Share post now

Press release

Switzerland still one of the darkest corners of the financial world

03.06.2025, Finance and tax policy

In the Financial Secrecy Index published today, Switzerland continues to perform very poorly. Yet, the federal authorities in Bern continue by every means to defend the local financial centre as a contact point for oligarchs, a hotspot for criminal private banks, and a protected space for shady investment advisers. As early as next week, the National Council will again have an opportunity to reverse its position.

© TJN

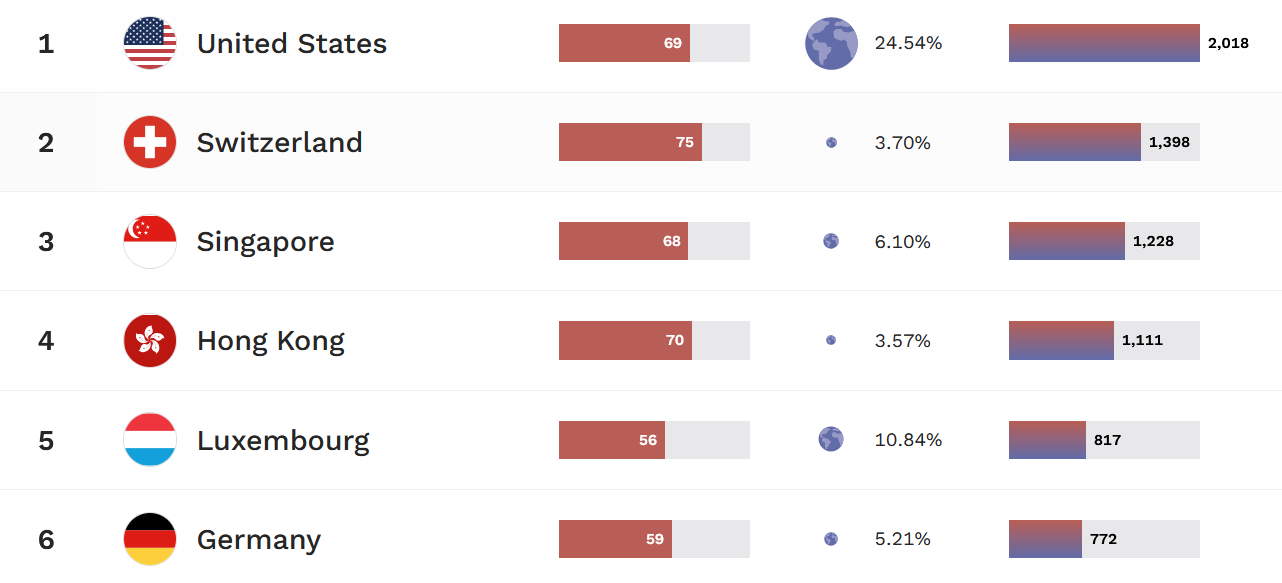

Yet again, the Swiss financial centre performs rather poorly in the latest Financial Secrecy Index (FSI) put out by the Tax Justice Network (TJN). It ranks behind the USA – which, as is well known, is clearly on the verge of transitioning to oligarchy – still in second place on the list of opaque financial centres around the world. Dominik Gross, Expert on Finance and Tax Policy at Alliance Sud, says the following: "Since the previous edition of the FSI three years ago, Swiss policy has come no closer to its long-standing goal of establishing a clean money strategy for the local financial centre." Together with the notorious Guernsey tax haven, Switzerland has the highest secrecy level among the ten worst-rated financial centres.

Opaqueness no longer good for business

That Switzerland is not the frontrunner in opaqueness, as in the past, is attributable not to greater transparency compared with the USA, but to the fact that its financial centre is smaller than that of the USA. The local players’ share of the global offshore pie is diminishing, yet the lack of transparency is growing. Dominik Gross: "This outcome indicates that Swiss politicians are mistaken if they think that opaqueness still drives the asset management business. On the contrary, politicians are harming it with their outdated hide-and-seek approach."

Summer session: an opportunity for greater transparency

The National Council will have an opportunity for a policy reversal as early as next week. As part of its deliberations on the Legal Entity Transparency Act (LETA), it will be voting on the introduction of a corporate beneficial ownership registry, which is now the international standard. However, the Council of States has so drastically undermined it that implementing it will certainly not enhance transparency in the financial centre, but could even damage it. This protects Russian oligarchs, criminal private banks and shady advisers. Dominik Gross therefore has the following demand: "The National Council should return the draft to its Legal Affairs Committee, thereby forcing it to come up with a better alternative, compared with the Council of States".

For further information:

Dominik Gross, Expert on Finance and Tax Policy at Alliance Sud

Phone: +41 (0)78 838 40 79, Mail: dominik.gross@alliancesud.ch

Sustainable finance

For financial flows without environmental degradation abroad

20.03.2025, Climate justice, Finance and tax policy

The Swiss financial centre has demonstrated that it will not voluntarily give up business involving environmental degradation abroad. The Financial Centre Initiative aims to amend the Constitution to include a ban on new investments in coal, oil and gas by Swiss financial market players.

The rainforest in Pará, Brazil, is climatically significant and indigenous land. But it is increasingly being destroyed by deforestation, mines and infrastructure projects - mostly involved are Swiss financial players.

© Lalo de Almeida / Panos Pictures

Felling rainforests helps drive environmental degradation and global warming. That is common knowledge. Besides, illegal slash-and-burn practices often curtail the land rights of indigenous communities and also violate their human rights. Switzerland's banking major UBS knows this. Yet it invests in large Brazilian agribusinesses that are involved in illegal forest clearances in the Amazon, as revealed some time ago by the Society for Threatened Peoples.

Each year, Swiss banks and insurance companies fund or insure billions worth of business operations that degrade the environment and drive global warming. According to a McKinsey study, the Swiss financial centre is responsible for as much as 18 times the amount of carbon emissions generated in Switzerland. Already ten years ago, the international community enshrined in Article 2.1(c) of the Paris Climate Agreement the key role of the financial system in addressing the climate crisis. It laid out the goal of "making finance flows consistent with a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development." Switzerland has ratified the Agreement and is bound by international law to contribute to achieving this goal. Approved by an overwhelming majority of Swiss voters, the Climate Protection Act further requires the federal government to ensure the climate-friendly orientation of financial flows. But implementation is not going smoothly.

"Voluntary" assumes that there is a will

The Federal Council is relying on voluntary and self-regulatory implementation measures by the finance industry, and rejects any additional state regulation. It did, however, support a motion by National Councillor Gerhard Andrey (Greens) which provided for more stringent actions, should the measures in place prove ineffective by 2028. The Parliament rejected the motion in the spring of 2024, however, and saw no need for further action.

We are now seeing that voluntary promises by these banks are not enough.

By January 2025 at the latest, it became clear why the financial sector's voluntary measures and promises were worth so little. The six largest American banks and the world's biggest asset manager BlackRock reneged on the climate promises they had made just four years earlier. Speaking on Western Switzerland television RTS, Professor Florian Egli of the Technical University of Munich said: "We are now seeing that voluntary promises by these banks are not enough. They have reneged on their promises." The UBS, too, is considering withdrawing from the Net Zero Banking Alliance, in which, since 2021, numerous banks had committed to a net zero target by 2050. The banks therefore want to continue funding environmental degradation, if it increases their profits.

The Financial Centre Initiative is needed

Anyone relying on voluntary measures is exposing itself to the whims of the financial sector, which is obviously guided not by climate science but by easy money and political winds. This is no way to combat the climate crisis. The International Energy Agency has long made clear in its Net Zero Roadmap that promoting new fossil fuel extraction is not compatible with meeting the Paris climate goals.

