly, Switzerland was even implicated in an economic crime in Thailand by fuelling a 10-billion-franc stock market bubble and ignoring warnings.

The second approved project, too, will generate fewer certificates than promised. A new research by Alliance Sud into the cooking stove project in Ghana reveals that its planning entailed over-estimating emission reductions by as much as 1.4 million tonnes.

It is now already clear that, in general, foreign offsets are no cheaper and certainly no easier to implement than climate protection measures in Switzerland. The latter will have to be introduced sooner or later anyway in order to achieve the net zero target in Switzerland.

More than growing pains

The first projects illustrate the difficulties being encountered in ensuring that a project effectively reduces carbon emissions by a particular amount and is also cost-effective. Doubts surrounding reductions have been the reason why many offset projects have made the headlines in recent years. Cost effectiveness is crucial, as the majority of the certificates are paid for by the Swiss public through a tax on fuel. To verify these two things, the FOEN would need to examine the projects' financial plans. It would have to be persuaded, for example, that project costs include no disproportionate margins or profits, but that as much money as possible is being invested in climate protection or sustainable development, with the involvement of the concerned population groups in the partner country.

Yet the flaws of the Swiss system of foreign offsets are becoming apparent here. Because the certificates are not bought by the Confederation but by the Foundation for Climate Protection and Carbon Offset, Klik, which converts the proceeds from the fuel tax into certificates, the "commercial details" are not revealed to the public. What this means is that no one knows the cost of saving a tonne of carbon emissions by using e-buses in Bangkok, or the overall amount of money being invested in the cooking stove project in Ghana – let alone what the yields accruing to private market participants look like. Moreover, in the case of the aforementioned project in Ghana, extensive passages were redacted in the project documentation that was published. The transparency is even worse than in the case of serious standards in the voluntary carbon market.

Twofold need for action

These challenges go beyond mere teething problems and reveal a twofold need for action by Swiss lawmakers. First, the lack of transparency regarding project-related financial information in the ordinance on the CO2 Act must be remedied. The ordinance is currently being aligned with the latest revision of the Act. Second, the image of foreign offsets as a cheaper and simpler path to climate protection must be corrected. Switzerland must move ahead with climate protection within its borders and again achieve climate goals after 2030 without carbon offsets. Alliance Sud calls on the Federal Council to incorporate this into the CO2 Act after 2030.

Share post now

Private climate finance

The limits of the magic solution

05.12.2024, Financing for development, Climate justice

Many people favour greater use of private funding to cover current and future contributions from the countries in the North to those in the South in their fight against climate change. A stocktake by Laurent Matile

Correcting inflated expectations: An initiative launched by Barbados' Prime Minister Mia Mottley to promote climate finance for developing countries has scaled back its demands on the private sector. © Keystone / AFP / Brendan Smialowski

"The numbers that are thrown around about the potential of green capital mobilization are illusory. [...] There is a lot of piffle in this area." These were some of the remarks made by Lawrence H. Summers, former US Treasury Secretary and President Emeritus of Harvard University, in wrapping up a panel discussion in Washington D.C. last October.1

At COP29 in Baku, which ended on 24 November, a new climate financing goal was agreed at the last minute: developed countries have pledged to triple funding, from the previous target of USD 100 billion per year to USD 300 billion per year by 2035. This is far too little in view of the needs of developing countries, which are estimated to total USD 2,400 billion a year. In a nebulous formula, it was further agreed to ‘secure the efforts of all actors’ to increase funding for developing countries, from public and private sources, to 1.3 trillion dollars a year by 2035.

Despite not being central to the COP29 agenda, mobilising private climate finance is still considered the silver bullet by many public and private players. The definition of "climate finance" does not in fact specify what portion must be covered by public and/or private funding. This vagueness has spawned much uncertainty as to the source of the funds being allocated to climate, and allows governments ample leeway in meeting their commitments. And there is great temptation to use private funds to fill the public funding gap.

The fact is that since the conclusion of the Paris climate agreement in 2015, many public and private players – the ones Lawrence Summers has in mind – have stepped up their efforts to advocate for the design of "innovative financial instruments" that benefit from public subsidies and invariably pursue the same aim: that of de-risking in order to "catalyse" private investments, whether for the climate or for sustainable development. And this credo is not about to disappear. In the back of their minds, numerous delegations, including Switzerland, are thinking that whatever the final amount owed by each developed country, it will be possible to secure a substantial part of it by "mobilising private capital".

