Share post now

global

The Alliance Sud magazine analyses and comments on Switzerland's foreign and development policies. "global" is published four times a year (in german and french) and can be subscribed to free of charge.

Article, Global

05.12.2022, International cooperation

Power inequalities are still a major problem in development cooperation. Change is under way where decolonization is seriously being promoted.

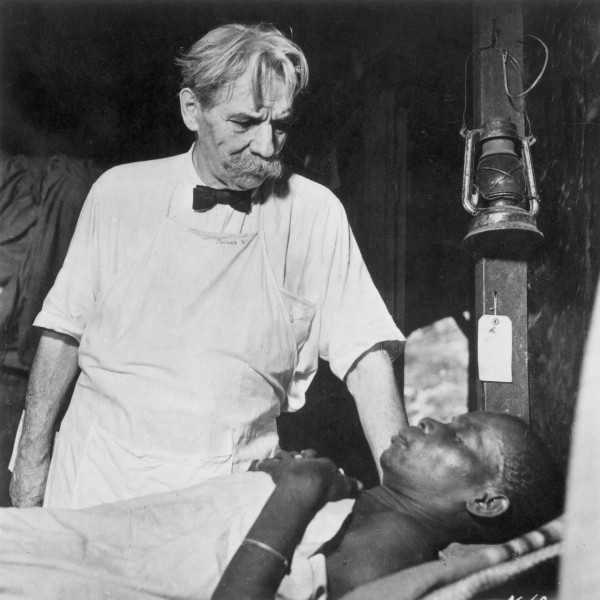

Doctor, philosopher, theologian, organist, Nobel Peace Prize winner - and a "white saviour"? Albert Schweitzer (1875 - 1965) in Lambarene, Gabon.

© The Granger Collection, New York / Keystone

Development cooperation (DC) has changed radically over the past 30 years. However, despite progress on many fronts, many people still retain a very colonial image and understanding of development aid: on one side there are mostly dark-skinned, poverty-stricken people, seemingly incapable of lifting themselves out of poverty on their own; and on the other, overwhelmingly white, altruistic helpers, who are using their knowledge and expertise as best they can to help the poor.

Correcting this (self) perception and shifting the power to define and make decisions about development from the North to the South is at the heart of discussions on the decolonization of aid, which have gained considerable momentum in recent years. Launched by humanitarian organizations in the Global South, the debate is now also taking place in academia and has long found a place in the work of many international non-governmental organizations (NGOs).

This article highlights three aspects that are pivotal to a new, decolonized understanding of development aid: the historical and political contextualisation of development cooperation, a complete revision of the images and narratives that are being conveyed by development actors, as well as the ongoing evolution of the modalities of cooperation.

In an address to the nation in 1949, US President Truman spoke for the first time of rich, "developed" nations having to use their progress to assist poor "underdeveloped" countries with their development. Poorer countries – with the assistance from the richer nations – needed to create the general political and economic framework conditions, which would bring them closer to the living standard of the latter. Whereas Truman's primary motive at the time was to curb the rise of communism in poorer countries, European colonial powers also embraced the concept of development aid, as it allowed them to preserve their influence in the now independent colonies, while burying the horrors of the colonial era behind a smokescreen of altruistic aid.

From the very beginning, development policy frameworks propagated by the West were designed to preserve Western political influence as well as access to the vital commodities and resources of poorer nations. This so-called development aid furthermore often had conditions attached to it in order to secure markets for Western companies in poorer countries – a practice that has come to be known as "tied aid".

As of the 1960s, the Western-dominated global financial institutions (World Bank and IMF) also played a key role in the realm of global economic policy. After many of the newly independent governments contracted massive debts with the World Bank and the IMF in the 1960s and 70s, most often to build major (generally export-oriented) infrastructure projects, new lending in the 1980s was tied to strict conditions regarding market and trade liberalization and a roll-back of the state. While these so-called structural adjustment programmes (SAPs) promoted global economic liberalization, poverty and hunger increased exponentially in most of the "structurally adjusted" countries. In parallel, numerous NGOs emerged and took over the work of States weakened by the SAPs, for example in the areas of education, health or water and sanitation (WASH).

It was only in the 1990s that an initial phase of self-reflection in the development sector took shape – on the back of massive civil society protests against World Bank and IMF policies, as well as increasing internal and external criticism of the top-down agenda of the development industry and its failure to alleviate poverty. From then on, more attention started to be paid to topics such as human rights, governance and political context analysis and measurable poverty reduction was now given a central place. Furthermore, the issues of coordination among donor countries, as well as the increased cooperation with various players in the Global South (ranging from governments to civil society organizations) started to gain relevance. As a result of these deliberations, at least officially, the term “development aid” was replaced by “development cooperation”.