This prompted Climate Alliance Switzerland to launch the "Financial Centre Initiative" in late 2024, jointly with the WWF, Greenpeace and politicians from all the federal parties except the right-wing SVP. It is intended to ensure that no one else operating out of Switzerland finances environmental degradation and global warming. Should the Government and Parliament continue to sit on their hands, the electorate has the power to amend the Constitution to prohibit Switzerland's financial sector from funding or underwriting any additional extraction of coal, oil or gas. The same rules would then govern all players.

Alliance Sud supports the popular initiative in order that Switzerland can finally activate its greatest lever to enhance worldwide climate protection and fully implement the Paris Agreement.

Federal Popular Initiative 'For a sustainable and future-oriented Swiss financial centre (Financial Centre Initiative)’

The initiative aims for:

- the environmentally sustainable orientation of the financial centre, with financial market players aligning their business activities abroad with international climate and environmental goals. Consideration is being given to binding transition plans to be implemented by the companies concerned.

- a prohibition on the funding or underwriting of new fossil fuel extraction projects or the expansion of existing ones.

Alliance Sud supports the initiative because:

- Switzerland is not sufficiently implementing the Paris Climate Agreement through self-regulation by the financial sector.

- the financial centre bears the greatest climate responsibility of all players under Swiss influence. It represents Switzerland's most important lever for helping to achieve worldwide climate protection.

Share post now

global

The Alliance Sud magazine analyses and comments on Switzerland's foreign and development policies. "global" is published four times a year (in german and french) and can be subscribed to free of charge.

International Tax Policy

Signs of hope in the Vatican

20.03.2025, Finance and tax policy

The Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences hosted a meeting on tax justice and solidarity. Yet what hovered above attendees was not the Holy Ghost, but Donald Trump.

St Peter's Basilica, Vatican City. © Keystone/AFP/Tiziana Fabi

You may think what you will of monotheism in general and the Catholic Church in particular, but what is beyond dispute is that social justice is a leading concern for the first Pope from the Global South. Thus, three years ago, Pope Francis was already calling for a tax system that "must favour the redistribution of wealth, and one that protects the dignity of the poor and the lowliest, who are at constant risk of being trampled on by the powerful".

The "high-level dialogue" was jointly hosted by the Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences and the Independent Commission for the Reform of Corporate Taxation (ICRICT, see below) on 13 February 2025. The meeting organisers and venue ensured a "high-ranking" group of participants, including Nobel laureates, professors, former Presidents (current ones like Lula and Pedro Sánchez sent video messages), and representatives of UN organisations and the EU Commission. Of course there were also the NGOs that launched the ICRICT.

The Independent Commission for the Reform of Corporate Taxation (ICRICT) was created ten years ago at the initiative of civil society organisations, including Alliance Sud. On the one hand, it provides expert support, and on the other, it serves as a megaphone. Besides the Co-Chairs Jayati Ghosh and Joseph Stiglitz, the Commission comprises a further 12 members from Africa, Asia, Latin America, Oceania and Europe, including Eva Joly, former European parliamentarian and expert on corruption and money laundering, José Antonio Ocampo, former Colombian Finance Minister, or Thomas Piketty, Professor of Economics, and author of the bestseller "Capital in the Twenty-First Century".

In her opening remarks, the President of the Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences, Sister Helen Alford, said that Pope Francis (who was unfortunately taken seriously ill on that very day) had placed the Holy Jubilee Year 2025 under the motto "Signs of Hope". And signs of hope there were in the shadow of St Peter's Basilica, despite Trump – or precisely on account of him.

Former Prime Minister of Senegal Aminata Touré recalled that each year, Africa loses more money through tax evasion and other illicit financial flows than it receives through development assistance funding and foreign investments in the continent combined. In the light of the important UN meetings taking place this year, such as the Fourth Financing for Development Conference (FfD4) or the Second World Summit for Social Development, she hoped that common sense would prevail, "something we all long for at present".

The fact that under Brazil's presidency, the G20 last year expressed support in principle for higher taxation of the super-rich was seen by many as a sign of hope. French economics professor Gabriel Zucman, one of the fiercest defenders of this idea, explained that of all social groups, people with a fortune of USD 100 million are paying the least taxes. Or, to quote Abigail Disney, grandniece and heir of Walt Disney: "My effective tax rate is lower than that of my janitor." Alas, Zucman did not elaborate further on just what a billionaire tax might look like. Edmund Valpy Fitzgerald, Professor Emeritus of International Development Finance at Oxford, then drew attention chiefly to the problems entailed: the absolutely overwhelming number of billionaires are located in the North, and the cooperation of these countries is therefore needed. Large fortunes in the South must be treated differently from those in the North, and this calls for adapted rules. Then there is the unresolved question of how the tax proceeds could be used to benefit developing countries and who should receive how much. Yet – "the right structure could replace the ODA system through tax-funded transfers based on need and possibilities" – a sign of hope.

After this digression on the topic of individual taxation, the discussion soon returned to the issue that forms part of the name of the Commission: the reform of corporate taxation. There was agreement that the OECD minimum tax is not working and that the UN is the only appropriate forum for global tax matters. Joseph Stiglitz, a Nobel Laureate in Economics, offered the following succinct opinion: "The good thing about bad times is – there is a lot of room for improvement". And he saw the most surprising sign of hope: Trump's withdrawal from the negotiations on a UN Tax Convention. "In the past, the USA always negotiated in the same manner. They drove a hard bargain, forced everyone to make concessions, they watered things down, only to end up neither signing nor ratifying the agreement." So, it's better if they are no longer present at all. He also drew on the pausing of the Corrupt Foreign Practices Act – the anti-corruption law – to put forward a concrete suggestion about a possible way of reacting to Trump. The pausing signals that bribery is again admissible, even "great for American business". Stiglitz said that because this invitation to corruption works just like subsidies, countries could deploy the countervailing measures allowed by the WTO in response to subsidies. Alternatively, they could tax US multinationals for climate financing purposes or in order to cushion the dismantling of USAID. "React creatively to a dysfunctional government in the USA!"

In his video message, Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez was somewhat more realistic. He came out very clearly in favour of taxing the super-rich, called for an ambitious UN Tax Convention, and for observance of the principle whereby taxation takes place where profits are actually generated. "We must address a simple question: do we control global taxation or do we allow the system to control us?" Spain has a key role to play as it will be hosting FfD4 in Seville – its clear language is therefore a sign of hope.

Indian economist and Co-Chair of the ICRICT, Jayati Ghosh, went a step further: "Challenging times are an opportunity to reorganise, build new alliances and find allies in unexpected places. "If, against the backdrop of the berserker in Washington and as the prime mover in the global tax negotiations, European countries were to reach out to Africa, that would be more than just a sign of hope.

Share post now

global

The Alliance Sud magazine analyses and comments on Switzerland's foreign and development policies. "global" is published four times a year (in german and french) and can be subscribed to free of charge.

International Tax Policy

"The system is set up against us"

29.11.2024, Finance and tax policy

Everlyn Muendo is following the UN negotiations for a framework convention for international cooperation in tax matters on behalf of the Tax Justice Network Africa (TJNA). In this interview, she analyses the current developments in the process in New York and explains why there is no longer any alternative to the UN for the Global South when it comes to international tax policy. Interview: Dominik Gross

Tax revenue is flowing to the north, the cost of living is rising: Violent protests against unjust fiscal policy reforms have been shaking Kenya since June. © Keystone / AFP / Kabir Dhanji

Alliance Sud: Everlyn Muendo, you participated in the negotiation sessions for a UN framework on international tax cooperation in New York this year. What is your general impression of this process so far?

We experienced a very clear and sharp political divide in terms of the positions between the Global North and the Global South. Overall, through all the sessions, we could clearly see what the positions of the Global North and of the Global South were.

The transparency of the negotiations is already a big step forward compared to those in previous years at the OECD in Paris. Where do you see the major issues resulting in this divide between North and South?