Let’s take stock

Let us consider for a moment the current state of climate finance in developing countries. The latest OECD2 figures show that:

- Eighty per cent (80%) of the total USD 115.9 billion in climate finance from industrialised countries (in 2022) came from public funds (bilateral and multilateral attributable to developed countries).

- Only some 20% comprises private funds mobilised using public funds. After several years of stagnation, the amount rose from USD 14.4 billion in 2021 to USD 21.9 billion in 2022, or by 52%. By way of comparison, total financing mobilised for sustainable development also rose significantly in 2022, by 27% (from USD 48 billion in 2021 to USD 61 billion).

- Climate-related export credits remain negligible and volatile in volume terms, and their share of the total has therefore remained low.

- The bulk of private financing (68%) continued to be mobilised in middle-income countries (MICs) and was concentrated in a limited number of developing countries, and allocated to a limited number of major infrastructure projects. A mere 3% was allocated to low-income countries (LICs).

- The lion’s share of private finance has gone to emission reduction (84%). Private finance for adaptation is just 16%, even though that amount, too, has increased – from USD 0.4 billion in 2016 to USD 3.5 billion in 2022; again, this funding, too, can be attributed to a small number of large-scale projects.

- Almost half the private finance mobilised is invested in the energy sector, and to a lesser extent, in the financial and industrial sectors, including mining.

The OECD recalls (time and again) that "a number of challenges may affect the potential to mobilise private finance" to combat climate change in developing countries. These include the general environment that may be enabling (or not) for investment in beneficiary countries, the fact that many climate projects are not profitable enough to attract large-scale private investment; or, the fact that individual projects are often too small to obtain significant commercial funding.

A credo nevertheless on the wane

Few ideas seem as hackneyed as the hope that a few billion dollars in public funds will be able to mobilise trillions in private investment for sustainable development and climate protection. This credo is increasingly being challenged, and not just by non-governmental organisations.

The Bridgetown Initiative 3.0, for example, has reassessed its expectations regarding the mobilisation of the private sector. Launched in 2022 by Mia Mottley, the charismatic Prime Minister of Barbados, the third version of this initiative was published in late September. It aims to rethink the global financial system in order to reduce debt and improve access to climate finance for developing countries. While Bridgetown 2.0 called for over USD 1.5 trillion per year to be mobilised from the private sector for a green and just transition, version 3.0 has scaled back the amount being requested to "at least USD 500 billion".

In the light of the outcomes in terms of the volumes and characteristics of private finance mobilised to date, a number of conclusions can be drawn:

- First, private climate finance, whether or not mobilised by means of public funds, focuses primarily on emission reduction projects in middle-income countries, mainly in the energy sector considering the profitability of these large projects, while private funds for adaptation in low-income countries remain marginal.

- Second, the stagnation of global private climate finance casts doubts over the potential for private resources to grow as rapidly and as extensively as their advocates had hoped.

- Public funding must therefore remain central to efforts to help developing countries mitigate emissions and, above all, adapt to climate change and remedy unavoidable loss and damage. To that end, "new and additional" funding must be provided, separate and apart from development cooperation budgets.

Position of Alliance Sud

First, Alliance Sud is calling for most of Switzerland's "fair share" to international climate finance to be provided through public funding – with a balance between funds allocated to mitigation and those allocated to adaptation. Second, the call is also made for private funding mobilised through public instruments to be counted towards Switzerland’s climate finance only if its positive impact on people in the Global South can be duly demonstrated.

1 CGD Annual Meetings Events: Bretton Woods at 80: Priorities for the Next Decade, Washington D.C., October 2024.

2 Climate Finance Provided and Mobilised by Developed Countries in 2013-2022, OECD 2024.

Share post now

global

The Alliance Sud magazine analyses and comments on Switzerland's foreign and development policies. "global" is published four times a year (in german and french) and can be subscribed to free of charge.

Trade and climate

Carbon border taxes must not penalise poor countries

03.12.2024, Climate justice, Trade and investments

Imports of the most polluting products are to be taxed under the European Union's Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM). No exemption is being contemplated for the poorest countries, even though they will be severely affected. Should Switzerland ever adopt this measure, it would have to make sure to put this right.