While the practice of "tied aid" is frowned upon in development cooperation today much more emphasis is being placed on human rights and the rule of law, and the principle of “cooperation” has become more important, the colonial image of the "white saviours" still persists. This image also stems from the conviction that development is something linear and that we in Western industrialized countries have achieved an ideal state of development thanks to efficiency, intelligence and innovation. Forgotten are slavery, imperialism and colonialism, as well as unfair global trade and economic relations, which are still in place today and without which Western prosperity would not exist in its present form.

Whether knowingly or not, today's development cooperation still continues to reinforce an outdated image of development through its communication and fundraising activities – an image inspired by stereotypes of poverty, white saviours and a lack of contextualization. Even the language used in development cooperation can reinforce these images – for example, the frequently used term "capacity building" implies a lack of knowledge and capacity on the part of local people and organizations. In a recently published open letter, 93 Ukrainian organizations and more than 100 individuals sent a clear message and a challenge to international organizations and NGOs: Stop speaking on our behalf, and stop spinning narratives in such a way that they promote your own institutional interests! The member organizations of Alliance Sud and other NGOs have recognized this problem and have jointly launched a manifesto for responsible communication in development cooperation.

Besides the urgently needed revision of the images and narratives being disseminated by development actors, the modalities of cooperation between Western donors and local recipients are also eliciting criticism in the current decolonization debate. Civil society organizations from the Global South, who are doing crucial work in numerous fields – from protecting human rights and combating poverty to environmental protection and the fight against corruption – feel sidelined in present-day development cooperation. They denounce the fact that decisions are made mostly in the West, that they often act as mere implementing partners for projects decided by Western development actors, who do not trust them and that their local knowledge is hardly ever valued.

The fact is that international development is still dominated by Western "experts" and that there are huge disparities not only in the salaries of expats and local collaborators, but also in their powers of decision-making and action. Furthermore, an OECD study published in 2019 shows that only about one per cent of overall bilateral development funding directly went to local organizations in developing countries. The study also shows that civil society organizations are used preferably as implementing partners for donor-country projects and priorities and are seldom regarded as autonomous development actors in their own right. Access to funding, especially for small, local organizations, is being massively hampered by complex bureaucratic procedures and requirements and competition from larger international organisations.

The debate around the decolonization of aid is crucial, in that it demonstrates that development cooperation is not free of outdated colonial thought patterns and behaviours. However, it is also important to avoid generalizations in this debate. The history of the World Bank and the IMF is different from that of the UN, of bilateral development cooperation, or of NGOs. And while development cooperation as a whole may still fall far short of a fully decolonized, partnership-based cooperation, much has changed for the better in recent years. Human rights and democratization have become more important, the localization and decolonization of development aid are now being seriously discussed and promoted at various levels. Several NGOs, for example, hire mainly local staff in their offices abroad or work exclusively with local organizations, in keeping with the principle "locally led and globally connected". Besides, the work of many international organizations and NGOs has become more political: global injustices are being denounced and tackled jointly with NGOs in the South.

It is also important to always situate development cooperation in an overall context. While many policy areas still effectively facilitate the transfer of resources and value creation from the Global South to the Global North, as well as the exportation of unwanted waste back to the South, development cooperation constitutes one of the few policy areas in which funds) can flow back from the North to the South in a manner more or less devoid of self-interest (depending on the country and institution) and in which global problems can be jointly tackled.

For the future of development cooperation, it is now important to ensure that words are followed by deeds, that existing patterns of funding, knowledge generation and cooperation are broken in order to truly share decision-making power and make room for non-Western ways of thinking and acting: only in this way will true cooperation among equals become possible. Furthermore, a clear, new narrative must be constructed – shifting away from "aid" towards Western responsibility and compensation, away from "developed" countries and countries "to be developed", from "helpers" and "beneficiaries" towards shared global learning and development processes that work towards global sustainability and justice.

Many of the problems currently facing poorer countries originate in the Global North: unsustainable commodity extraction that involves human rights abuses, tax avoidance, illegitimate and unlawful financial flows, or the worsening climate crisis are but a few examples. Now more than ever, tackling the root causes of these problems will require cross-border networking and cooperation on the basis of partnership.

Share post now

global

The Alliance Sud magazine analyses and comments on Switzerland's foreign and development policies. "global" is published four times a year (in german and french) and can be subscribed to free of charge.