I would summarize the positions of the Global North into the following issues. Firstly, they think that the UN framework convention should play a complementary role to the OECD and shouldn’t – as they call it – duplicate its work in the field of international tax cooperation. So obviously the work of the OECD in this field. Secondly, their goal seems to be to diminish the role of the UN only to capacity building, which means to offer support in terms of infrastructure and expert education for tax administrations in the Global South. This is the result of a profound misperception of the situation of the Global South: They seem to think that we don’t have adequate capacities. In their view this is the reason for the international tax system not being inclusive or effective. This is a disingenuous argument, because even during the inclusive framework process of the OECD some developing countries articulated substantive and significant concerns about the overall direction of the global minimum tax and the redistribution of taxing rights to market countries. But those concerns were constantly ignored.

In the UN framework convention process, the countries of the Global South are strongly pushing to address the systemic issues.

How were these concerns ignored?

For instance, developing countries were obviously not comfortable with setting the minimum tax rate to fifteen percent. We wanted a much higher rate. But we still ended up there. Some countries went as far as rejecting the so called Two Pillar Solution of the OECD back in 2021. These were Nigeria, Kenya, Sri Lanka and Pakistan. But still, nothing was substantially done to change the way these proposals were framed. That’s why I think it is very disingenuous to say it is a capacity issue. It is the substantive rule making that needs to be changed. As I said in my statement during the negotiations in April in New York, you can’t capacity build us out of imbalanced taxing rights. In the UN framework convention process, the countries of the Global South are strongly pushing to address those systemic issues.

So, countries of the Global North are trying to avoid the crucial issues in this process?

Yes, I think so. My impression is that they are not negotiating honestly. But in international negotiations it is a fundamental principle that both parties are supposed to negotiate in good faith. They are also obligated to implement the treaties and the obligations that they have agreed on in good faith. For instance, to say that we need more technical analyses, does not build confidence. We have the UN secretary general’s tax report on the status of international tax cooperation, which was particularly looking at how the lack of inclusiveness in international tax cooperation is making international tax cooperation ineffective. So, we have proof of our arguments, it’s all there.

How is the coordination between African countries working?

I think the Africa Group is doing its best with the limited resources that are available, both on the human and the technical level. I think we also have seen a lot of great leadership from the African Union commission and the Pan African bodies – the UNECA (UN Economic Commission for Africa) and the ATAF (African Tax Administration Forum) – in organizing and informing African countries of what is at stake at the UN.

Everlyn Muendo

Kenyan Everlyn Muendo is a lawyer at the Tax Justice Network Africa (TJNA). She works on the question of how international tax policy influences development financing in African countries.

How can we as a global civil society coalition best challenge the position of the EU or Switzerland speaking off “duplication” and “capacity building”?

First, it just needs to be acknowledged, that the OECD initiatives and processes such as the development of the automatic exchange of information or the one of the minimum tax for multinationals are not working for a significant group of people, particularly in countries of the Global South. That’s why they are seeking to create another forum for international tax cooperation which should be inclusive. This is clearly defined in the UN resolutions on which the process has been based since 2022. Secondly, there is no other universal initiative on global tax cooperation. Some may say we could regard most of the work which has been done at the OECD as regional level work. The question is then what would be the criteria for picking and leaving certain aspects of what has been done. For example, Pillar 1 of the OECD BEPS II project which is supposed to be about reallocation of taxing rights will probably never be completed. These aren’t issues which we can give more time to.

Countries agreed on the Terms of Reference of the convention with a 2/3 majority. What is at stake now?

Tax is such a critical issue when it comes to financing for development. It is not just about technical issues like profit allocation rules or the division of taxing rights. It is about building up decent education systems for all or about fighting the public health crisis in the Global South. The reason for the dramatic problems in both fields is a constant underfunding of public services in those countries. At the end it’s about human beings. Our inaction brings about victims and that’s why we really want to move forward with this process. It is also about generating resources to finance climate protection. Although we – compared to the Global North – contributed very little to the climate crisis, we are severely affected by it.

On the African continent you can’t speak about international taxation without speaking about taxation of natural resources, particularly those of the extractive sector.

What would be the key solutions for resource-rich countries in Africa?

On the African continent you can’t speak about international taxation without speaking about taxation of natural resources, particularly those of the extractive sector. Most multinational enterprises within the continent are part of the extractive industry. But their headquarters are obviously in developed countries. It’s actually a very complicated issue and goes way back into our colonial history. Before colonialists left, they made sure that even after independence our economies would be structured in a way that benefits them the most. So, instead of building up food security for instance, our economies have been structured in such a way that we would essentially continue to produce coffee, tea, crops and commodities that are of most value to developed countries. Essentially, we export all these raw materials, and the added value is made outside the continent. On the other side all the final products resulting from industrial production in the Global North based on our raw materials are then sold back to us. We don’t gain as much as we should from our own resources in comparison to countries who don’t have these commodities at all.

Can you give us an example?

Which country is known for good chocolate? It’s not Ghana.

Switzerland?

Exactly! This is a striking fact if you consider that over half of the cocoa beans imported into Switzerland comes from Ghana. Because of harmful tax practices and aggressive tax planning by multinationals hundreds of billions of dollars in profits are shifted away from African countries. Even with the economic activities which foreign companies are carrying out and the income they’re generating through our resources we don’t get our fair share of taxes. Instead, the tax revenues go primarily to the residence countries of the multinationals. The system is really set up against us.

It will take some time until new UN rules based on a future framework convention will bear fruit. Are there current opportunities for improvement outside this process?

We are also fighting for more bilateral double tax treaties based on the UN model rules which are much better than their counterparts at the OECD, but we haven’t been so successful with that. By nature, a single country from the Global North has a lot of power when it comes to negotiating a bilateral agreement. And some of those countries are bullies! The imbalance of economic power really plays out here. So even if African or developing countries in general do have a lot of capacity, they still end up giving away a lot of our taxing rights. That is happening because we feel the pressure that we still must attract foreign direct investment from a partner country to fuel economic development. I like to call that the FDI fallacy in Africa.

Everlyn Muendo at a discussion of the Tax Justice Network Africa on tax and climate justice this November in Nairobi. © TJNA

The Kenyan society faces huge tensions because of a recent new finance bill issued by the national government. Can you explain what is happening there?

The June 2025 Finance Bill protests were bigger than the Finance Bill itself. They were an expression of the frustration of hardworking Kenyans with the increasing economic injustices. The Kenyan government is highly indebted and desperately needs to raise resources for debt servicing and development. But it is introducing taxes that have a heavy bearing on the cost of living. These include a proposed eco-levy, a motor vehicle tax, increased road maintenance levies and removing VAT exemptions on certain crucial items, amongst others. These taxes are highly regressive yet at the same time, we receive very little value for our money in terms of public services. The bulk of the revenue is spent on debt servicing, which can take up more than 50% of the revenue, and on corruption which crowds out critical public services.

What are the consequences?

There is a breakdown of public services such as health and education. For instance, there have been severe pay cuts for public servants such as medical interns whose salaries were reduced. Additionally, a new university funding model was introduced. This model skyrocketed university fees leading to a huge public outcry. Kenya has become a hub for experimentation on fiscal consolidation measures. Ordinary Kenyans are losing twice!

How can you – as Switzerland - talk about corruption in the African continent, while you are the biggest enabler of secrecy perpetrating illicit financial flows?

What do you say to the accusation, that more public revenue in African countries would disappear due to corruption anyway?