One of the world's largest uranium ore mines closed in Akokan, Niger. However, more are planned in the crisis-ridden north and are economically significant. © Keystone / AFP / Olympia de Maismont

The European Union (EU) takes its climate commitments seriously. In 2019, it launched the European Green Deal, designed to cut CO2 emissions by 55% by 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality by 2050. The programme encompasses a number of internal and external policy measures, including the European Union Deforestation Regulation (EUDR, see global #92). Another key European trade policy project is the CBAM, or Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism. Its purpose is to make importing industries subject to the same rules as polluting European enterprises. The latter must observe a cap on emissions, which, by the way, they can trade on the "carbon market" in order to comply with the limits set. These measures are designed to render investment in clean energy in Europe cheaper and more attractive. "The CBAM will encourage global industry to adopt greener technologies," European Commissioner for Economic Affairs Paolo Gentiloni has said.

Avoiding carbon leakages

Brussels adopted the CBAM in order to prevent production from moving to countries where the price of carbon is lower than in the EU, or even zero (known as "carbon leakages"), or to shield European producers from unfair competition. Under this mechanism, imports of particularly polluting products will be taxed at the border, starting with iron and steel, cement, fertilisers, aluminium, hydrogen and electricity. It took effect in the EU on 1 October 2023 and is being implemented in successive phases; the mechanism will be fully deployed as of 2026. Starting in 2031, it is expected to cover all imports.

Poorer countries affected

The fundamental question is whether the measure is effective. The EU is optimistic. It estimates that its emissions will decline by 13.8% by 2030, while those of the rest of the world will be down by 0.3% compared with 1990. But the approach elicits sharp criticism from the countries of the Global South, which assert that it is negatively impacting their development. Others criticise it for failing to provide a general waiver, at least for the poorest countries. Moreover, UN Trade and Development (UNCTAD) has calculated that the impact on climate is expected to be minimal: the CBAM will reduce global CO2 emissions by a mere 0.1%, while EU emissions will diminish by 0.9%. It is nonetheless expected to boost the revenue accruing to developed countries by USD 2.5 billion while reducing the revenue going to developing countries by USD 5.9 billion.

In 2022, ministers from Brazil, South Africa, India and China called for discriminatory measures such as carbon taxes at borders to be avoided. The countries most affected by this mechanism are the emerging countries that are the leading exporters of steel and aluminium to Europe, namely, Russia, Turkey, China, India, South Africa and the United Arab Emirates. But Least Developed Countries (LDCs, a category created by the United Nations) such as Mozambique (aluminium) and Niger (uranium ore) will also be impacted. The welfare losses to developing countries like Ukraine, Egypt, Mozambique and Turkey are put at EUR 1–5 billion, a substantial amount considering their gross domestic product (GDP).

An exemption for LDCs

Let us take Africa, which is home to 33 of the 46 LDCs. A recent study by the London School of Economics concludes that if the CBAM were applied to all imports, Africa's GDP would contract by 1.12% or EUR 25 billion. Aluminium exports would decline by 13.9%, iron and steel by 8.2%, fertilisers by 3.9%, and cement by 3.1%. So, should the baby be thrown out with the bathwater and the CBAM declared to be anti-development? Probably not. The Belgian NGO 11.11.11. proposes that the least developed countries be exempted from this mechanism, at least initially, under WTO rules; or that they be taxed less than the others. When the CBAM was being discussed in Brussels, this possibility was considered then jettisoned by the Parliament, as the EU opted to secure more revenue. UN Trade and Development suggests returning the revenue from the mechanism to the LDCs to fund their climate transition. The EU is expected to garner revenue of EUR 2.1 billion, which could be channelled multilaterally via the Green Climate Fund, itself currently underfunded.

No CBAM in Switzerland for the time being

For now, there is nothing of the kind in Switzerland. Goods originating in Switzerland and exported to the EU are currently exempt from the CBAM by virtue of the Emissions Trading System (ETS), and the Federal Council has opted not to introduce any such mechanism for products being imported into Switzerland. The ETS represents the maximum amount of emissions available to industries in a particular economic sector. Each participant is allocated a certain quantity of emission rights. If their emissions remain below this limit, they may sell their rights. If they exceed the limit, they may purchase rights.