How can you – as Switzerland - talk about corruption in the African continent, while you are the biggest enabler of secrecy perpetrating illicit financial flows? Seriously, all I can say, it needs two to tango. On the one hand there is an African official who is corrupt, but who is giving him the bribe? A lot of corporations! We had Glencore from Switzerland. The corruption cases this corporation has been involved in are very telling. We also must recognize the role secrecy jurisdictions like Switzerland have played in this by being a haven for these corrupt individuals and officials in our countries. That’s why a lot of this wealth is held offshore. Nobody says, oh I am going to hide my money in Kenya. No! It’s Switzerland! You are infamous for a reason!

How is all this related to tax avoidance of multinationals?

Aggressive tax planning and corruption are the same. They are both immoral, they both have the same overall effect of bleeding out resources. But one is legal, one is not. And this is why you find a lot of African countries that prefer using the term illicit financial flows (IFFs), where we are grouping all these activities together and trying to produce a continental level strategy to address it – whether they are legitimated by law or not. Particularly the commission of the African Union is doing a lot in this regard with the support of the UN.

Let us get back to the UN. The next negotiations are due in February 2025. Could the positions of the Global North change?

Well, there are two interesting developments in this regard: Firstly, the EU states abstained in the vote on the key elements of the convention in August instead of voting no, as they did on the previous resolutions. This is a sign that the Global North's extraordinarily strong skepticism towards the process itself is easing. That could have a positive impact on the next rounds of negotiations. Secondly, Donald Trump's victory in the US presidential elections could lead to the USA completely blocking both OECD and UN processes. Up to now, the countries of the North have always said that decisions at the UN need to be made by consensus. However, I think that they will now have to adjust this position in view of the developments in the USA.

Going to the UN is our way of addressing fundamental challenges.

What would you like to change?

Wouldn't it be better to be satisfied with simple majority decisions, even if consensus is the ideal? Sometimes things just do not go according to your own ideal. Instead of being held back by a single country or a small group of countries, it would be more democratic to allow everyone else – whether from the Global North or the Global South – to move forward. However, if decisions are made by consensus, the USA, as the economically strongest country, has a virtual veto power. It would be much more democratic to give every country an equal vote in majority decisions.

Where do you see positive developments on the African continent?

In several African countries we see a political process today, in which people push for stronger accountability systems of our own leaders, politically and economically. Especially in West Africa, for example in Senegal. The uprisings we have recently experienced there showed to a certain extent also an extreme expression of the desire for self-determination in societies which we can still call postcolonial. No matter if you look from trade to debt to tax to whatever: we may have political sovereignty, we may be recognized states by international law, but we are far from economic sovereignty. Going to the UN is our way of addressing those fundamental challenges because tax sovereignty is a very crucial part of economic sovereignty overall.

Share post now

global

The Alliance Sud magazine analyses and comments on Switzerland's foreign and development policies. "global" is published four times a year (in german and french) and can be subscribed to free of charge.

Climate and Taxes

A duo on a world tour

04.10.2024, Climate justice, Finance and tax policy

Without the polluter-pays principle, international climate policy cannot be funded – without tax justice, it is not feasible. A mini-world tour with an unequal but perhaps soon symbiotic duo.

More and more activists and multilateral forums around the world are linking demands for tax and climate justice. Protesters at the Fridays for Future parade in Berlin, 20 September 2024. © Keystone / EPA / Clemens Bilan

It is really immediately clear – to be able to afford transitioning away from fossil fuels without major social dislocations, we must raise the requisite funds from those industries that were the first to enrich themselves from them, namely, the fossil fuels industry. Studies show that more than half of all worldwide emissions since 1988 can be attributed to the exploitation of fossil fuels by just 25 companies. No one has ever paid up for the long-term costs being engendered by these emissions, which are causing climate change. At the same time, the profits and dividends accruing to those trading in these fuels have risen continuously. Thanks to the price increases triggered by Russia's invasion of Ukraine, the 2022 profits of oil and gas companies skyrocketed to four trillion dollars

Make polluters pay

It is therefore no surprise that in the context of the urgent need for climate funding for the Global South, and in keeping with the polluter pays principle, the call is growing louder for additional taxation of these companies. This goal has long been present in international civil society under the slogan "Make polluters pay". A current study by the Heinrich Böll Foundation shows that in this very decade, a CO2 tax on the production of coal, oil and gas, called a Climate Damages Tax, would yield 900 billion dollars in OECD countries for managing the climate crisis.

The call for international CO2 taxes is almost as old as the Framework Convention on Climate Change itself. As early as 2006, the then Swiss Federal President Moritz Leuenberger used the Climate Conference to call for a global CO2 tax. Concrete agreement at the UN never stood a chance, however. But in view of the UN negotiations on a new climate finance target at the COP29 this coming November in Baku, pressure is growing for the available funding to be increased. This has recently prompted a range of players and countries to call for international CO2 taxes or other methods of financing based on the polluter-pays principle. The approaches vary widely, spanning national tax on profits from oil extraction, voluntary contributions from the extraction industry, and legally requiring enterprises to accept climate accountability. All approaches to international taxes will, however, require political will at the national level. Switzerland, too, should levy "polluter-pays" taxes on enterprises that profit from the fossil fuels business, in that way increasing its contributions to international climate finance.

The "gilets jaunes" – or how not to do things

Additional funds could be raised for ecologically restructuring our societies not only by levying additional taxes on fossil fuel producers, but also if governments asked their consumers to pay more. However, if the restructuring is to be not just ecological but also social, caution is advised when deciding on the right type of CO2 consumer tax. France, for example, has unpleasant memories of the violent street clashes between the "gilets jaunes" (yellow vests) and the police about six years ago in the middle of Paris. Those protests were triggered simultaneously by an increase in the fuel tax (eco-tax) that the French President wanted to levy on every litre of diesel being dispensed by that country's petrol pumps. By his reckoning, it would have garnered an additional 15 billion euros in revenue for the State. But this tax would have affected everyone equally: rich and poor, including people racing their Porsche TDI along empty French country roads, as well as those living in far-flung, non-metropolitan parts of France badly served by public transport and dependent on their rickety diesel vehicles in everyday life. The "gilets jaunes" movement was therefore supported not only by climate deniers and automobile enthusiasts, but also by many people whose already tight monthly budgets would have been busted by this diesel tax. This toxic mix constituted political dynamite. The liberal French government backed down and also slowed the pace of its climate policy agenda. At the same time, President Macron further renounced the reintroduction of a "solidarity tax" on high net-worth individuals, which had been introduced in the 1980s by the long-standing socialist President François Mitterrand, and which Macron had abolished as one of his first official acts in power. That would possibly have taken the social policy wind out of the sails of the "gilets jaunes".

No climate justice without tax justice

Today there is a highly progressive wealth tax with a social and environmental dimension, among other places, on the agenda of the G20 countries. In a report published in November 2023, the NGO Oxfam International concludes that a global wealth tax on all millionaires and billionaires would raise 1700 billion dollars annually worldwide. An additional penalty tax on investments in climate-damaging activities could bring in a further 100 billion dollars. Combining these measures with a 60-per cent income tax on the 1 per cent with the highest incomes would generate an additional 6400 billion. Depending on business cycle and price trends, an excess profits tax can also generate massive amounts of additional revenue. According to Oxfam, such a tax would have raised another 941 billion dollars in each of the years 2022 and 2023 when inflation was high. These measures therefore have the potential to garner an additional tax take of at least 9,000 billion in a single year.

The premise of the 2024 report on the funding of sustainable development published by the United Nations Department for Economic and Social Affairs (DESA) is that the funding and investment shortfalls in connection with the UN Sustainable Development Goals of the 2030 Agenda amount to 2500 to 4000 billion US dollars. Using just the tools mentioned above, the 2030 Agenda could therefore be easily funded up to 2030 – to say nothing of reforms in other areas of development finance. Unlike Macron's diesel tax, a global wealth tax would certainly be in line with the polluter-pays principle within the meaning of international climate policy. According to Oxfam, in 2019, the world's richest 1 per cent accounted for 16 per cent of all global CO2 emissions. This meant that they produced as much CO2 as the poorer 66 per cent of the world's population, that is to say 5 billion people.

Climate and tax justice on a world tour: an overview of some global approaches and initiatives

- Washington D.C. – Climate Damages Tax: Current study by the Heinrich Böll Foundation on a CO2 tax on coal, oil and gas production. While some of the proceeds would be earmarked for the UN fund to cover climate-related loss and damage, another portion would go towards managing the climate crisis domestically. Producing countries in the Global South could also introduce the tax and use the proceeds in their own countries. Increasing the tax annually would also create an incentive to phase out fossil fuels. Civil society endorses this concept.

- Nairobi – Africa Climate Summit: Already a year ago, African countries called for global CO2 taxes on the trade in fossil fuels, on marine and air traffic, and also for a global financial transaction tax, in order to boost investment in climate protection.

- Baku – Climate Finance Action Fund: As President of COP29, Azerbaijan is keen to build up a climate fund that is fed by voluntary contributions from coal, oil and gas producers. The fund's Board of Directors would decide on the distribution of the monies raised from the participating production industry. The previous COP host, the United Arab Emirates, proved that this is not a good idea. Climate Home News recently uncovered the fact that resources from their newly founded climate fund were being invested in natural gas projects and airports.

- Paris – Task Force for Global Solidarity Taxes: Last year, France, Barbados and Kenya formed a task force to work together with other interested countries on ideas for global solidarity taxes applicable to the fossil fuels industry, financial transactions, as well as marine and air traffic. Civil society observers in France, however, view this as both international image cultivation by President Macron and a diversion from international negotiations on climate finance or the UN Tax Convention.

- London – Excess profits tax on oil and gas production: Following the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, the United Kingdom introduced an excess profits tax on companies producing oil and gas in the UK, and raised 2.6 billion pounds in the first year. The new Labour Government is planning to further increase the tax rate. The proceeds go into government coffers.

- Pari Island (Indonesia) – Lawsuit against Holcim: Pari Island is being flooded with growing frequency and is being swallowed up by the sea, metre by metre. Four residents have initiated litigation in the Zug Cantonal Court against the Holcim cement company over its climate responsibility, and are demanding that the company reduces its emissions, pay compensation for the climate damage they have suffered, and contribute financially towards adaptation to global warming.

- Rio de Janeiro – Global wealth tax: In late June, G20 finance ministers discussed a model for the global wealth tax devised by the French economist Gabriel Zucman. In principle, it reflects what Oxfam proposes in its report (see text). As President of the G20 this year, Brazil raised the idea in the club of the world's 20 leading economies. After much fanfare in the early stages, the summit's final declaration could only produce fine-sounding rhetoric. The project had reportedly been hampered, among other things, by disagreement among participants over the question of whether the UN or the OECD should be tasked with working out such a tax.

- New York – UN Tax Convention: Negotiations between the 197 UN member governments on the Terms of Reference (ToRs) of a Framework Tax Convention concluded successfully in mid-August. From the very beginning, many countries – especially those in the Global South – had come out in favour of including in the ToRs the creation of more effective climate and environmental taxes as an aim of the Convention in its own right. Despite having been highly controversial, this point is now embodied in the text and promises long-term global progress on climate-related taxes with redistributive effects. Elaborating a global wealth tax with a climate-related dimension would be best placed in the hands of the UN, where the prevailing majority dynamics will ensure that such a taxation model would also reflect the specific interests of the countries in the Global South.

- Berne – Initiative for a Future: The Young Socialists wish to impose a 50-per cent tax on inheritances of more than 50 million francs. The Confederation and cantons would then use the proceeds of the tax to "combat the climate crisis in a socially equitable manner and to fund the complete overhaul of the economy that this would require." This is stated in the text of the initiative. As it is well known that the climate crisis cannot be tackled strictly within the borders of Switzerland, the initiative also provides for additional contributions by Switzerland towards the funding of the UN Sustainable Development Goals worldwide.

COP29 – Climate Conference

In November, UN Member States will negotiate a new collective funding target for supporting the countries in the Global South in dealing with the climate crisis. Funding in accordance with the polluter-pays principle is also a part of this discussion. The funding gap is growing dramatically and financial support is simply a necessity if the countries in the Global South are to continue their development using climate-friendly technologies, and avoid more loss and damage thanks to adaptation measures. The pressure for an ambitious funding target is accordingly great, and rich countries are challenged to increase their contributions significantly in the years ahead.

Share post now

global

The Alliance Sud magazine analyses and comments on Switzerland's foreign and development policies. "global" is published four times a year (in german and french) and can be subscribed to free of charge.

UN tax convention

Temperatures also rising on the tax policy front in New York

26.07.2024, Finance and tax policy

Next week ushers in another round of negotiations on a Framework Tax Convention at the UN headquarters in New York. Recently, the Swiss Cantons of Basel City and Zug, noted for their low corporate tax rates, again provided new material illustrating why this is an absolute necessity.

Until mid-August, countries from the Global South in particular will be campaigning in New York for a strong UN tax convention - this is likely to make Switzerland and other profiteers of the current tax system sweat. © KEYSTONE / SPUTNIK / Sergey Guneev

Over the next three weeks, the Ad Hoc Committee to Draft Terms of Reference for a United Nations Framework Convention on International Tax Cooperation will be determining the policy scope of the new Framework Convention and also its decision-making procedure. What sounds extremely technical is of great political significance in that, by mid-August, negotiators must determine how much power the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) will hand over to the UN, having dominated the multilateral agenda in international tax policy matters since the 1970s. Should the UN take over the reins in global tax policy in the future, the countries of the North – which continue to dominate economic policy despite the rise of China – would be relinquishing some of their supremacy in this key aspect of tax policy. As might be expected, there is great resistance to a robust UN tax convention from the EU, the USA and the erstwhile beneficiaries of the OECD-led international tax system, i.e., low corporate tax jurisdictions and major financial centres. Both business models benefit from the fact that, despite all the OECD reforms of the past 10 years, corporate profits and assets can still be taxed where rates are lowest or not be taxed at all.

The South in a key position

Negotiating multilateral tax questions in the UN instead of the OECD will alter the majority structure, placing the countries of the South in a key position. The Draft Terms of Reference (ToR) recently released by the Bureau of the Ad Hoc Committee reflects this. The text directly links the tax convention with the funding of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and states the Convention’s aim, among other things, to "Establish an inclusive, fair, transparent, efficient, equitable, and effective international tax system for sustainable development". This aim is to be achieved in the following areas through the corresponding undertakings by signatory countries:

- The fair allocation of taxing rights vis-a-vis multinational enterprises,

- the effective taxation of high-net worth individuals,

- ensuring that tax measures contribute to addressing environmental challenges,

- effective transparency and information sharing for tax purposes,

- the effective prevention and resolution of tax disputes.

Should all these elements be included in the final version of the ToR, all major contemporary problems of international tax policy could in future be addressed in the UN framework: profit-shifting by multinational enterprises to low-tax jurisdictions; high-net worth individuals, who use cunning constructs to evade tax authorities in the global offshore system; the fact that today, taxes are not nearly being sufficiently harnessed as a tool for economic management in the climate policy framework; the lack of transparency in global asset management, and the absence of a level playing field between countries of domicile of multinational enterprises, those that are their markets, and those where their production takes place, when it comes to settling disputes over questions of who may tax which profits of these enterprises, and where. The strong opposition from the Global North is therefore no surprise, even though it is rarely ever made truly explicit.