A parliamentary initiative was submitted to the National Council in March 2021 calling on Switzerland to amend the CO2 Act to include a border carbon adjustment mechanism, taking account of developments in the EU. Currently, that parliamentary initiative is still being discussed in the committees. The CBAM could be an effective trade measure for reducing imported CO2 emissions. But should Switzerland ever adopt it, it would have to make sure not to penalise the poorest countries, instead granting them exemptions, and returning a substantial part of the accrued revenue to assist them in making the energy transition.

International trade accounts for 27% of emissions

Greenhouse gas emissions generated by the production and transport of exported and imported goods and services account for 27% of global greenhouse gas emissions. According to the OECD, these emissions come from seven economic sectors, namely, mining and energy production, textiles and leather, non-metallic chemicals and mining products, base metals, electronic and electrical products, machinery, vehicles and semiconductors.

Action is undoubtedly needed on both the trade and production fronts – on the production front, for example, by promoting green technologies, technology transfer and climate finance. On the trade side, through other measures such as the CBAM, though without penalising poor countries. The latter must be assisted in managing their ecological transition and adapting to the new standards.

Share post now

global

The Alliance Sud magazine analyses and comments on Switzerland's foreign and development policies. "global" is published four times a year (in german and french) and can be subscribed to free of charge.

Swiss Environment Minister at COP29

Grandma's house and poor Switzerland

29.11.2024, Climate justice

The UN Climate Change Conference COP29 has come to an end, while the climate crisis is destroying the livelihoods of millions of people. While delegates from the Global South criticise the inadequate climate financing, Swiss Environment Minister Albert Rösti shirks Switzerland's responsibility, citing budget restrictions and the mobilisation of private funds. This is an affront, writes Andreas Missbach.

Palm trees uprooted by Hurricane Beryl in St Patrick, Grenada, in July 2024. Houses and entire areas were destroyed throughout the Caribbean. © Keystone / AP Photo / Haron Forteau

On 17 July 2024, Simon Stiell stood in a damaged house on his native island of Carriacou and said: ‘Today, I'm standing in the living room of my neighbour’s house. My own grandmother's house down the street has been destroyed.’ That was the work of Hurricane Beryl, which had swept over Grenada and many other countries. He also said: ‘Standing here, it's impossible not to recognise the vital importance of delivering climate finance, funding loss and damage, and investing massively in building resilience, particularly for the most vulnerable.’

Simon Stiell is Executive Secretary of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change and, as such, responsible for the 29th Conference of the Parties to this Convention in Baku. On 22 November 2024, Swiss Environment Minister Albert Rösti stood in front of a television camera there and said: ‘We have budget restrictions, we have an austerity programme ...’. What is wrong in Bern is an affront in Baku. An affront to people in countries like Grenada, and it is an affront to the delegates from the Global South. According to a recent study by the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, the emissions already caused by industrialised countries mean that these countries will have a 20 to 30-per cent weaker economic performance in 2049, than without climate change.

Official Switzerland, on the other hand, has ‘budget restrictions’, despite its record low debt ratio. According to Britain’s Guardian newspaper, on the penultimate night of the talks, Switzerland was one of the countries, together with Japan and New Zealand, that opposed the increase from a rather measly 250 billion to a measly 300 billion dollars in climate financing by 2035.

Delegates from the Global South continued their protest even after this decision had been hammered through. Literally, as, with the words ‘It's so decided’, the chairman's little hammer decided when there was ‘consensus’. Chandni Raina, an Indian delegate, described the 300-billion-dollar pledge as ‘staged’ and called the final declaration of the conference ‘nothing more than an optical illusion’. Nikura Maduekwe from Nigeria had another go, saying: ‘This is a joke.’

What Federal Councillor Rösti further said in front of the television camera was also a very bad joke: ‘We can achieve this, for example, if private individuals also contribute.’ Even Larry Summers, a former World Bank Chief Economist, Economic Advisor to the US Government and Deputy Secretary of the Treasury, and to some extent the embodiment of the ‘Washington Consensus’, now refers to ‘private sector capital mobilisation’ as ‘piffle’ from people who ‘wish to appear highly statesmanlike and worthy and/or wish to attract very substantial subsidies’.

Besides, as the top UN official, Simon Stiell naturally had to sugarcoat the COP29 decision on 25 November 2024, but added: ‘So this is no time for victory laps.’

Share post now

global

The Alliance Sud magazine analyses and comments on Switzerland's foreign and development policies. "global" is published four times a year (in german and french) and can be subscribed to free of charge.