Unconstructive Switzerland

Switzerland's position on the Draft Terms of Reference is symptomatic of this negotiating tactic adopted by the rich countries, which opt for subterfuge rather than explicitly laying out and defending their own interests. Like most OECD and EU countries, Switzerland favours decision-making by consensus, as the only way to implement, in practice, the multilateral reforms to the international tax system taken up in the Convention. At the same time, Switzerland wishes – again in line with the OECD majority and the EU – to negotiate in the UN framework only topics that have not yet been addressed in the OECD. This excludes corporate taxation, tax transparency, better taxation of high net worth individuals, and new dispute settlement mechanisms. In this connection, Switzerland speaks of a duplication of multinational forums.

However, the ongoing worldwide implementation of the OECD minimum tax clearly shows that talk of "duplication" can only come from a privileged Northern perspective. For the Global South, the minimum tax yields practically nothing, and it will benefit the very same low-tax jurisdictions that have exploited the shortcomings of the corporate taxation system in place hitherto, in order to tax profits amongst themselves while the underlying wealth creation itself takes place elsewhere. Only those who are thriving under the OECD system can regard a new intergovernmental forum at the United Nations as "duplication", in other words, as basically superfluous.

Pondering blockchain instead of sustainable development

This undoubtedly applies to Switzerland. The Swiss Cantons of Basel City and Zug are good examples. While it is Roche, Novartis and company that ensure the generation of eye-watering levels of profit tax revenue and massive budget surpluses (+434 million in 2023) in Basel, it is mainly the commodity traders that play this role in Zug (460 million). A disproportionately large profit tax base is generated in both cantons, considering that the branches domiciled there actually create wealth mainly abroad (production of medicaments and also much of Research & Development do not take place in Basel, while Zug has no copper mines or oilfields). Both expect more revenues to flow into the cantonal coffers with the introduction of the OECD minimum tax. But even at this stage, both cantonal governments no longer seem to know what to do with all that money. They are both planning to use new subsidy instruments to return the additional tax revenues to the very companies that have to pay the minimum tax. In Basel, this is being presented, among other things, as promoting equality (the canton is planning, for example, to partially fund parental leave for employees of highly profitable corporations). Zug has evinced a sudden onset of social policy progressiveness. In the next two years, the canton is expected to assume all hospital costs incurred by its residents. It will also provide support in childcare, free access to top-class medical care – both being crucial components of sustainable development. Workers in the pharmaceutical factories of South Asia or the mines of Africa operated by corporations domiciled in Basel and Zug can only dream of these two things. Yet, no-one in the governments of the two luxury cantons has thought of investing the surplus tax revenue in sustainable development in the Global South. Instead, the Canton of Zug (still striving for Crypto Valley status) prefers to buy an entire university institute for blockchain research in neighbouring Lucerne.

No trace of any worldwide duplication of Zug's prosperity. Instead, the OECD regime obviously obeys the principle whereby, "to him that hath, more shall be given". This alone is reason enough to strive for a fair global tax system under the UN umbrella. It is a given that this will not please Swiss officialdom, so long as it fails to fundamentally overhaul its own business model.

For further information and an overview of the tax negotiations within the UN, read also the Briefing Paper (in German), written by the Global Policy Forum and the Netzwerk Steuergerechtigkeit (Tax Justice Network), among others.

Share post now

Article, Global

Banks' climate initiatives: a major disappointment

27.06.2024, Finance and tax policy

To align themselves with the Paris Agreement, banks have established and extolled the virtues of voluntary climate alliances. A recent European Central Bank study shows them to be ineffective.

Huge quantities of coal are powering giant aluminium plants in East Kalimantan, Indonesia.

Swiss banks are involved in these supposedly "green" plants. © Dita Alangkara / Keystone / AP Photo

In November 2021, US Treasury Secretary Janet L. Yellen told the COP26 in Glasgow that “the private sector is ready to supply the financing to set us on a course to avoid the worst effects of climate change”. Under pressure to support the economic transition away from carbon-intensive activities – or, in other words, to “align themselves with the climate goals” of the Paris Agreement – financial players worldwide have joined in a series of voluntary climate-related initiatives. They include the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ), spearheaded by former Bank of England Governor Mark Carney, and billionaire financier Mike Bloomberg.

At the launch of the GFANZ at the COP26, some 100 banks, insurers and asset managers committed to injecting capital worth USD 130 trillion to bring down CO2 emissions and fund the energy transition. Under that commitment, the projects and businesses funded by the loans from signatory financial institutions would have to be “net zero” by 2050, i.e., they should balance the amount of greenhouse gases emitted with the amount removed from the atmosphere. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), achieving climate neutrality by 2050 will require annual investments of USD 2’000-2’800 billion in clean energy in developing and emerging countries alone. The announcements made in Glasgow by the financial sector elicited high hopes in some quarters... and a healthy dose of scepticism in others.

In a recent study by the European Central Bank (ECB), however, researchers examined the impact of EU banks' voluntary climate commitments – chiefly the Net Zero Banking Alliance, being one of the eight sectoral initiatives making up the GFANZ – on their lending behaviour and in terms of the climate impact of these practices on corporate borrowers. The findings are an embarrassment for the financial players involved.

Profile of signatory banks

The NZBA signatory banks (hereinafter “NZBA banks”) head-quartered in the Eurozone are mega-banks that devote more of their funding to “brown” sectors, with a greater portion of their loans going to the mining sector (including coal, oil and gas), and a smaller portion to sectors classified as “green” under EU taxonomy. NZBA banks' own priority objectives are power generation, oil and gas, and transport.1 As regards motivation, the study shows that banks are making voluntary climate commitments to boost their ESG (Environmental, Social, Governance) rating and reap reputational and financial benefits, especially when it comes to institutional investors.

The implications for divestment

Sectoral targets represent a voluntary commitment by banks to reducing the emissions they fund by 2030 and 2050, compared to a predetermined baseline. Should the banks choose to meet their targets by divesting, this should mean less funding for the targeted sectors.

The study finds that NZBA banks have cut back their lending to priority sectors by some 20 per cent. At first glance, this would seem to confirm the hypothesis that banks are disengaging from “brown” sectors. But this is not the case. The study found no evidence of reduced investment by NZBA banks – any more than their non-signatory competitors – in priority sectors, or in other high-emission enterprises such as mining companies or companies whose activities are not classified as “green” under EU taxonomy. NZBA banks also did not increase their lending to “green” companies as defined by EU taxonomy after joining the alliance. The study concludes that this casts doubt on the assumption that NZBA banks are actively divesting from “brown” sectors and investing instead in “green” sectors.

No penalties for polluting companies...

The study further shows that the banks' climate commitments have not led to increases in interest rates for the funding of "brown" companies. The observed increase does not exceed 0.25% for priority sectors and 0.55% for the mining sector. Nor do NZBA banks apply lower rates to "green" businesses as defined in EU taxonomy. In other words, the banks neither penalise bad performers nor reward good performers!

... or leverage effect on companies

The ECB study shows that the NZBA has no leverage effect on companies. Indeed, rather than divesting, "climate-aligned" banks can pursue a strategy of "engagement", by pushing corporate borrowers to cut their emissions. They could first insist that the companies to which they lend should set their own climate targets. Indeed, if a company commits to reducing its carbon emissions, the first step is to set a decarbonisation target, which specifies the amount by which the company aims to cut its emissions and the timeline for that reduction. This is tantamount to laying out a climate transition plan.

However, despite the increase in the number of companies that have set such targets since 2018, those borrowing from NZBA banks showed no greater propensity than others to set climate targets. In other words, NZBA banks have no specific climate leverage over companies by way of their engagement.

No impact from voluntary initiatives

Since the signing of the Paris Agreement, financial institutions have announced – with great fanfare – their intention to factor climate considerations into their lending and investment decisions. The findings of the ECB’s first-of-its-kind study brought the lack of impact of the Net Zero Banking Alliance into sharp focus. Although NZBA banks have reduced the volume of their lending in emission-intensive sectors, the "divestment" is no greater than that of non-signatory banks. Moreover, the study is very clear about the outcomes obtained through engagement strategies: corporate clients of NZBA banks are no more active in setting decarbonisation targets than others. The ECB researchers themselves conclude that their study’s findings hold crucial implications for the ongoing debate about "greenwashing" and whether credit rationing by banks can help the global economy realise its net-zero emissions ambitions. As such, there is still every reason for frustration and bewilderment.

From the voluntary to the mandatory

This discussion is now at a turning point. The year 2024 will be decisive in the EU as regards the climate transition plans which financial institutions, too, are expected to formulate. Indeed, such transition plans are central to a new European regulatory architecture, the precise contours of which are yet to be laid out or harmonised.2 If they are to be effective, these transition plans must avoid a narrow approach to short- and medium-term climate risk management, and instead encourage banks to reorient their activities in favour of transition. The oversight bodies must be invested with powers, and penalties imposed in the event of non-compliance. An initial step will be taken in Switzerland with the publication – from 2025 onwards – of the first "mandatory climate disclosures“, including by banks, and which are also expected to contain “a transition plan that is comparable with the Swiss climate goals”. Regrettably, the regulatory framework is still imprecise and leaves room for interpretation as to what exactly is required in terms of climate transition plans. These initial reports will therefore have to be carefully scrutinised to gauge the relevance (or otherwise) of this new approach.

The Net Zero Banking Alliance

So far, the most important voluntary climate initiative launched by banks is the Net Zero Banking Alliance (NZBA). It is supported by the UN and comprises 144 members from 44 countries representing some 40 per cent of total assets under management. Several Swiss banks are on board, including UBS (co-founder), Raiffeisen and the cantonal banks of Zurich, Berne and Basel. In signing the commitment, banks undertake to “align lending and investment portfolios with net-zero emissions by 2050”, with “intermediate targets for 2030 or earlier”. These targets must refer to the sectors being prioritised by the banks for decarbonisation, i.e., the most greenhouse gas intensive sectors in their portfolios, and on which the banks can have a significant impact. Furthermore, banks must publish a transition plan explaining how they intend to achieve their sectoral targets. While still at a preliminary stage, the combination of detailed target setting, UN monitoring and outside validation makes the NZBA a stringent, if not the most stringent climate initiative for banks.

1 Three years after signing, the banks must have set targets for the nine sectors designated by the NZBA, namely, agriculture; aluminium; cement; coal; commercial and residential real estate; iron and steel; oil and gas; power generation; and transport.

2 The main aim is to ensure coherence between the approaches of the Capital Requirements Directive (CRD), the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), and the very recent Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD).

Share post now

global

The Alliance Sud magazine analyses and comments on Switzerland's foreign and development policies. "global" is published four times a year (in german and french) and can be subscribed to free of charge.

UN tax convention

The South on the offensive

13.06.2024, Finance and tax policy

Negotiations are now in progress at the UN on the future drafting of the Framework Convention on International Cooperation in Tax Matters. Our tax policy expert was on hand, and was impressed by the negotiating strength of the African countries.

Delegates at the UN Tax Convention meeting in New York in May 2024. The spearhead for more tax justice

through a shift from the OECD to the UN includes Nigeria. © UN Photo / Manuel Elías

The UN is not its own best PR agency, and certainly not when it comes to tax policy. Hence the failure of world public opinion to notice that at the end of April, something historic was occurring inside the UN headquarters on the East River in New York. For the first time in history, the governments of the 196 UN Member States assembled there to negotiate the future shape of the UN Framework Convention on Taxation, the drafting of which was decided by the General Assembly this past December. The main driver of the process is the group of African countries at the UN, known as the "Africa Group". The countries of the Global South (G77) have never made as much headway with their tax policy concerns at the UN as they have in the past six months.

The organisational and substantive structure of the tax convention is now to be hammered out by August of this year, i.e., the "Terms of reference" are to be negotiated. If the General Assembly approves them in September, the convention itself and the details of its content can then be drawn up. That would constitute the basis on which legally binding tax reforms could then be formulated, and which would have to be implemented by Member States thereafter. This therefore represents a one-off opportunity for the countries of the Global South and the global tax justice movement to end the OECD's dominance in international tax policy and make the UN the central player, thereby laying the organisational groundwork for a more just multilateral tax policy.

The dilemma of the North

The past 60 years have witnessed several such attempts to end the fiscal dominance of the rich countries of the North. Today, the outlook is brighter than ever, for two main reasons:

- The OECD has proved a disappointment as regards its reforms to multinational corporate taxation. When the BEPS 2.0 (Base Erosion and Profit Shifting) negotiation process began in January 2019 – it ultimately produced the minimum tax in autumn 2022 – the aims were still to prevent tax avoidance by multinational corporations in cross-border trade, distribute profit tax revenues more fairly worldwide, and halt the international race to the bottom in corporate taxation. After five years of negotiations, the OECD has been unable to produce anything more than this version of the minimum tax, of which the additional proceeds are flowing, of all places, into existing low-tax jurisdictions for corporations in the North, rather than to places where the corresponding profits are being generated. There is great frustration in the Global South over this outcome. The aim is now to resolve the injustices of the present international tax system also beyond the confines of corporate taxation, and within the United Nations framework.

- Global political developments of recent years and the concomitant new experiences of marginalisation at the multilateral level have united African countries on tax policy matters. Those experiences include discrimination regarding access to vaccines during the Coronavirus pandemic, the refusal of creditor states in the North to effectively tackle the sovereign debt crisis in the Global South, or the international community's failure to act to counter the food crisis in many African countries triggered by the war in Ukraine, and the security crisis impacting cargo vessels on the high seas. This new African unity lends additional weight to the continent's tax policy interests at the UN, giving them a power long unseen in global economic policy.

Accordingly, the representatives of the Global South approached the negotiations in April with confidence, and formulated their demands in a consistent and well-founded manner. These encompass the following dimensions of international tax policy: various aspects of corporate taxation, combating unfair financial flows, taxing the digital economy, environmental and climate taxes, taxing large fortunes, information sharing and tax transparency matters, and also tax incentives. The first written draft of the terms of reference of the convention was published in early June. It addresses almost all aspects of G77 demands and forms the basis for the next round of negotiations, set for July and August in New York.

Switzerland drifts along with no ambition

The South's offensive places the OECD countries in something of a predicament. On the one hand, of the issues so far negotiated in the OECD and with its related forums, they want to transfer as few as possible to the UN, they themselves being beneficiaries of the reforms made hitherto. It is no secret that this also applies to Switzerland. Currently, the country is merely drifting along with OECD States in the UN process, with relatively little ambition. At the start of the process, the State Secretariat for International Finance (SIF) was still hoping not to have to participate at all in the negotiations, as the process was deemed a farce. This was clearly a miscalculation. If the OECD group attempts to hinder the UN process by holding fast to the OECD as the authoritative forum for global tax matters, it would further antagonise the countries of the South at the multilateral level. In the light of the current major geopolitical conflicts with Russia and China, "the West" can really no longer afford this. Ultimately, no-one has an interest in seeing Africa, the largest continent, move into the geopolitical camp of Russia and China.

In the UN tax negotiations, the OECD countries are therefore hiding behind what they consider the panacea: "capacity building". They assert their readiness to provide the tax authorities in the Global South with more expertise and money to enable them to catch their tax evaders. In conference room 3, Everlyn Muendo of the Tax Justice Network Africa (TJNA) had a fitting response to this: "We cannot capacity build our way out of the imbalance of taxing rights between developed and developing countries and out of unfair international tax systems." Unlike the OECD, the UN also allows civil society to attend and speak during the negotiations.

It is not a lack of expertise and technical capacity that is costing the Global South tax revenues, but the international tax system itself and the unfair apportionment of taxation rights between North and South that is inherent in that system. The Africa Group and its allies cannot be expected, any time soon, to content themselves with a negotiation outcome that does not offer the prospect of fundamental changes to the international tax system.

The contribution of Alliance Sud expert Dominik Gross to the negotiations in New York at the end of April:

Share post now

global

The Alliance Sud magazine analyses and comments on Switzerland's foreign and development policies. "global" is published four times a year (in german and french) and can be subscribed to free of charge.

Article

Sustainable Finance: a generational project

06.12.2023, Climate justice, Finance and tax policy

In 2015, governments committed to aligning financial flows with the climate objectives of the Paris Agreement. Where do things stand with implementation? What is Switzerland doing? A stocktake.

The financial sector's commitment to climate protection is very contradictory.

© Adeel Halim / Land Rover Our Panet

Signing the Paris Agreement in 2015 the international community committed to significantly reducing greenhouse gas emissions, aiding developing countries in climate change mitigation and adaptation, and directing both public and private finances into a low-carbon economy and climate-resilient development. Article 2.1(c) of the Paris Agreement embodies this goal. The jargon therefore speaks of "Paris alignment".

On 3 and 4 October, government officials, business leaders and representatives from NGOs came together at the 3rd Building Bridges Summit for a two-day workshop in Geneva to explore this orientation and its alignment with Article 9 of the Paris Agreement. This was done with a view to the first "global stocktake" to be conducted at COP28. Under Article 9, developed countries pledged to extend financial support to developing nations for climate change mitigation and adaptation measures. Numerous delegates and NGOs in Geneva have raised concerns that industrialised countries are emphasising private finance alignment while disregarding their commitment to assisting developing countries.

Financial flows for economic activities based on fossil fuels continue to far surpass those meant for mitigation and adaptation measures. The most recent IPCC synthesis report affirms that sufficient capital exists globally to close the worldwide climate investment gaps. The predicament is therefore not a shortage of capital, but rather the ongoing mismanagement and misallocation of funds that is impacting both public and private capital flows. Nevertheless, redirecting financing and investment towards climate action, primarily in the neediest and most vulnerable nations, is no silver bullet. The challenges of a "just transition" go much further, and developing countries also expect financial support from the North.

Responsibility of governments

Businesses, including those in the financial sector, are not bound by the Paris Agreement. Governments therefore have a responsibility to translate climate change commitments into national legislation. Put simply, "Paris alignment" requires governments to ensure that all financial flows contribute to achieving the climate goals of the Paris Agreement. Implementing Article 2.1(c) will require a variety of instruments, and it is primarily up to individual governments to identify the regulatory frameworks, measures, levers and incentives needed to achieve alignment. This will require concrete steps leading to tangible and measurable results for individual companies and financial institutions.

What is Switzerland doing?

By ratifying the Paris Agreement, Switzerland has also committed to making its financial flows compatible with climate goals. The Federal Council is also working with the industry to ensure that the financial centre plays a leading role with regard to sustainable finance. However, it is still relying primarily on voluntary measures and self-regulation.

With the Climate and Innovation Act, the Swiss electorate decided, in June 2023, that Switzerland should achieve climate neutrality by 2050. Interim greenhouse gas reduction targets have been set, along with precise benchmarks for certain sectors (construction, transport and industry). Broadly speaking, all companies must have reduced their emissions to net zero by 2050 at the latest. With specific reference to the goal of aligning financial flows with climate goals, Article 9 of the Climate Act stipulates that: "The Confederation shall ensure that the Swiss financial centre contributes effectively to low-carbon, climate-resilient development. This includes measures to reduce the climate impact of national and international financial flows. To this end, the Federal Council may conclude agreements with the financial sector aimed at aligning financial flows with climate objectives".

The role and responsibility of Switzerland as a financial centre

The facts are clear: the Swiss financial centre is the country's most important "climate lever". The CO2 emissions associated with Switzerland's financial flows (investments in the form of shares, bonds and loans) are 14 to 18 times greater than the emissions produced in Switzerland! It would therefore be logical for the Federal Council to give priority to these financial flows. Given its size – around CHF 7800 billion in assets under management – the Swiss financial centre could make a significant contribution to achieving the climate goals. However, this would require effective measures here at home to help redirect financial flows. This would include credible CO2 pricing, both domestically and – as yet unimplemented – internationally.

Range of measures for Swiss companies and financial market players

From January 2024, large companies – including banks and insurers – will be required to publish a report on climate matters covering not only the financial risks a company faces from its climate-related activities, but also the impact of its business activities on the climate ("double materiality"). The report must also include companies’ transition plans and, "where possible and appropriate", CO2 emission reduction targets that are comparable to Switzerland's climate targets. Like the UK and a number of other countries, the European Union has introduced similar obligations. Thus, for once, Switzerland is not lagging behind.

PACTA Climate Test

Starting in 2017, the Federal Council has recommended that all financial market players – banks, insurers, pension funds and asset managers – should voluntarily participate in the "PACTA Climate Test" every two years. The aim is to analyse the extent to which their investments are in line with the temperature target set by the Paris Agreement. The test covers the equity and bond portfolios of listed companies and the mortgage portfolios of financial institutions. The PACTA is designed to show the portfolio weight of companies operating in the eight most carbon-intensive industries, which account for more than 75 per cent of global CO2 emissions (oil, gas, electricity, automobiles, cement, aviation and steel).

However, participation in the PACTA test remains voluntary and participants are free to choose the portfolios they wish to submit. Furthermore, the publication of individual test results is not (even) mandatory for financial institutions that have set themselves a net-zero target for 2050. The Federal Council recommends rejecting a motion calling for improvements to these aspects, arguing that existing decisions are already sufficient.

Self-declared net-zero targets

Many Swiss financial institutions have voluntarily set themselves carbon-neutral targets under the auspices of the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ). The Federal Council supports this approach. However, these initiatives raise crucial questions about transparency and credibility. What is the percentage of financial institutions that have set net-zero targets? What is the percentage of assets and business activities that will actually be net zero by 2050? How comparable is the information, i.e., final and interim targets and progress made by financial institutions? To increase the transparency and accountability of financial actors, the Federal Council had originally proposed the conclusion of sectoral agreements with them. This was rejected by the financial lobbies. However, the Climate Act now envisages the conclusion of such agreements, and the Federal Department of Finance is to submit a report on the matter by the end of the year.

Swiss Climate Scores

The Swiss Climate Scores (SCS) were developed by the authorities and industry and introduced by the Federal Council in June 2022 in keeping with GFANZ. The basic idea is to create transparency regarding the Paris alignment of financial flows in order to encourage investment decisions that contribute to achieving the global climate goals. Here too, the approach remains voluntary for financial service providers.

At the Building Bridges Summit, the CEO of the asset management firm BlackRock Switzerland lamented the low uptake of the SCS in her industry. This confirmed the misgivings expressed by Alliance Sud when they were introduced. The daily newspaper NZZ also recently noted the low uptake and inconsistencies in implementation by financial institutions – describing the SCS as a "refrigerator label" for financial products compared to the EU's sophisticated regulatory framework.

Paradigm shift

Implementing Article 2.1(c) of the Paris Agreement will therefore also be a major undertaking for Switzerland. The range of largely voluntary measures adopted so far clearly falls short of the Paris commitments. A paradigm shift is therefore urgently needed.

The Federal Council recently proposed the adoption of a motion calling for the creation of a "co-regulation mechanism" and a commitment that this mechanism would become binding "if, by 2028, less than 80 per cent of the financial flows of Swiss institutions are on track to achieve the greenhouse gas reductions envisaged in the Paris Agreement".

It is now up to the parliament to take the first steps to tackle this generational project.

Share post now

Reportage

Rooms with a view

06.12.2023, Finance and tax policy